Fisher is deputy director of reforms and partnerships at Unite America, a nonpartisan organization dedicated to "enacting structural political reforms and electing candidates who put people over party."

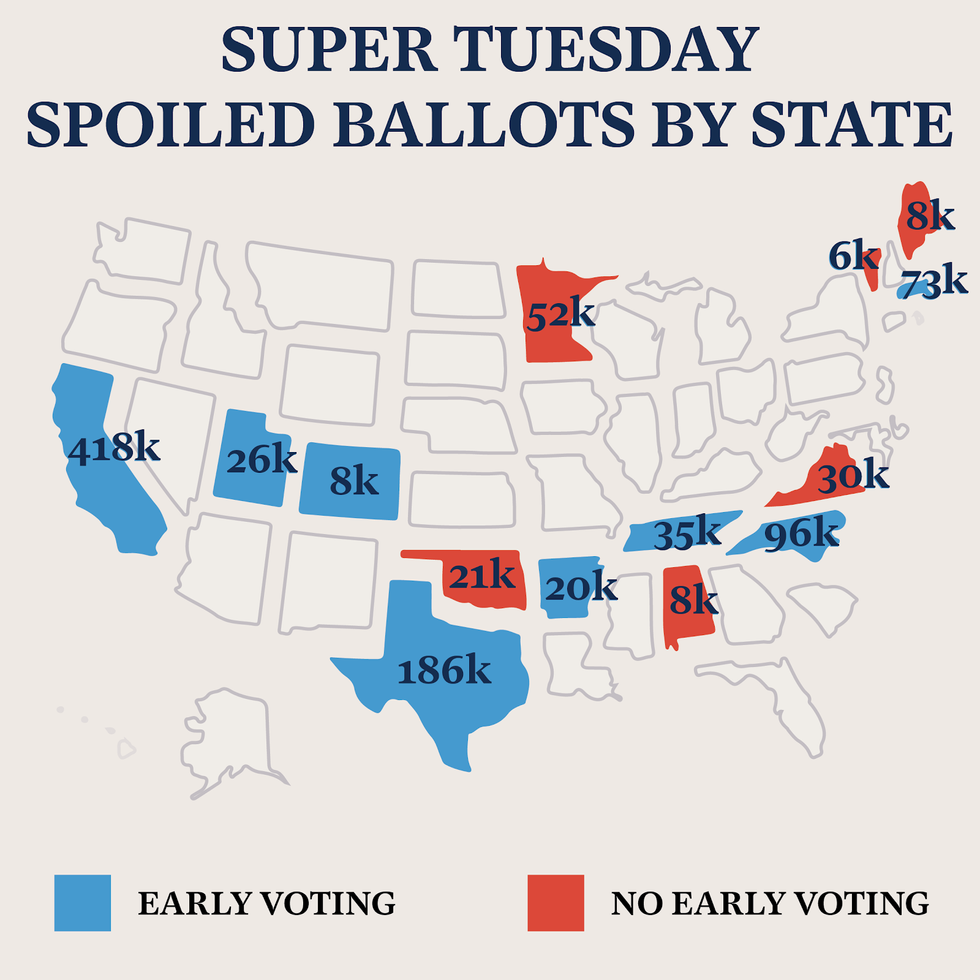

More than 1 million ballots were spoiled on candidates who had already left the presidential race when 14 states voted on Super Tuesday. Three major candidates had ended their bids following the South Carolina primary that was held three days earlier — but early voters and those participating by mail had no way to change their vote in most states.

In-person early voting and vote by mail are common sense reforms that increase voter turnout, especially in primary elections; we encourage these types of reforms that expand the electorate by reducing barriers to participation -- but we can make the system better.

The answer is a simple change to how we vote: ranked-choice voting.

Ranked-choice voting allows voters to rank their candidates in order of preference, from favorite to least favorite. In a presidential primary, if a candidate does not reach the 15 percent viability threshold, voters who cast first place votes for that candidate have their second place vote counted.

