For those who view the restoration of cross-partisan friendships as genuinely key to making democracy work better, there was a glimmer of hope at the very end of the latest presidential debate.

Each of the Democratic candidates was asked Tuesday night to speak about a friendship that would be a surprise, and nine of the dozen talked exclusively about bonding with Republicans.

The downside, however, is that only two of them mentioned Senate GOP colleagues who will still be in public life after the next election.

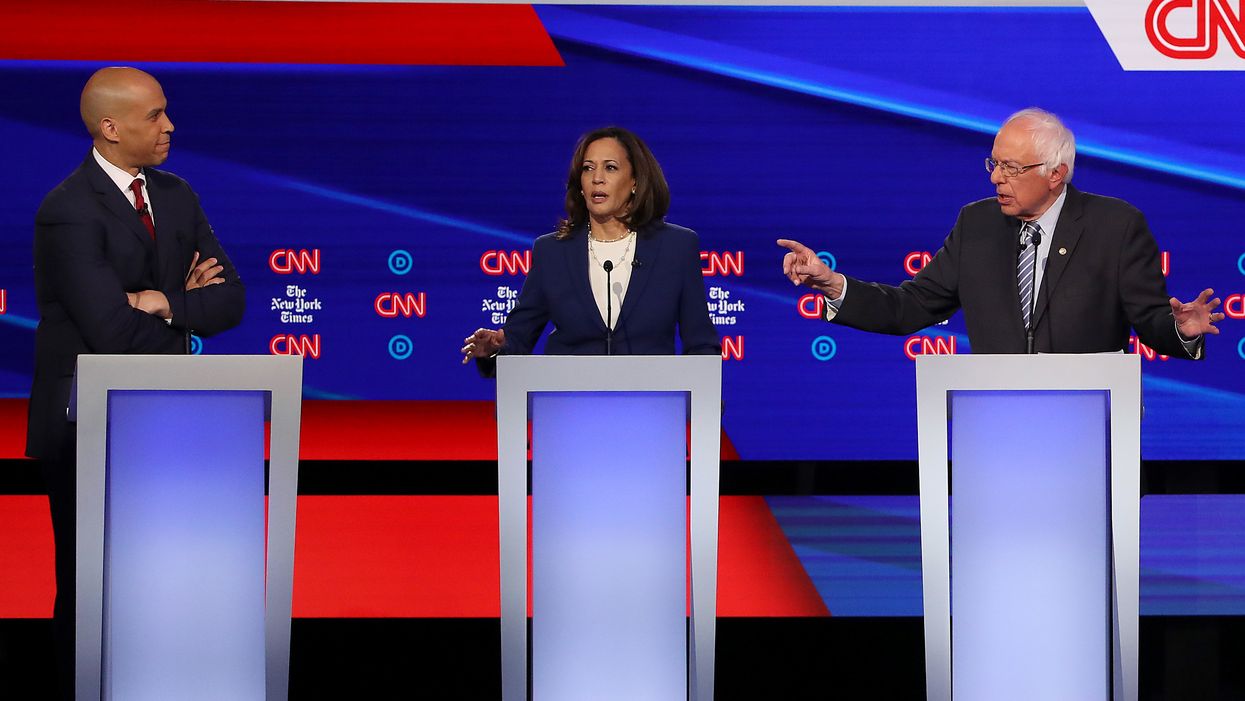

Kamala Harris gave a shout-out to Rand Paul of Kentucky, her partner on legislation to reduce excessive bail for criminal defendants. And Cory Booker singled out a fresh companionship with Ted Cruz of Texas while talking up the benefits of his efforts to have dinner with every Republican senator, also mentioning attending Bible study and working on legislation to improve foster care with Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma.

Time and again, congressional veterans and students of the Capitol Hill culture volunteer that the slide into legislative gridlock, punctuated by polarizing rhetoric, has accelerated thanks to the steep decline in such bipartisan bonding — borne of a combination of tribal-style demands for partisan loyalty and scheduling pressures that stress fundraising far more than connecting with colleagues.

"This is reassuring in the fact that we've all acknowledging that we have to reach across the aisle, to get things done. No other way to get anything done in this country," said former Vice President Joe Biden, recapping his rivals' GOP-heavy roster while crisply encapsulated the core rationale of his own candidacy.

And yet Biden, the last of the candidates to name an unlikely friend, was in the majority naming somebody who is no longer available for collaboration.

He chose the late John McCain, the maverick Republican from Arizona who was one of Biden's most frequent bipartisan collaborators when both were in the Senate. And so did two other senators: Bernie Sanders, who worked with McCain to write an overhaul of veterans health care policy, and Amy Klobuchar, who joined him on several fact-finding trips to global hot spots.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren volunteered Charles Fried, the solicitor general in the second half of the Reagan administration, who later helped her get a teaching job. Rep. Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii went with former Rep. Trey Gowdy of South Carolina, who in recent days was briefly considered for a spot on President Trump's impeachment legal team. Former Rep. Beto O'Rourke talked about the companionship and trust forged during a cross-country road trip ( livestreamed on Facebook) with colleague Will Hurd of Texas, but he's leaving Congress at the end of next year.

The final question of the debate — inspired by the recent online dustup about the personal bond between talk show host Ellen DeGeneres and former President George W. Bush — prompted other candidates into different tacks: Andrew Yang rhapsodized about a conservative trucker named Fred, Pete Buttigieg talked about the people he met in the military from different walks of life, Tom Steyer referenced a conservative environmentalist in South Carolina and Julian Castro spoke fondly of his childhood teachers.

"While we have had major debates about policy, we have to remember that what unites us is so much bigger than what divides us," said Klobuchar, who's also sought to propel herself into the top tier of candidates by positioning herself as a repairer of the partisan breech. "We have to remember that our job is to not just to change policy, but to change the tone in our politics, to look up from our phones, to look at each other, to start talking to each other."

For those worried about democracy's challenges, the discussion was a slightly heartening coda after almost three hours in which the candidates once again gave the issue only minimal attention.

Several of them tangentially lamented the corrupting influence of corporate political donations on policy-making. But only Warren, who now stands with Biden as a polling front-runner, confronted the issue more or less head on — seizing an opening to tout her just-released campaign finance plan, in which she promised to reject big-dollar donations and corporate funders through the general election if she is the nominee and challenged her rivals to disclose who's helping them raise money.

More transparency about these so-called bundlers is a top goal of "good government" groups, but so far their efforts to pressure the 2020 candidates to disclose the identities of their helpers has been largely ignored.

Warren also reiterated her desire to end the minority party's ability to filibuster legislation in the Senate, knowing that attaining 60 votes for any Democratic president's agenda will be extremely difficult in 2021. Her Senate colleagues in the presidential field have been less emphatic about making such a radical change to the way the chamber has operated for more than a century, and some democracy reformers are wary that such a change — already instituted for all confirmations — would drain the last vestiges of bipartisanship from Capitol Hill.

Several of the candidates rehearsed their ideas for Supreme Court changes — term limits, rotating seats or adding additional seats in hopes of making it less polarized (or at least less conservative) — as part of their answer to questions about the future of abortion rights.

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room