Messinger is the founder of Digital Citizen, a media engagement nonprofit that connects Americans to their leaders, each other, and the world.

At summer's end, families buy school supplies and young people hit the town on warm nights. On just such a weekend, the nation was again shattered by mass shootings: this time in Dayton, Ohio, and El Paso. The media coverage, complete with pundits debating gun regulations and mental illness, kicked in immediately. Even President Trump said a few healing words.

What was missing was the voice of the public. What was missing was a place where we Americans, when troubled and saddened, could go to safely connect to each other and our leaders, a place where we might discuss how to solve this horrific problem.

What we need is to accommodate people when they want to engage in spontaneous dialogue, where they already are, to discuss what they want to talk about. At these wrenching moments, citizens should not be relegated to listening to the experts.

The lack of such a place is ironic, because what a friend calls the "healthy democracy movement" — which aims to bring the public voice into the political discourse — has never been stronger. There are more than 250 organizations involved in the #ListenFirst Coalition and more than 100 organizations within the Bridge Alliance umbrella group. All support expanding civil dialogue to "upgrade our democratic republic ... [by] engaging citizens in the political process ... and promoting respectful, civil discourse."

So what has gone wrong? What is keeping citizen voices out of the most urgent debates of today?

I suggest the community of dialogue practitioners can give people a new way to talk to each other.

I am president of Digital Citizen, which has produced more than 20 broadcast and online projects since 1998 featuring citizens in key roles. We're familiar with how people engage through many different platforms and applications. We recognize the healthy democracy movement is still missing a "key app" allowing people to find each other in moments of crisis, such as in the aftermath of mass violence.

Our community has never been closer to accomplishing this, but there's still a serious challenge in the practices and funding structure of our movement. Also, the movement needs to take civil dialogue to scale. Allowing millions of people to engage in productive discussions with people different from themselves is the best way to create lasting change. The lack of these fundamental tools is an unintended consequence of policies that can, in fact, be changed.

A process for welcoming drop-ins, and guiding them to productive discussions on topics in the news, generally does not exist. In fact, the overwhelming majority of dialogues now are the opposite. Created as funding is available, or when a pre-scheduled event is taking place, the topic must be decided well ahead of time.

Worse, participants must be recruited by the organizers, also well in advance. Those who enjoy engaging in dialogues are often over-represented among the recruits. And liberals are more interested in speaking to the "other side," as a general rule, than conservatives. This either skews the pool leftward or forces the recruiter to work very hard to find an ideologically representative group.

To find full engagement, the people themselves need to decide to connect. And this is exactly what is still missing: a place where each can go to talk about the issue we want to talk about, when we want to talk about it. It is difficult to do this in person today, since most communities are now so "red" or so "blue" that the minority side may not feel empowered to speak candidly. So these conversations will need to be online. (That said, a few valiant libraries are becoming physical places where democracy is finding a place to sit down.)

The Internet provides the freedom to leap physical barriers and is uniquely suited to the task.

There are websites that do parts of this already, and could one day become The Place to Go. Living Room Conversations has a brilliant methodology for self-facilitating discussions and uses videoconferencing to connect people. The National Conversation Project gives visitors a choice of topics and then directs them to in-person meet-ups at a nearby physical space on that topic.

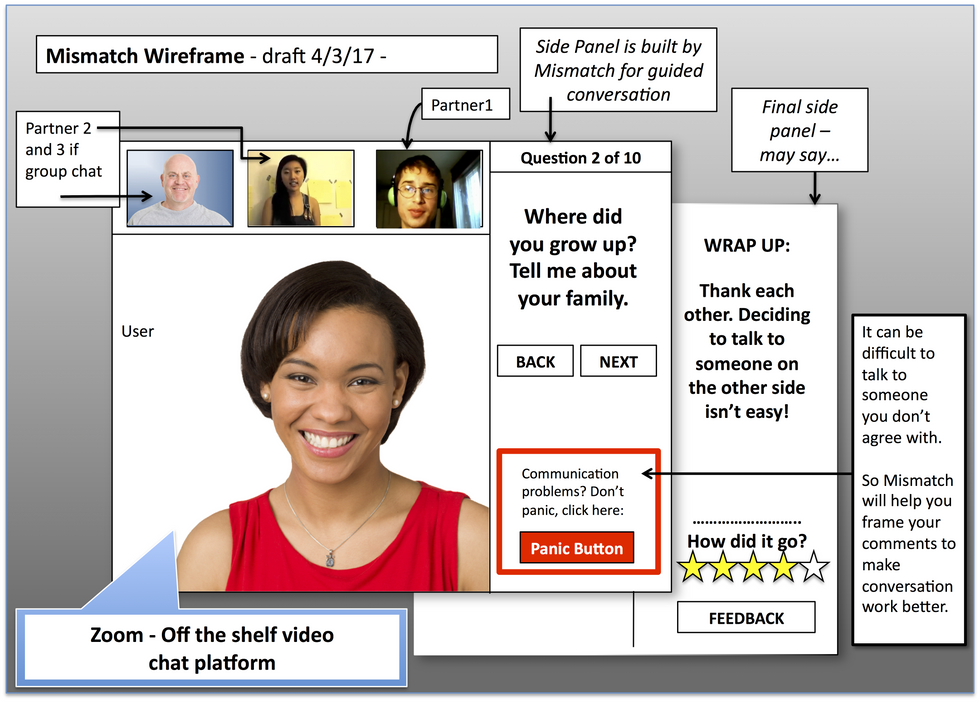

The most promising site, though, is Mismatch. Now focused on schoolroom use, it has been piloted in 20 U.S. classrooms, with more than 300 students participating. Mismatch is working on building an app "like a dating site" in reverse, matching people with those of opposing views, and "guiding them through carefully structured online video conversations."

An example of what the Mismatch app may look like. Digital Citizen

An example of what the Mismatch app may look like. Digital Citizen

So how would a public app work? People would need to know the place exists and it must always be open. When news breaks, it must be able to handle a sudden influx of visitors.

Visitors would state the issue and sign up, then be walked through a demographic and ideological survey. Within a day, they would be introduced to the others in their dialogue group, supplied with well-vetted facts and the rules for civil dialogue, then placed into a video chatv room.

The chatroom will be framed with ample instructions and safeguards.

So what is stopping this? The political climate could not be better for expanding civilized dialogue. New types of funders — especially those in the digital media space seeking a way out of the poisonous present — are already joining traditional funding institutions. The issues of trolls and vitriol may at first seem an impediment, but many tools exist to reduce unwanted intrusion in online discourse. And, unlike when we first began this work, many great organizations can put processes like these in place.

Perhaps a solution is for the Bridge Alliance, and a group of its most powerful members, to commit to making creation of an on-demand, rapid-response dialogue app their joint top priority. So if enough of us tell our funders, the world is ready — and we are ready — it will come.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift