After one wild and crazy election season, evening has fallen on an Election Day that seems to have been refreshingly normal. That was the general sense for how things were going at polling places across the country, with only a few hours to go Tuesday.

There were sporadic and isolated problems but nothing close to widespread technological glitches. And the most notable effort to suppress voting — misleading robocalls in several states that the FBI was investigating — may have been the most alarming thing keeping election officials and independent monitors on their toes.

But, with a few hours to go, one of the most divisive and complex tests ever for American electoral democracy seemed to be nearing the end with unexpected calm. And very long lines of people waiting to do their civic duty.

"We were bracing for the worst and have been pleasantly surprised," Kristen Clarke of the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, which ran the largest election monitoring operation in the country, said in the early evening.

More than 101 million people had voted ahead of Election Day — almost two-thirds of them by mail, with several million more such absentee ballots expected to get delivered on time to be counted.

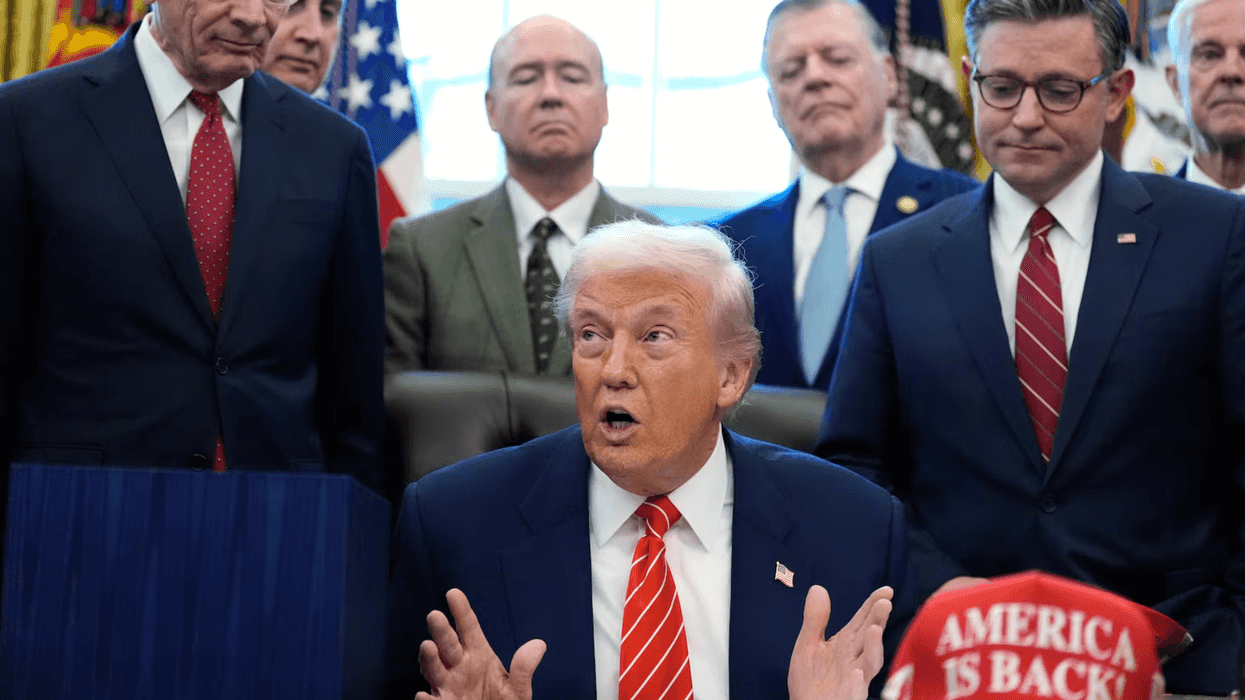

President Trump has relentlessly cast doubt on the security of the election, focusing mainly on mail-in ballots. His campaign organized an army of 50,000 volunteers to monitor day-of voting in Democratic-leaning areas. But there had been essentially no verifiable reports of voter intimidation.

In D.C., federal Judge Emmet Sullivan ordered the Postal Service to conduct a sweep of a dozen Postal Service processing facilities during the afternoon to "ensure that no ballots have been held up" in regions that have been slow to process mail ballots. He ordered the inspections after the agency said about 300,000 ballots seemed essentially missing in transit.

But at the end of the afternoon, USPS essentially said it had ignored the judge's order in favor of sticking with its own quality control schedule.

At the same time, a wave of suspicious robocalls and texts began bombarding telephones in much of the country soon after the polls opened, their unclear origin raising suspicions of last-minute foreign interference. Millions of them urged people to "stay safe and stay home" on Election Day. Another wave of automated calls in Flint, the sixth largest city in battleground Michigan, told people to vote tomorrow if they hoped to avoid long lines today.

That is not possible, of course, leaving officials scrambling to reassure voters of the rules. Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan pledged to "work quickly to stamp out misinformation." The FBI was investigating the larger wave of calls.

The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, one of the many voting rights groups that has battled all year to make voting easier despite the coronavirus pandemic, detailed the range of complaints to its hotline. The presidential battlegrounds of Pennsylvania, Florida, Michigan and Texas had produced the most calls — along with reliably blue New York.

Thirty phone banks of volunteer attorneys across the country had fielded 30,000 calls by the evening, still a relatively high call volume reflecting the elecortrate's anxieties. The top complaints were about challenged registrations, potential voter intimidation and polling site access.

Clarke said the most concerning incident stemmed from plagued electronic poll books in two rural counties near Atlanta. Voters were being asked to use paper ballots, but those soon ran out at several locations.

Clarke initially labeled the situation a "crisis-level issue" in tossup Georgia and said her group was considering suing to force an extension of voting hours. But later in the day she said the situation had been largely resolved.

In Philadelphia, two precincts did not open their polls before the afternoon.

Concerns about excessively long waiting times at the polls, historically a sign of voter suppression in many parts of the Unites States, were reported at numerous locations around the country in the morning — but those lines eased after the vote-as-soon-as-possible rush ended.

One likely reason for that is the record-setting number of people who voted by mail or in person in advance — leaving perhaps only 50 million ballots to be cast Tuesday, or one-third the total cast four years ago.

Two incidents of voter intimidation were reported in Florida. In one, five pickup trucks were blocking the entrance to a parking lot at a polling place in Orange County, where Orlando is located. In the other, two men who said they were with law enforcement, but were not in uniform, were seated outside a polling place in Tampa and were questioning voters as they entered.

In Ohio, voting machines malfunctioned at several polling sites in Franklin County, where Columbus is located, forcing people to use paper ballots. Other voters were given provisional ballots, which Clarke said was improper.

North Carolina's Board of Elections extended voting at four voting locations in suburban counties near Greensboro, Charlotte and Fayetteville. The board granted extensions as long as 45 minutes — meaning a delay in reporting results statewide until 8:15 p.m.. State law says no returns can be announced until all voting has ended. The extensions were sought because of technical glitches that caused the doors to open late in all four places.

Approximately 50 voters were given an incorrect ballot (it was missing a state House race) when they showed up to vote right when the polls opened at Hickory Ridge Middle School in Harrisburg, outside Charlotte. County officials made arrangements for them to vote for other offices in the morning and come back later to vote for state representative.

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room