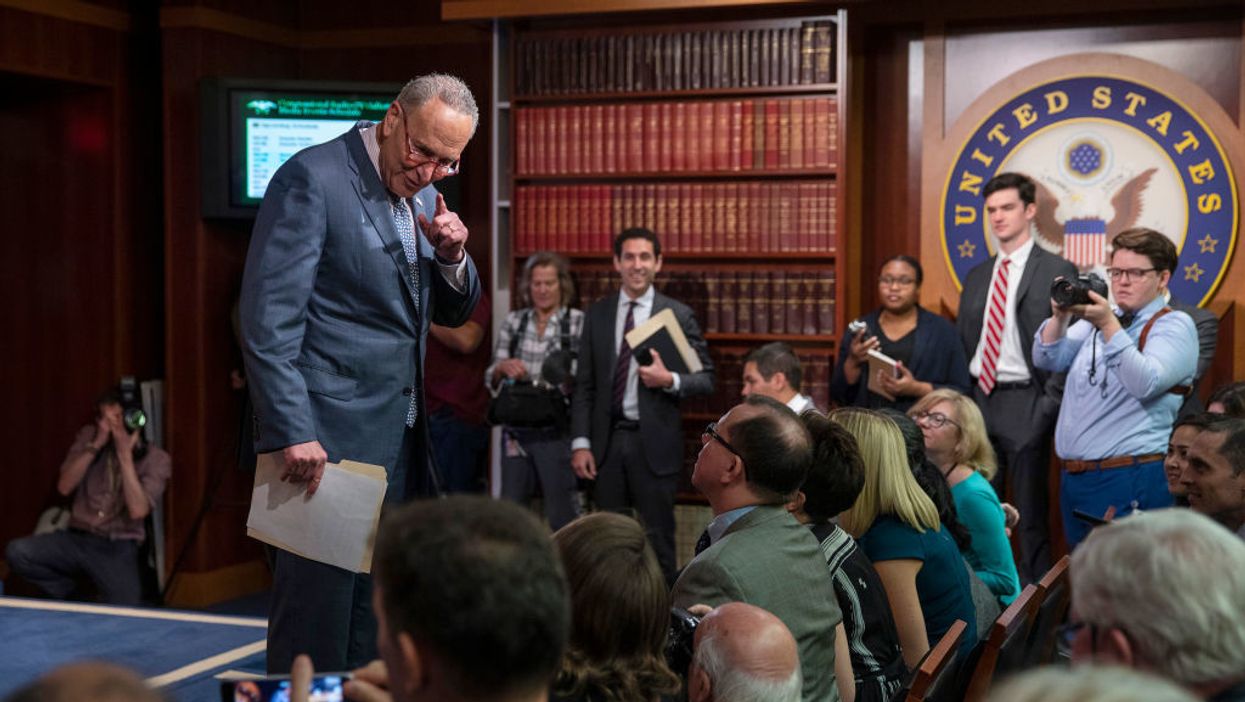

Senatorial shaming is the latest long-shot strategy for advancing legislation designed to secure the American election system against foreign hacking.

Minority Leader Chuck Schumer says he and fellow Democrats will make a show of proposing votes on election security measures on the Senate floor several times in coming days. He's hoping a pivotal bloc of the Republican majority will eventually relent under the pressure, but if nothing else he wants to compel the Republican leader, Mitch McConnell, to openly declare his opposition to legislation designed to prevent a repeat of the aggressive Russian interference in the 2016 election.

"The Republican Senate, Leader McConnell just stands there and twiddles their thumbs and almost says, 'Come on, Putin, let it happen," Schumer told reporters Tuesday, and any lawmaker who rebuffs efforts to protect elections is "abdicating their responsibilities to our grand democracy."

Beneath that rhetoric lies a shaming strategy that Schumer signaled has been resurrected thanks to the recent efforts by, of all people, Jon Stewart. On Capitol Hill last week, the former "Daily Show" host excoriated McConnell for not acting on a bill to secure indefinite federal assistance for ailing Sept. 11 first responders and survivors. The Kentucky senator responded by promising passage of the bill before the current aid fund runs dry.

That example aside, attempts to embarrass McConnell into action have rarely succeeded.

Democrats could not get him to budge from his unprecedented decision to hold a Supreme Court seat vacant for an entire year at the end of Barack Obama's presidency. And their attempts at humiliation have not moved the GOP leader an inch away from his position that the Senate won't act on anything substantive passed along party-lines by the Democratic majority in the House – starting with the package of campaign finance, election and ethics reforms dubbed HR 1.

In essence, McConnell only responds to pressure from within his own caucus. He acts as the tip of the spear for Republican senators' recalcitrance unless a critical mass of them decide they want cooperation instead, and then he transforms into a driven deal-cutter.

"Maybe you can shame people," Alyssa Mastromonaco, a deputy chief of staff in the Obama White House, said on Twitter. "You can't shame McConnell. It would be dope to find a path to greater bipartisanship but this isn't that path."

The next opportunity Schumer has to pressure GOP senators will be during debate on the Pentagon budget bill, one of the only measures enacted without fail every year.

One bill in Schumer's arsenal is clearly designed to land a political punch more than make policy. Written after President Trump declared his readiness to accept information on a campaign opponent from a foreign government, it would legally require presidential campaigns to notify the FBI about any such foreign interference.

But others are more substantive, and sometimes bipartisan. There is growing Republican support, especially in the House, for a measure requiring Internet companies to reveal the purchasers of online political ads. And there's GOP backing for a measure to solidify cybersecurity collaboration and information sharing between federal intelligence agencies and state election administrators.

And there are Republicans, led by Florida's Marco Rubio, promoting legislation setting up tough sanctions if Russia interferes in next year's election.

Beyond all those policy measures, there's bipartisan interest allocating as much as $600 million to replenish a grant program so states and localities can purchase more reliably secure voting equipment in time for November 2020.

The president has signaled no interest in talking about legislation that might suggest his victory was tainted. And McConnell has so far labeled the entire roster of bills duplicative and unnecessary, especially in light of the midterm election. "The missing story that very few of you have written about is the absence of problems in the 2018 election," he told reporters this week. "I think the Trump administration did a much, much better job."

To be sure, the debate over election security measures has become a polarizing matter thanks to the Democrats, as well. Speaker Nancy Pelosi told reporters last week that the House this summer will debate a package of measures written entirely by lawmakers in her party.