Unite America research

Unite America research

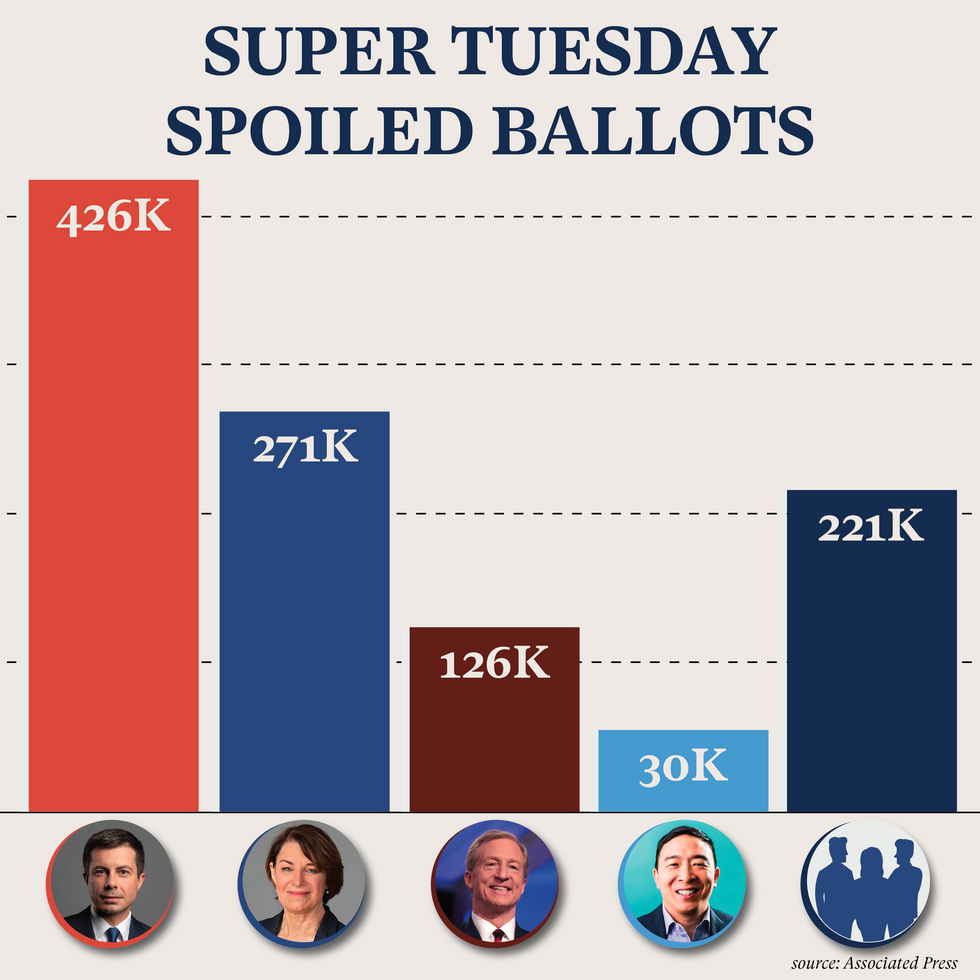

Under the reform, an early-voting supporter of Pete Buttigieg whose second favorite candidate was Joe Biden would have had their vote counted. Likewise, someone casting a vote from home for Amy Klobachar whose second preference was Elizabeth Warren could have had their voice heard after Klobuchar dropped out Monday morning; if Warren did not meet the 15 percent viability threshold on election night, the voter's third choice would have counted.

In the three days between the South Carolina primary and Super Tuesday, Tom Steyer, Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobachar all ended their presidential bids. These candidates alone accounted for over 800,000 wasted votes.

Nevada already successfully used ranked-choice voting in 2020 for voters participating early. Nearly 75,000 voters cast ranked-choice ballots while only 30,000 participated at in-person caucuses. All Democratic primary voters in Alaska, Kansas, Wyoming and Hawaii will use the system.

Unite America research

Unite America research

RCV is not a partisan issue, though. On Tuesday, over 100,000 spoiled votes were cast for former Rep. Joe Walsh, who dropped his primary bid against President Trump weeks ago. In 2016, hundreds of thousands of votes in the Republican primary were similarly spoiled as candidates dropped out of the race.

As states like Massachusetts and Alaska consider joining Maine in conducting their general elections with ranked-choice voting, both the Republican and Democratic parties should consider upgrading their elections to a system that puts voters first by giving them more voice, choice and power in the process.

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room