Daley is a senior fellow at FairVote, a nonpartisan electoral reform organization. Richie is FairVote's president and CEO.

Kansas Democrats wanted to increase participation in their May 2020 presidential contest and make the balloting fairer for everyone. The state's 2016 caucus seemed to go on forever: There were hours upon hours of speeches, followed by the laborious process of dividing into groups for each candidate and being counted one by one. Only then could participants begin often hours-long drives home.

Maine voters sought to protect their state's longstanding tradition of independent candidates and vigorous third parties, while also ensuring that winning candidates had genuine majority support. Nine of the state's last 11 governors, including Democrats, Republicans and independents, and dating back to the 1970s, won with a mere plurality. They wanted to retain all their choices, but also elect the winner with the widest backing.

Eastpointe, Mich., meanwhile, wanted to ensure that black voters elected their fair share of city government seats. The city needed to resolve a Voting Rights Act complaint filed by the Department of Justice that alleged Eastpointe's practice of electing local offices through citywide elections prevented black people – almost one-third of the population -- from winning. No black candidates had been elected to the city council or school board there prior to the DOJ complaint.

New York, the nation's largest city, also had a problem with representative elections. Since 2009, according to Common Cause, two-thirds of all primaries with more than two candidates were won by a candidate with less than 50 percent support. The city's new public advocate captured the office with just a third.

They all hit on the same solution: ranked-choice voting. Now everyone seems to be taking notice. Indeed, at least some voters in at least 25 states are now slated to cast RCV ballots in upcoming elections and primaries.

New York's charter commission just endorsed RCV for all city elections; it will go before voters this fall.

Kansas Democrats aren't the only state party that hit upon RCV as the perfect solution to a time-consuming caucus with as many as 25 Democratic presidential candidates. At least six state Democratic parties plan to use RCV for all or part of their 2020 caucuses or primaries, including for all early voters in Iowa and Nevada, and all voters in Alaska, Hawaii and Wyoming.

These party leaders understand that limiting voters to a single choice poorly accommodates a crowded field of well-qualified candidates because it results in spoilers, vote-splitting and the greater potential of a nominee who lacks majority support inside the party. They had the insight that the best thing about in-person caucuses was the chance for participants to move to a backup candidate who was viable if their first choice couldn't win delegates – and that RCV preserved that greater power for voters.

Those seeking the presidency have figured that out as well. Last month, Sen. Elizabeth Warren signaled her support, suggesting that RCV would both empower voters and encourage greater participation. "Engaging more people and saying, 'OK, talk about your first choice and your second choice,'"she told Vox, "might help us as a country get more people both running for office and engaged in those political campaigns."

William Weld, the former Massachusetts governor waging a Republican primary challenge against President Trump, is also a big fan. Other Democratic presidential candidates backing RCV including Sens. Bernie Sanders and Michael Bennet, Reps. Seth Moulton and Beto O'Rourke and businessman Andrew Yang. It has been backed by Barack Obama and John McCain, by conservative New York Times columnist David Brooks and liberals at The Nation.

Indeed, no electoral reform new to most Americans has more momentum than RCV or more potential to transform our broken politics. After years of steady progress and painstakingly slow removal of election administration barriers to use of ranked choice voting, RCV is on the move. After years of holding the RCV banner, our organization, FairVote, is thrilled by a flood of new civic, political, funder and volunteer allies.

