Kevin Frazier will join the Crump College of Law at St. Thomas University as an Assistant Professor starting this Fall. He currently is a clerk on the Montana Supreme Court.

A republican government rests on a critical assumption: that the public’s virtuous traits and, in particular, the virtues of elected officials will outweigh the “degree of depravity” in humankind. In other words, virtue is at the heart of a representative government--at least according to Federalist Paper No. 55.

The Founders did not shy away from discussing virtue and politics in the same breath. They assumed that the people would elect virtuous officials and, in the event that a dishonest, immoral, or corrupt official took office, political leaders in the Revolutionary Era developed checks to ease the removal of such officials. Pennsylvanians and Vermonters, for example, created Councils of Censors that assessed whether the legislative and executive branches of government performed their duty as guardians of the people. Violations of such duties could result in censure and impeachment.

At some point the public stopped assuming politicians possessed any more virtue than everyone else. People today perceive politics as a realm where mudslinging goes further than deliberating, where the perfectibility of humankind loses out to the possibility of greater power in the hands of fewer individuals, and where those most willing to sacrifice their morals will have the easiest time of getting ahead. Two-thirds of Americans say that the statement "most politicians are corrupt" describes the U.S. well, according to a 2020 Pew Research Center poll. The perception of corruption has had a corrosive effect on our democracy.

The absence of virtue in the political arena is a major problem. The devolution of politics into a WWE wrestling match makes it easier for opponents of any law to question the intentions of the law’s proponents and, therefore, the legitimacy of the law and our system of government as a whole. Consider that the same 2020 Pew poll that revealed the public’s concerns with corruption also exposed the public’s increased willingness to drastically reform our system of government. More than two-thirds of Americans agreed that the U.S. political system required "major" changes and a sizable group—about a fifth—asserted that our political system should undergo a complete reformation.

Thankfully, the Council of Censors of the past provide the present with a model for how to provide a check on corrupt politicians. The Pennsylvania Council of Censors included 24 citizens who had been elected from districts around the state. Councilors served single, seven year terms. As mentioned, the Council could censure public officials and order impeachments, in addition to possessing the authority to recommend the repeal of legislation, and if required, call for a Constitutional convention.

A modern improvement of this Council would eliminate the election of Councilors and instead rely on a stratified random sample to select a representative body of the public to evaluate the behavior of their officials. Selection by a sort of lottery process would reduce the odds of partisan bias influencing Council decisions and provide the Council with more legitimacy on the basis of having a wide range of views and backgrounds on the Council. Whether a modern Council should have the same powers as those in Pennsylvania and Vermont is a question for another article. At a minimum, the Council should evaluate if elected officials veer too far from the public’s perception of virtue.

Opposition to morality mixing with governance is understandable. After all, who gets to choose which morals serve as the standard for assessing what qualifies as “good” political behavior? Some may understandably fear that a focus on refining the character of citizens and improving their virtue will open the door to undue influence by religious thinking. Others may argue that a focus on morals and virtue will further pull the country into culture wars that limit our ability to wage battle on more pressing fronts such as income inequality, climate change, and distrust in democratic institutions. This is another reason why a random sample of everyday citizens is the best approach - diverse Councilors would encapsulate the values and morals of the entire community.

Virtue has a place in our politics. Ethical leadership should not be hard to come by in D.C. nor in any state capitol. The modern adoption of Councils of Censors could revive an assumption of the past: that politics can and will bring out the best in our community.

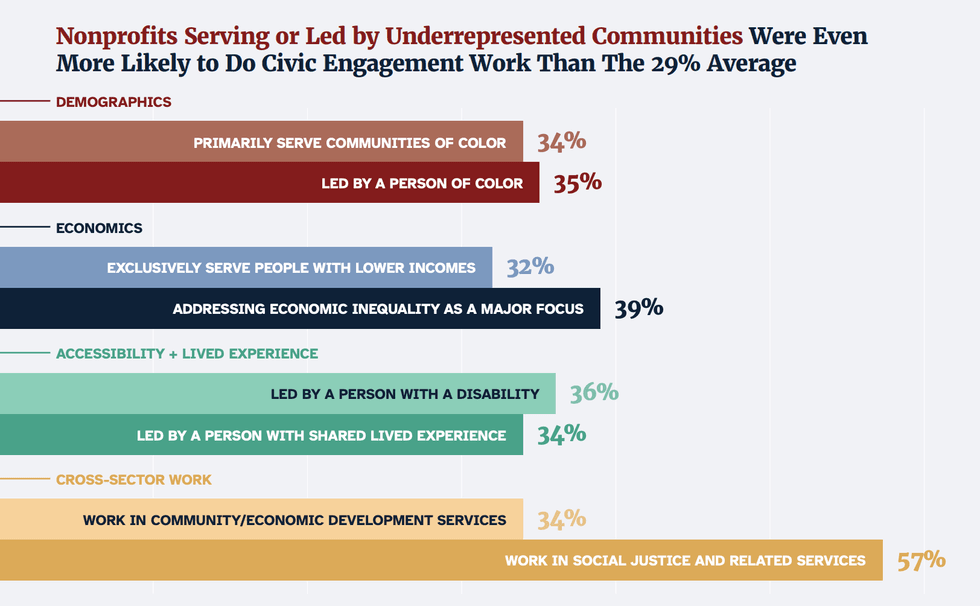

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift