The mid-decade redistricting fight continues, while the word “hypocrisy” has become increasingly common in the media.

The origin of mid-decade redistricting dates back to the early history of the United States. However, its resurgence and legal acceptance primarily stem from the Texas redistricting effort in 2003, a controversial move by the Republican Party to redraw the state's congressional districts, and the 2006 U.S. Supreme Court decision in League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry. This decision, which confirmed that mid-decade redistricting is not prohibited by federal law, was a significant turning point in the acceptance of this practice.

Then, the Supreme Court case of Rucho v. Common Cause (2019) ruled that claims of partisan gerrymandering are "nonjusticiable political questions." This means there are no issues that the federal courts can or should address. The Rucho case, which involved a challenge to North Carolina's congressional map, opens the door to mid-decade gerrymandering because federal courts cannot intervene; state legislatures, which control the redistricting process, are now less constrained in drawing or redrawing maps mid-decade.

The effort to redraw Texas's congressional districts in the middle of the decade was not initiated by Governor Greg Abbott, as commonly believed. Instead, it was the Republican Party, with President Donald Trump's administration playing a significant role, who pushed for the redrawing of Texas's districts during that time.

Abbot’s signature on the redistricting bill caused the first domino in a growing national redistricting battle to fall.

Given the current judicial landscape, there is little hope that the Supreme Court will intervene to stop states like Texas, California, Missouri, Utah, Ohio, and others from implementing their redistricting laws.

Contrary to popular belief, the practice of gerrymandering, often seen as a partisan tool, has a surprisingly bipartisan history. Both the Democratic and Republican political parties have employed it for many years, dating back to 1812.

Since the 93rd Congress (1973–75), there has been a concerning lack of action on redistricting bills. Despite numerous bills being referred to the appropriate committee or subcommittee, none have taken any substantive action.

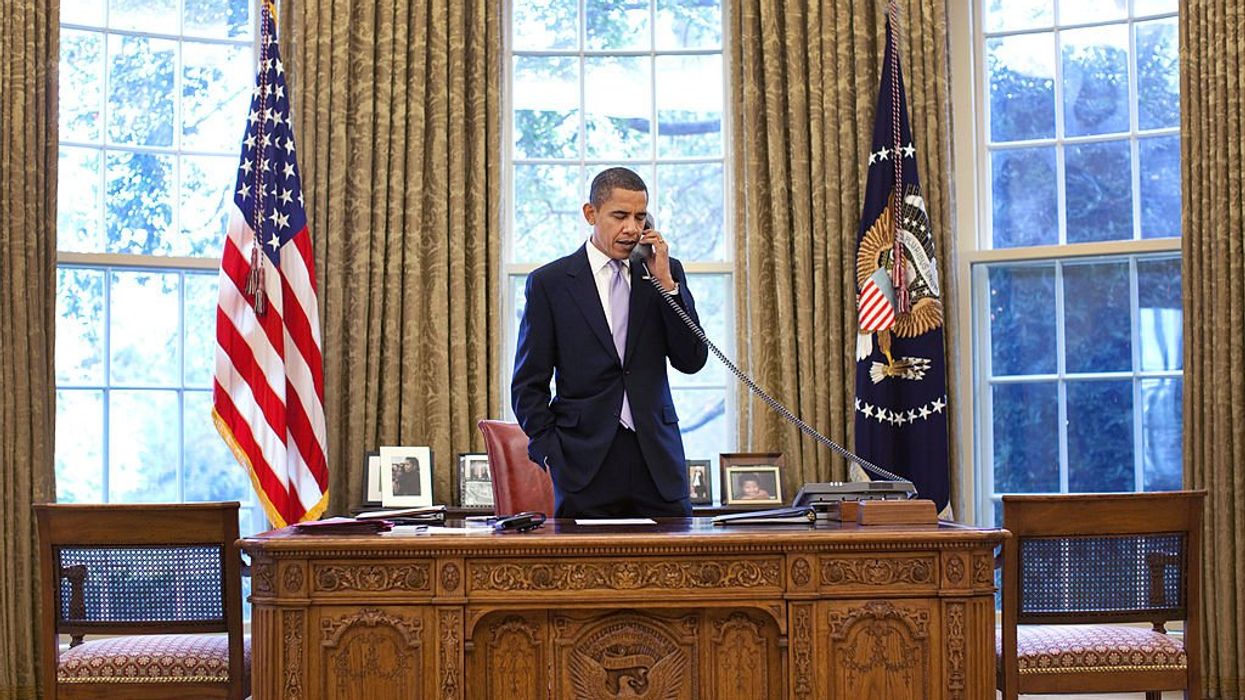

The last political party to control the presidency, the House, and the Senate with a supermajority (60-40) was the Democratic Party during the 111th Congress (2009-10). There were only two periods during this Congress when the Democrats held a 60-seat supermajority in the Senate: from July 7, 2009, to August 25, 2009, and from September 25, 2009, to February 4, 2010. Democratic Barack Obama held the presidency during this Congress.

On June 9, 2021, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) posted on X with the message, “During the Obama administration, folks thought we’d have a 60 Dem majority for a while. It lasted 4 months.”

Does Ocasio-Cortez know that, during the 181 days of the filibuster-proof period, there was no discussion of any election reform bills, such as ending gerrymandering, abolishing the Electoral College, or strengthening voting rights?

During the same period, Obama actively collaborated with Congress to pass the Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), informally referred to as Obamacare. On December 24, 2009, the Senate approved the PPACA with a 60-39 vote, with one member not voting.

However, Democratic Rep. Zoe Lofgren (California) reintroduced her redistricting bill, H.R. 5596, on June 24, 2010, four months after the end of the 60-vote majority. This bill aimed to prevent gerrymandering by allowing each state to establish an independent redistricting commission. It was rejected in committee for the third time because it lacked enough support from Democratic leaders to move forward.

Thanks to this trifecta—a term used in American politics to describe a situation where one party controls the presidency, the House, and the Senate—Obama and his Democratic Party would have been right, since it has long been a tradition in American politics that every 10 years, the party controlling state legislatures (in 2009, the Democratic Party held 61 state legislative chambers) could use gerrymandering to redraw districts in its favor for the next congressional election (2012).

The 2010 midterm elections marked a major turning point in U.S. politics. The Democratic Party’s outlook was the worst of that election cycle, as it lost 63 House seats, six Senate seats, and six governorships. This significant loss of power was primarily caused by the strategic use of gerrymandering by the Republican Party, which utilized the $30 million REDistricting Majority Project (REDMAP) to effect these changes, sparking a Republican wave that gave them control of legislative chambers in swing states.

In his 2016 State of the Union address, Obama told Congress, "We have to end the practice of drawing our congressional districts so that politicians can pick their voters, and not the other way around. Let a bipartisan group do it."

Ironically, after stepping down from his presidential duties in 2017, Obama joined his former attorney general, Eric Holder Jr., in leading the National Democratic Redistricting Committee (NDRC), a key player in the redistricting landscape.

While claiming to oppose partisan gerrymandering, the reality is quite different. Its website describes the NDRC as "the centralized hub for executing a comprehensive redistricting strategy that shifts the redistricting power, creating fair districts where Democrats can compete." Its IRS filings state that the organization's purpose is to "build a comprehensive plan to favorably position Democrats for the redistricting process through 2022."

In 2021, Obama publicly supported the "For the People Act," which includes a provision requiring all states to adopt independent redistricting commissions for drawing congressional district maps. A year later, he endorsed the Freedom to Vote Act and the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, both of which contain provisions establishing federal standards to reduce partisan gerrymandering. There is no widely reported information indicating that Obama specifically lobbied Senators Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) to support these bills. As a result, these Democratic senators voted against lowering the Senate’s 60-vote threshold to pass both bills.

Currently, the NDRC opposes the mid-decade redistricting effort in Texas while supporting the California redistricting ballot measure (Proposition 50) during the same period. These actions raise questions about the NDRC’s mission: to create a fairer redistricting system in the United States and to rebuild a democracy where voters choose their politicians, not the other way around.

After watching the video of Obama’s address to Texas Democrats on August 15, I could tell him, "Obama, you’re 15 years too late!"

Howard Gorrell is an advocate for the deaf, a former Republican Party election statistician, and a longtime congressional aide. He has been advocating against partisan gerrymandering for four decades.