Schmitt is director of the political reform program at New America, a nonpartisan think tank.

A presidential campaign is a contest of ideas, not just personalities. As candidates set out policy priorities and develop proposals, we learn more about what they care about, but we also see in their reflection what voters and party activists want to hear. The proposals that even the failed candidates embrace, and the priority they give them, can foreshadow ideas that will take hold in the future.

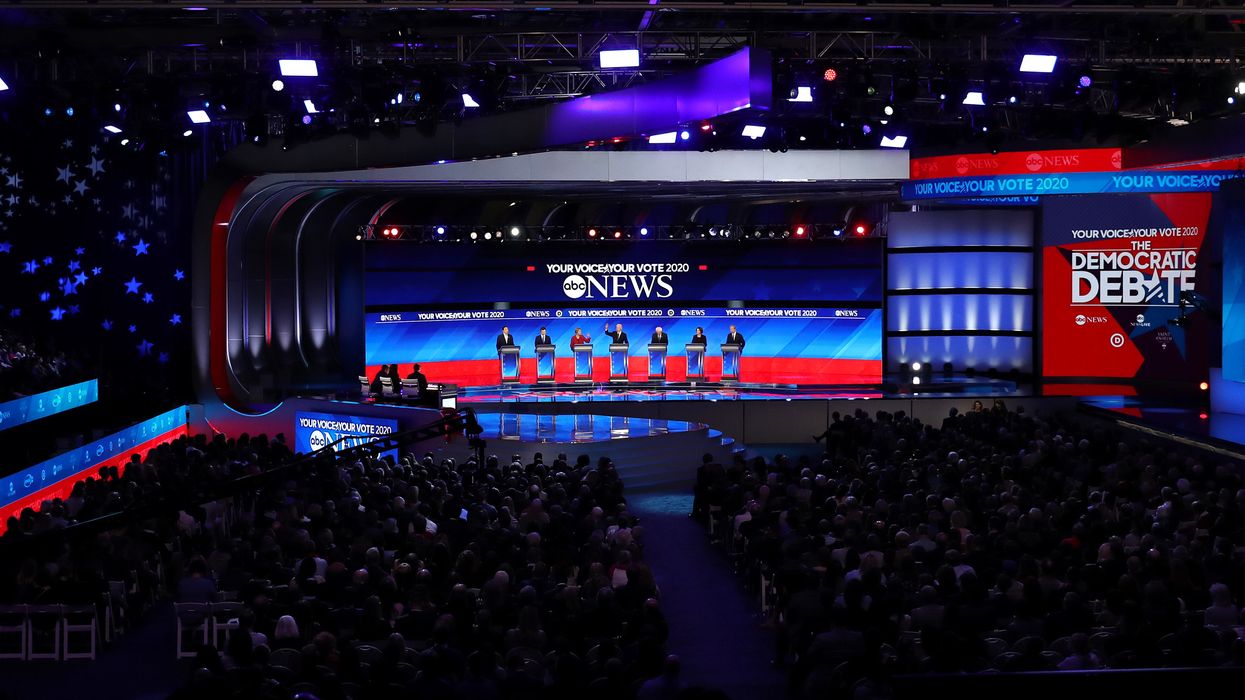

New America looked into how the major candidates for president have been talking about reform of democracy. We took an inventory of the ideas emerging in this high-intensity laboratory. What we found validated our colleague Lee Drutman's recent observation that "from the long arc of American political history, I see the bright flashing arrows of a new age of reform and renewal ahead."

Not since 1976, after Watergate and an earlier impeachment, has the vision of reforming democracy itself been as central to a presidential contest as it is now.

While curbing the influence of money in politics has been on the agenda in previous campaigns — it was central to 2008 Republican nominee John McCain's career, and Barack Obama emphasized restrictions on lobbying — the range of different democracy reform issues on the agenda this year is unprecedented. In the decade since the Citizens United v. FEC and Shelby County v. Holder decisions, citizens have been mobilized by concerns about voting rights, corruption and the relationship between economic and political power.

