Nine months from an intensely contested presidential election already clouded by anxiety about the integrity of the results, the main federal agency overseeing the process is struggling to get back on its feet after years in turmoil.

The Election Assistance Commission is unknown to most Americans. But it certifies the reliability of the machines most voters will use this fall, and it's at the epicenter of efforts to protect our election systems from being hacked by foreign adversaries.

And since last fall it's been without an executive director or general counsel to coordinate the government's limited supervision over how states and thousands of localities plan for the 2020 balloting. In fact, none of eight top officials listed on the agency website in March 2017, when the extent of Russian interference in the last presidential election was just becoming clear, are still with the agency. Neither are eight of the other 16 staff members who worked there then. And years of budget cuts have only recently started to be reversed.

The ability of the already tiny operation to do its job in the leadup to November — when turnout and fear of hacking could both reach record levels — could go a long way to determining whether the world believes President Trump was either defeated or re-elected fair and square.

It is a tall order that will be left largely to the four politically appointed commissioners, and two of them are new since Trump took office. Only a year ago did the EAC gain a full complement of members for the first time in almost a decade.

The agency has had "very real and persistent resources challenges in recent years," Donald Palmer, who joined the commission last January, conceded in congressional testimony last fall. But despite this, he insisted, "the EAC has fulfilled its obligations and even expanded the support it provides to election administrators and voters."

Responding to a series of questions about its challenges, the agency declared in a statement that it is "looking forward, not backward" and is "singularly focused on advancing our mission to serve America's election officials and voters."

As a prime example, it boasted that it took just four weeks to award states the most recent $425 million in election security grants, allocated by Congress only at the end of December.

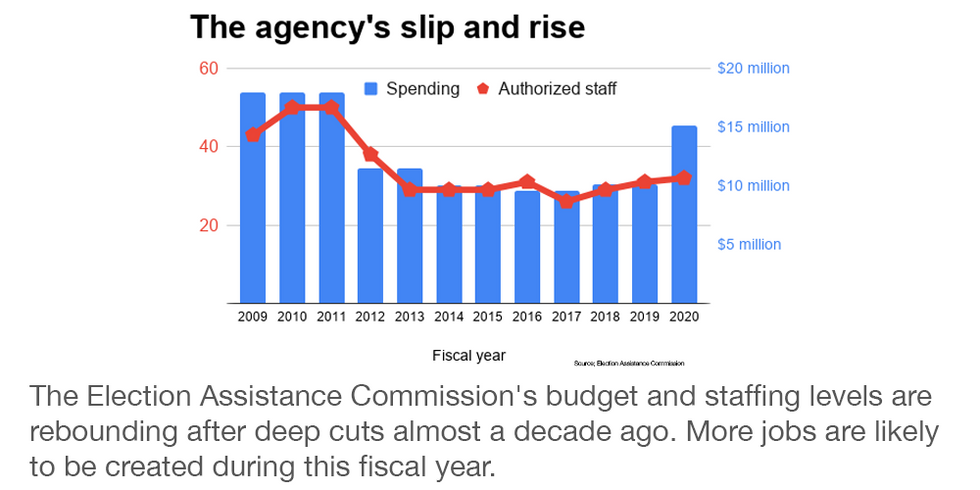

The EAC also received a big percentage boost in its own budget for this year, but at $15.2 million its funding is still less than what it was in 2010. It's also about the same as what taxpayers are spending this year to maintain the greenhouses filled with flowers and plants at the U.S. Botanic Garden at the foot of Capitol Hill.

The number of employees is also less than half of what it was a decade ago — assuring it will remain a tiny organization compared with the outsized task it is given and the potentially historic consequences of falling short.

Last fall, Commissioner Ben Hovland told a House committee the EAC "absolutely does not" have enough money to do its job, noting that Kansas City, Mo., spends more on pothole repair than is allocated to the agency.

"I would note that if we were a Major League Baseball player, we would be the 173rd highest paid player," he said. "We would be a middle reliever." (Even with the recent increase, 81 major leaguers earn more than what the EAC will be allowed to spend this fiscal year.)

Plus, the agency faces several other big tasks in the coming year besides preparing for Election Day.

