Hladick is the policy manager at Unite America, which promotes an array of electoral reforms and helps finance other advocacy organizations, and political candidates, with a commitment to cross-partisanship. (It is a donor to The Fulcrum.)

Unprecedented and unforeseen disruptions to democratic processes — the coronavirus pandemic is only the most recent and profound — require innovative problem-solving. This is especially true of political party conventions, which serve the important role of congregating parties in-person, but are hard to carry out traditionally while practicing social distancing.

Republicans and Democrats in Utah didn't let the spread of Covid-19 delay their conventions at the end of April. Instead, both parties convened their first-ever virtual conventions and then used mobile apps and ranked-choice voting (also referred to as the "instant runoff" system) to award nominations for governor, Congress and state attorney general.

Under Utah's unusual rules, both major parties emphasize a pre-election endorsement process in picking their nominees. Candidates advance directly to the November general election ballot if they receive 60 percent support at a party convention. If no candidate reaches that threshold, the top two face off on the primary ballot. Candidates who choose to forgo the convention process may still get on primary ballots by gathering petition signatures.

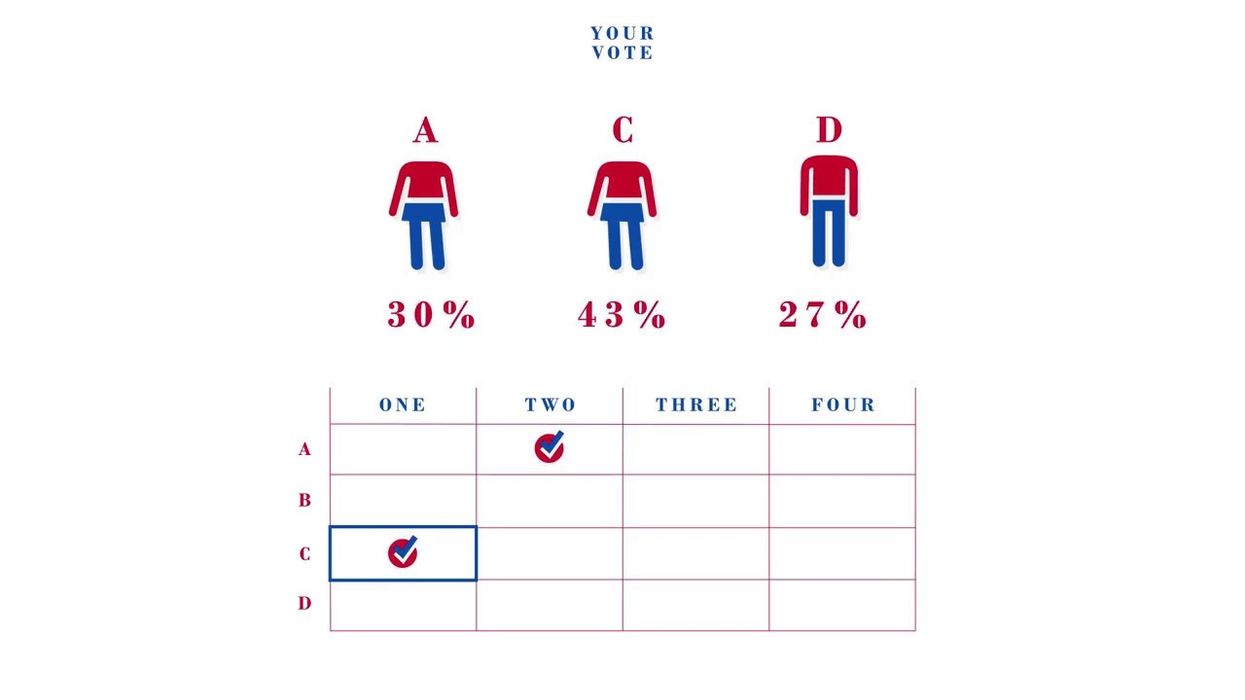

This time, ranked-choice voting meant delegates could rank multiple candidates in order of preference on one ballot. Ballots were counted in rounds. When no candidate was ranked first by three-fifths of the delegates, the least popular candidate was eliminated. Whenever the eliminated candidate was a delegate's favorite, the second choice on that ballot was counted in the next round — and so on.

The instant runoffs ended when one candidate cleared the 60 percent support threshold, or else the top two finishers were identified.

Valuing the full range of voter preferences is important, especially when there are more than two candidates in the race. Typically during a Utah convention, delegates sit through rounds of voting and counting ballots, which can take hours.

With delegates scattered across the state, using their phones or laptops for ranked-choice voting, the process was simplified and shortened considerably this spring. Candidates' speeches were uploaded to online platforms for delegates to watch, and mobile voting platforms such as Voatz and ElectionBuddy were made available for voting virtually.

Eight GOP contests required multiple rounds of counting, but all preferences were expressed on a single ballot. The most competitive race featured a dozen candidates vying for the nomination in the 1st congressional district. (GOP incumbent Rob Bishop is retiring after 18 years.) No candidate commanded 60 percent support, but 11 rounds of counting produced the two who will now square off in a June 30 primary.

Though most races at the virtual Democratic convention determined a winner after the first round of counting, the contest for the 1st District also yielded a pair of solid finishers now headed to the primary.

This wasn't the first time either party had used so-called RCV, but the all-virtual convention was new. Despite the process change, turnout skyrocketed and set new records for both parties: 93 percent of Republican delegates and 85 percent of Democratic delegates participated.

In a poll of 1,100 delegates by the state GOP, nearly 90 percent said they were very satisfied or satisfied with the online format while 72 percent said they liked the instant runoff better than multiple rounds of repeated voting. More than half said they'd prefer an online convention in the future, or a new hybrid combination of an in-person and online system.

Utah uses ranked-choice voting in other elections, too. A state law, enacted with bipartisan support two years ago, allows municipalities to pilot RCV systems through 2026. Election officials in two cities that experimented last fall said the system saved taxpayers money, contributed to a more positive campaign atmosphere and was received favorably by the electorate.

RCV is gaining significant traction in other local and state elections, and was used in presidential primaries for the first time this year. Combined with voting by mail or early and in-person, Democratic primary turnout doubled in Alaska, Nevada and Wyoming — and just about tripled in Kansas.

The alternative election format helped Republicans and Democrats alike to innovate this primary season — while keeping candidates and voters safe. In addition to being nonpartisan, it has the added benefit of being a commonsense and effective solution in the middle of a global pandemic.

Balancing health and democracy for the rest of this election year will require continued creativity from party and election officials. Utah proved that RCV is worth being central to the solution.