President Trump has embraced some limits on the "revolving door" between lobbying and government, but he has appointed more lobbyists to key positions in three years than his two predecessors did in eight. Otherwise, Trump has not endorsed any elements of a political reform agenda, and promotes removing voters from the rolls.

His only remaining Republican challenger, William Weld, the former Massachusetts governor and Libertarian vice presidential nominee in 2016, has challenged the winner-take-all allocation of electoral votes and embraced ranked-choice voting.

Republican presidential candidate Bill Weld, campaigning in New Hampshire, has embraced ranked-choice voting.Scott Eisen/Getty Images

Republican presidential candidate Bill Weld, campaigning in New Hampshire, has embraced ranked-choice voting.Scott Eisen/Getty Images

The Democratic candidates' positions on democracy can be grouped in three categories. One involves expanding voting rights, reinstating provisions of the Voting Rights Act, ending voter ID and felon disenfranchisement laws and otherwise extending the promise of democracy. A second focuses on corruption, limiting the influence of lobbyists and regulating campaign donations. Last are changing three institutions to make it easier for a majority to achieve lasting policy changes and overcome the barriers to majoritarian government: the Electoral College, the Senate filibuster and the Supreme Court.

In the first category, a candidate who has left the race, Cory Booker, was the pacesetter in advocating expanded voting rights, automatic voter registration, voting by mail and making Election Day a holiday. Pete Buttigieg has similarly proposed a "21st Century Voting Rights Act," which would "use every resource of the federal government to end voter suppression." Others, embrace automatic voter registration and reviving more robust oversight of elections in places with discriminatory histories.

A related stream of reform in this category would fix the failures of our winner-take-all system of voting. The most prominent alternative is ranked-choice voting. Several candidates have said they're "open" to such reforms. Bernie Sanders, Michael Bennet and Andrew Yang have been more explicit in endorsing RCV.

Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have approached political reform almost entirely in the second category — promising to end a system that's "rigged" for the wealthy. Warren, unsurprisingly, has the most specific plans to end corruption. She would ban campaign contributions by lobbyists and institute lifetime lobby bans on former elected officials from lobbying. While that could raise constitutional questions and deter people from public service, it directly targets the intersection of money and influence.

Amending the Constitution to reverse both Citizens United and the 1974 Buckley v. Valeo rulings, in order to permit broader regulation of political spending, has consensus support among Democrats. Sanders, Warren, Bennett and Amy Klobuchar all voted for such an amendment in 2014. Most also support a system of public financing based on matching small contributions, though some are vague about its design. Michael Bloomberg takes credit for expanding New York City's model small-donor matching program.

The third category is where the newest and most controversial ideas are found. Particularly during the Obama era, when the Senate blocked most of his initiatives after his first year, Democrats became alarmed by the parts of the system that stymie progress, even when a majority favors change. That alarm remains, with the legislative filibuster the most immediate obstacle. Tom Steyer, Andrew Yang and Warren support ending it. Joe Biden, who was a senator for 36 years, opposes the change. Others are more ambivalent about it.

The Supreme Court also has the power to reverse policies that are popular, leading Buttigieg, Steyer and Yang to embrace changes such as expanding the court or imposing term limits. After the Electoral College vote determined a winner of the 2000 and 2016 elections different from the popular vote, there is new interest in eliminating or reforming that institution as well. Six candidates have expressed support for amending the Constitution or employing an interstate agreement to effectively guarantee the presidency to the winner of the popular vote.

The scope of political reform has expanded well beyond the narrow focus just a few years ago on limiting the power of money in politics and lobbying. But while previous efforts had broad support in both parties, enthusiasm for reform is now concentrated among Democratic candidates and voters.

While this divide is concerning, as is the partisan polarization across so many issues, the crisis of democracy and the hunger for real change makes it plausible the ideas on the agenda this year will capture the imagination of voters and politicians across the political spectrum in the decade ahead.