The commissioners will soon begin considering finalists to be executive director, recently forwarded by a search committee. They are hoping to vote early this year on an updated set of standards for the security and accessibility of voting machines. And their staff will be administering election security grants, which have totaled $800 million in the past two years, that the states can obtain for projects that extend well beyond this November's balloting. Tristiaña Hinton/The Fulcrum

Tristiaña Hinton/The Fulcrum

Budget cuts and mismanagement

How the Election Assistance Commission came to be in such a precarious position at such a critical time is about even more than the usual mix of budgetary cutbacks, political gridlock, partisan backlash and even efforts to kill the agency. It also involves a highly controversial policy decision by the previous executive director and revelations of an inappropriate affair.

The agency was created in 2002, two years after the closest and most hotly disputed presidential contest in modern American history, when Congress set the first nationwide standards for the conduct of elections and formed the EAC mainly to provide oversight and administer federal aid.

Its fortunes started suffering at the end of the decade, after the country emerged from the Great Recession and Washinton started looking for ways to reduce the huge deficits created by all the federal spending to spur the recovery.

The Obama administration proposed and Congress enacted deep cuts starting in 2012. In the next five years the agency shrank by half, from 50 full-time positions and a $19 million budget down to 26 jobs and $9.6 million. Republicans pushed legislation for several years to eliminate the EAC altogether, arguing it was no longer necessary and the Federal Election Commission could take over its duties.

The problems for the former executive director, Brian Newby, began just a few months after he took the job. Without the commission's approval, he went against agency policy in early 2016 and gave the OK to three states — Kansas, Georgia and Alabama — to include a request for proof of citizenship on the voter registration applications handed out at motor vehicle offices and other state agencies.

That prompted the League of Women Voters and others to sue. A federal judge blocked use of the forms while the commission decided if Newby had acted properly. But the panel deadlocked. While the two Republican appointees backed him, three votes were required. (The Democrat disagreed and the fourth seat was vacant at the time.)

Democrats' anger at Newby was further stoked when emails obtained by the Associated Press revealed he was having an affair with a woman whom he supervised while in his previous job as the top election official in Johnson County, the most populous county in Kansas.

On top of that, an audit of the office found Newby and the woman made purchases that did not have business justification and proper documentation. Both of them were also accused of verbally abusing employees in the office.

During an EAC oversight hearing by the House Administration Committee in May, Rep. Marcia Fudge made an oblique reference to Newby's behavior while in Kansas and the action that led to the lawsuit. Anytime people are paid with tax dollars they need to be held to the highest standards, the Ohio Democrat said, her frustration and anger evident, and "I clearly don't think that is the case here."

For her part, Democratic Chairwoman Zoe Lofgren of California said that "serious personnel mismanagement and occasional hyper-partisanship by executive leadership at the commission has too often distracted from their mission."

Gridlock and partisanship

So it was not surprising, when it came time last fall to vote on extending Newby's employment, that the two Democratic commissioners voted no while the two Republicans voted yes. The tie meant his time at the EAC was over.

The same partisan deadlock also ended the tenure of Cliff Tatum as general counsel. In that case, it was only the Republicans who went public in wanting him gone on the grounds of poor performance.

There was no public notice of the voting, which apparently was done by email rather than the usual public meeting. The result and commissioners' reasons for their votes were posted on the agency website.

In a lengthy statement about the vote, GOP Commissioner Christy McCormick said it was the wrong time to "remove the leadership team" during the development of the new voting machine guidance and so close to the presidential election. The Democrats' criticism of Newby "is baseless and unsupported by any evidence and is purely political and partisan," she wrote, and his work "has turned the agency around from near death."

On the other hand, McCormick wrote Tatum's job performance has "been lacking." "He has not provided requested timely written legal advice on matters," she wrote, and added that he had not conducted the review of EAC policy and procedures that had been asked of him more than three years previously.

Besides the executive director and general counsel positions, the EAC is also working to fill seven other jobs including director of communications, human resources specialist and grants specialist. And it recently announced it was reviving the position of chief operating officer, with a salary of up to $156,000.

As for Newby, last month he began as the director of elections for North Dakota.