Dzieduszycka-Suinat is the president of the U.S. Vote Foundation, a nonprofit that works to ensure that all citizens become voters.

Outrage over the new Georgia law is warranted. It's an overt suppression scheme — aimed at Black voters, specifically, and overall turnout, generally. But before we give much more oxygen to the measure's red herring, criminalizing distribution of food and water to people in long lines at the polls, let's highlight its dangerous core: allowing elected officials to manipulate election outcomes.

An authoritarian handbook couldn't have delivered a more effective strategy.

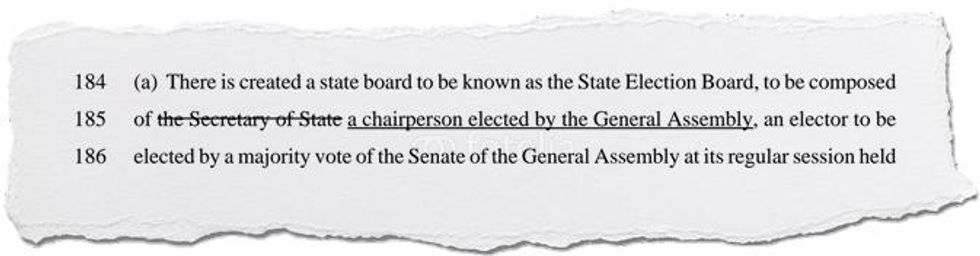

Under the law, ostensibly enacted in response to a "significant lack of confidence in Georgia election systems," the secretary of state is no longer chair of the State Election Board; that statewide elected official will be replaced by a "chairperson elected by the General Assembly." The board issues regulations governing elections, investigates fraud allegations and — significantly — it sets the rules on "what constitutes a vote and what will be counted as a vote."

Courtesy U.S. Vote Foundation

Courtesy U.S. Vote Foundation

The Republican-majority legislature was no doubt inspired to write this section by Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger's failure to reconsider the 2020 presidential election's outcome — despite intense pressure to do so from a fellow Republican, the defeated President Donald Trump.

But there's more. Going forward, the state board may "suspend county or municipal superintendents" and appoint new people to temporarily act in their places.

Counties in Georgia, as in most states, hold great power; they register voters, maintain voter lists, conduct all of the ballot casting and then certify elections. Appoint someone who is too biased to take charge of a county election office, and suddenly the fox is guarding the hen house. Registration purges become heavy-handed, applications are put "on hold," recounts take place on shaky ground. And all these actions affect outcomes, potentially shifting the result of a close race.

Supporters of Georgia's new statute may say: "Look, don't worry, because the law restricts the state board from suspending any more than four county supervisors." But in the last election, seven of the 10 counties that swung the most heavily toward the Democrats in the entire country (compared with 2016) were in metro Atlanta. And President Biden carried five of them on his way to turning the state blue on the national map for the first time since 1992.

So, permission to control the elections in a majority of the state's pivotal counties means the GOP-dominated board will be close to controlling the whole election. The choice of four counties was no accident.

Indeed, no provision in the Georgia law looks to be more harmful to Black voters, and their historic 2020 turnout, or more fatal to democracy's survival.

Voter suppression in Georgia already relies on a bevy of tools to shape outcomes before they occur: strict ID laws, voter registration purges, shuttered polling places, partisan gerrymandering and unrestricted campaign contributions, to name only the most prominent.

If those tactics fail and the results in the ballot boxes still don't favor the suppressors — in Georgia or anywhere else — they have some back-end solutions, too: baseless lawsuits challenging the outcomes, calls from the powerful pressuring for "do-overs" and, as of Jan. 6, even a violent insurrection in the very seat of government.

After the last election, the evidence-free lawsuits didn't work, the calls for outcome flips went unheeded and the Capitol remained intact. So, when all else failed, it was time for the losers to start rewriting the rules.

This latest tactic is especially powerful. Whereas strict ID requirements — and other blatantly racist measures — often backfire by driving record numbers to the polls, some other laws force voters to question whether the process itself is legitimate and so whether they should bother participating.

Why show up when the system is stacked against you? When your ballot could get tossed on a political whim? Cultivating that skepticism and subsequent apathy is exactly what Georgian lawmakers had in mind. A citizen who feels powerless is a non-voter. And that's the most effective way to suppress the vote.

Tactics like this are used the world over. Like the Georgia lawmakers asserting "election integrity" concerns as their motive, military commanders in Myanmar asserted "voter fraud" as their justification in February for overturning an election and taking power.

To be sure, that democracy was relatively fresh and the people had already lived through military rule. But when there are breakdowns like the one in Georgia — when parts of the country become "laboratories of authoritarianism" rather than experiments in democracy — they potentially create a domino effect across the land.

Our centuries-old form of government will not necessarily die in one fell swoop. Its demise, like going broke, could happen slowly, slowly, then all at once.

But we can avoid a dangerous trajectory by passing a strong counter-measure: legislation to revive the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which for almost half a century helped protect Black voters and other minority citizens from discriminatory election laws. A bill in Congress would update the system, struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013 as unconstitutionally outdated, requiring places with discriminatory voting rules to get federal permission before altering any election regulations.

Enacting the measure would mean states and counties would be judged not by their historic sins but by their current actions and intentions. Some states have shown they need the help.

Federal legislative fixes are essential, but they won't solve the problem alone. Lawmakers must be reminded that tables turn, and manipulative rules like those now on the books in Georgia can come back to haunt them.

And when that happens, parties don't just implode. Democracy as a whole self-combusts.