A measure that would revamp Alaska's elections will be put to a statewide vote in November.

The package cleared the last remaining hurdle to getting on the ballot Friday, when the state Supreme Court ruled unanimously that it met the requirement that referendums all relate to a single topic.

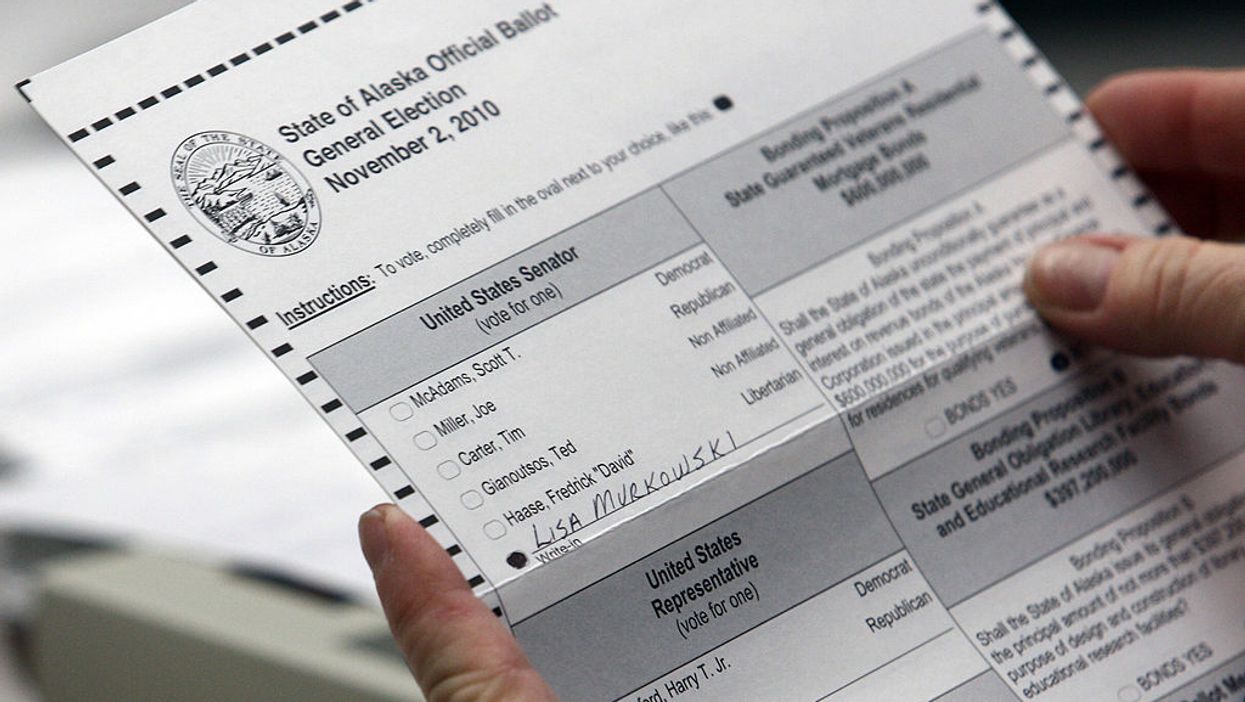

Adoption of the initiative would on a single day push Alaska to the forefront of states adopting central goals of the mainstream democracy reform movement. The proposal would replace traditional partisan primaries for state and federal officeswith single contests open to all candidates; allow the top four finishers to advance to the November ballot; use ranked-choice voting to choose the winner; and bolster state campaign finance rules with strict new disclosure requirements.

While a handful of states have adopted open top-two primary systems, and Florida voters will decide this fall whether to join them, Alaska would be the first with primaries that advance even more candidates to the general election — increasing the likelihood that people who are not Republicans or Democrats will be able to compete in many races.

Maine is now the only state that uses ranked-choice voting statewide, although a November referendum bringing that alternative election system to Massachusetts looks likely.

The path for such a statewide vote in Alaska was cleared after the state's top court decided in favor of Alaskans for Better Elections, the group pushing the referendum, which would not apply to presidential and municipal elections.

Lt. Gov. Kevin Meyer had initially used his unusual power over such matters to refuse to put the proposal on the ballot, arguing it violated a state constitutional requirement that such initiatives be confined to one subject. He was backed in that position by state Attorney General Kevin Clarkson, a fellow Republican.

Meyer argued the proposal was an attempt at logrolling, deliberately combining several dissimilar subjects in order to secure the necessary majority for passage.

The high court, upholding a lower court decision, disagreed. "A plain reading of the initiative shows that its provisions embrace the single subject of 'election reform' and share the nexus of election administration," the justices said.

Importantly, the court also noted the measure showed no transparent attempt to garner voter support through completely unrelated provisions. The court found nothing misleading or unclear about the initiative falling under one broad category of "election reform."

"These two substantive changes are interrelated because they together ensure that voting does not revert to a two-candidate system," Justice Daniel Winfree wrote in explaining why switching to open primaries and the so-called RCV system should be allowed in the same proposal. And while moving away from elections dominated by the two major parties, he said, it's critical for voters to "have adequate and accurate information about who is paying for campaign communications to influence their vote."

Under the proposal, all candidates for governor and other state executive offices, each seat in the Legislature and the three spots in Congress would be listed on one primary ballot. Candidates would have the option to list their party affiliation by their name or be listed "undeclared" or "nonpartisan."

The four with the most votes in the primary, regardless of party affiliation, would be on the general election ballot — at which point the RCV would be used.

Voters would rank their choices and, if no one had a majority of top-choice ballots, an instant runoff would take place. The candidate with the least amount of No. 1 votes would be dropped, and the ballots ranking that person on top would be assigned to the No. 2 candidate — the process repeating until one candidate emerged with majority support.

Voters could still opt to choose only one candidate; ballots that did not rank all the available candidates would not be considered invalid.

After traditional and unchanged presidential primaries, ranked-choice voting would be used to award Alaska's three electoral votes under the referendum. Elections for municipal posts would not be altered.

The final element of the plan would require additional disclosure of contributions to independent expenditure groups and about the sources of contributions in campaigns — generally when the amounts topped $2,000. The proposal would require a disclaimer on paid election communications by independent expenditure groups funded by mostly out-of-state money. Under current federal election campaign law, candidates benefiting from independent expenditures have no reporting obligations.