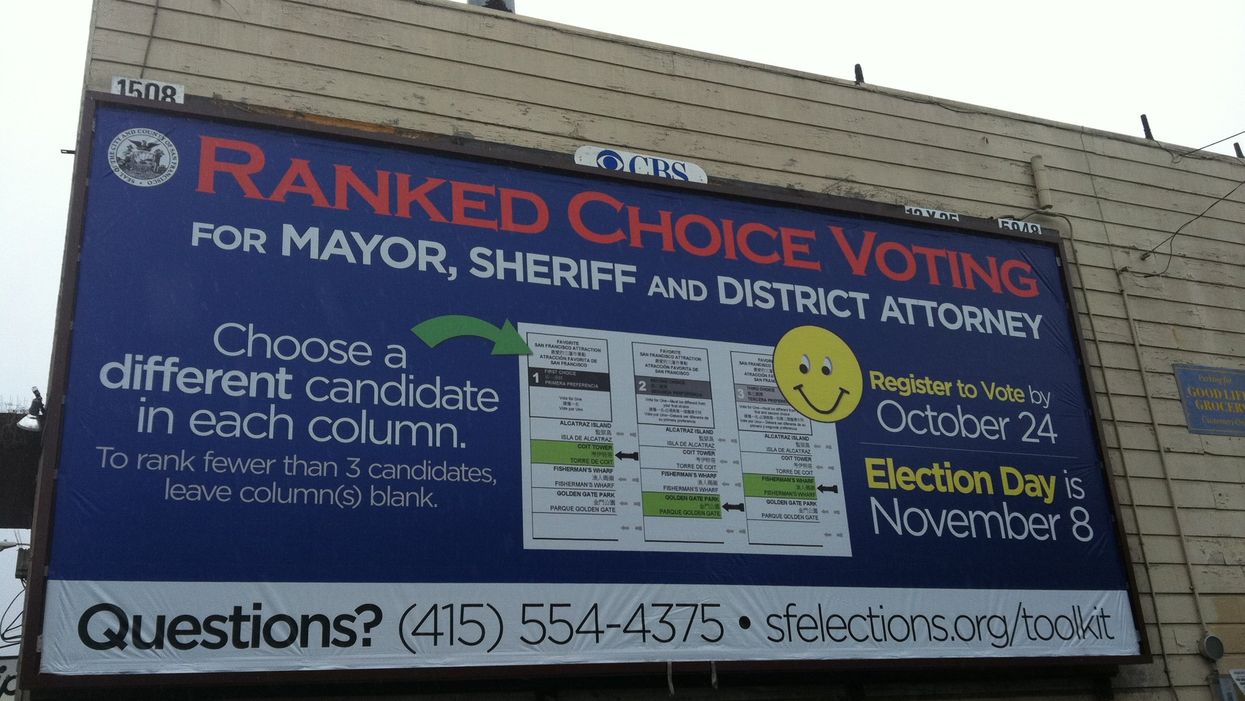

How does it work? RCV is both simple and elegant: A ranked-choice election mimics an instant runoff. A candidate with a majority in the tally of first round votes wins, same as any other race. But if no one wins outright, the last place finisher is eliminated and his or her second-choice votes now count. Rinse and repeat until someone crosses the magical 50 percent plus one threshold. Just like that, a majority winner, with no costly (and low turnout) runoff necessary.

RCV's rising energy can be attributed to the number of electoral problems that it helps solve.

In one-party New York City, RCV helps create majority winners in heavily contested primaries. In Eastpointe, RCV in a multi-seat election allows a majority to win the most seats, but helps everyone else win their fair share as an American form of proportional representation. And in a 25-candidate Democratic primary field, RCV would allow everyone to back the candidate they like the most, without helping the candidate they like least, while determining a nominee that most people could get behind.

The cities and towns nationwide that have become early adopters of RCV, however, have seen even more improvements to their politics. Last year, in San Francisco's mayoral race as well as Maine's Democratic primary for governor, candidates joined forces and made ads seeking second choice support. RCV encouraged a more civil race, and gave candidates incentives to reach beyond their own base and talk to everyone – newly elected Mayor London Breed was ranked highly by more than 60 percent of San Francisco voters in a large field even as more city voters cast a mayoral vote than a vote for governor or senator.

Utah cities hold a nonpartisan August primary to winnow their fields, but only when too many candidates file in May, creating uncertainty and more expensive campaigns. Their state legislature passed a bill and earmarked funding to create an option to allow elections always to be decided in November.

After an overwhelming 13-1 vote of support by its charter commission, New York will have the chance to pass RCV this November and use it in the open-seat race for mayor in 2021. Other states, including Massachusetts and Michigan, are following Maine and proceeding toward ballot measures that would establish it there. Later this summer, a national RCV bill is expected to be introduced before Congress, and other bills with wide support would require all new voting equipment purchased with federal dollars to be ready to run RCV elections.

RCV is also a key part of the Fair Representation Act, Rep. Don Beyer's comprehensive solution to gerrymandering that combines RCV with use of larger districts that are drawn by independent commissions and elect more than one representative. This form of RCV will be used this November in Eastpointe and is under consideration as a remedy in other federal voting rights cases, including for city council races in Lowell, Mass.

The cracks in our political system have become an increasingly serious part of our political conversation. During the 2016 Democratic primary process, there wasn't a single question during any of the presidential debates about gerrymandering. This year, all two dozen candidates have signed a fair districts pledge sponsored by Eric Holder's National Democratic Redistricting Commission.

Holder and many prominent Supreme Court cases have raised redistricting's profile, as have ballot measures in several states. RCV, meanwhile, has come from the people, is entirely nonpartisan, and can't be said to favor any political party. Warren told Vox that it caught her attention because it's "come out of the grassroots," and is a sign of "how much democracy itself is reinventing."

Just as exciting, as soon as voters get a taste of RCV, they want more. Both chambers of Maine's legislature just voted to expand RCV to all presidential contests there – both their primary and their November election for electoral votes. While a procedural snag will delay sending the approved bill to the governor, the bill is still alive for a special session or next year. This is another first in the nation – and another sign that more choice and a greater voice have universal appeal.