Richie is president and Daley a senior fellow at FairVote, a nonpartisan electoral reform group that promotes ranked-choice voting. This month Daley published "Unrigged: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy" (Liveright).

So much has changed in American life, and so quickly, that it's hard to believe it's been just four weeks since former Vice President Joe Biden shocked Sen. Bernie Sanders with a rout on Super Tuesday.

A race that had been unsettled for months, seemingly bound for a brokered convention, shifted decisively in Biden's direction over the course of just 72 hours. Several competitors exited the race and offered their endorsements, strong performances across the South gave him a large delegate lead and then Michael Bloomberg and Elizabeth Warren gave up as well.

Imagine for a moment that it hadn't worked out that way. Imagine Tom Steyer got closer to Biden in South Carolina, and Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar pressed on. Suppose Bloomberg's early momentum continued and it was only Warren who dropped out, prompting progressives to consolidate behind Sanders against a still-fractured field.

The consequences would have been far-reaching. The decisions to delay primaries across the Northeast, Midwest and South would have become so much more important — and the debate over postponing them very different. Imagine the intraparty fireworks after Sanders backers accused the Democratic establishment of postponing the contest to slow his path. Then imagine a brokered convention in July, at a time of continued social isolation because of the pandemic.

This is to say: It's a fluke the Democratic nomination appears as settled as it does now. Our electoral system may have dodged incomprehensible chaos — and only by days.

In the past weeks we've launched an urgent conversation about voting during the coronavirus outbreak. The nation may not return to normal before summer, perhaps not even then. Many are suggesting we expand vote-by-mail, make it easier to register online and plan for how we allow everyone a vote in November in a full and free election.

We need to get this crucial debate right. That means we need a solution that would have also worked if the coronavirus spread began earlier, or struck while the Democratic contests was still splintered among several candidates, none approaching the 1,991 delegates needed to secure the nomination.

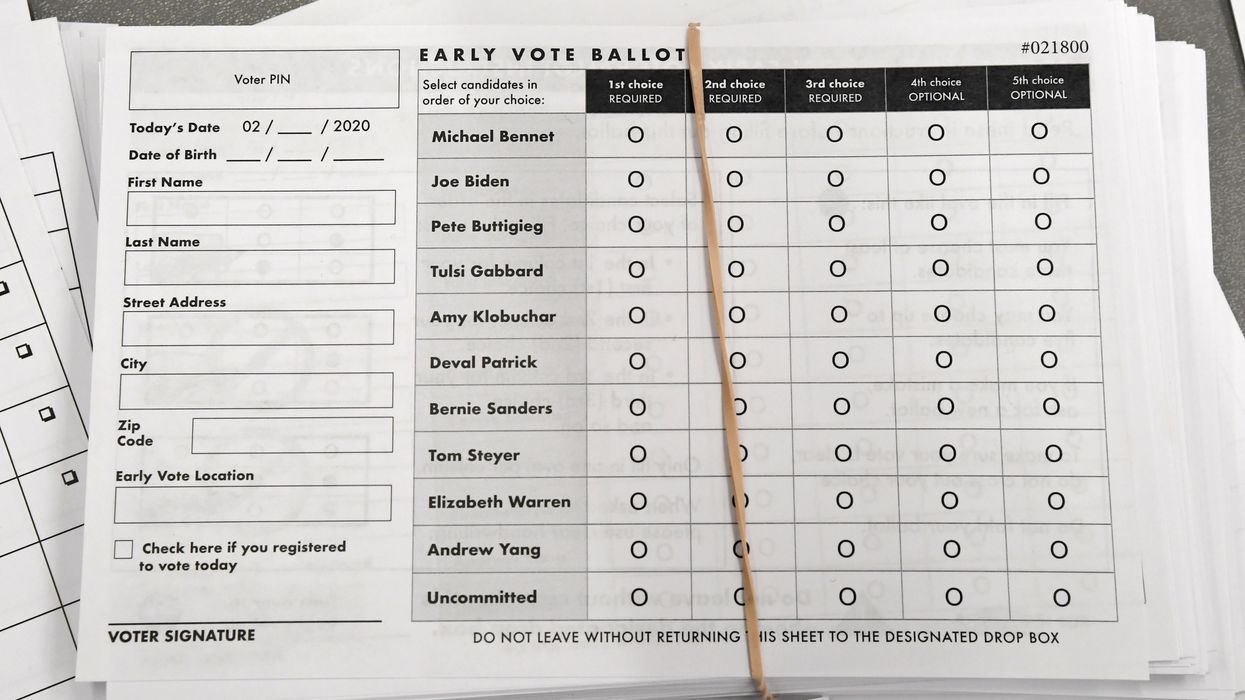

The solution is actually in front of us: Expand early voting by mail as well as ranked-choice voting. Five Democratic contests this year — in Nevada last month and Wyoming, Alaska, Hawaii and Kansas later this spring — allowed voters who cast ballots early to rank their favorite candidates in order of preference.

These states had previously used time-consuming, in-person caucuses that short-changed turnout. By expanding early voting and RCV, the state parties created the best of both worlds. Voters didn't have to spend hours on one night to make their voices heard, a challenge for many with evening jobs or child care responsibilities.

And by allowing these early voters to indicate all their acceptable choices, the rules made their voices as powerful as those who attended a caucus and could realign if their first choice fell short of earning delegates. This was a big hit in Nevada, where more than two-thirds of voters voted early and the system was easy to understand.

We don't need to imagine the benefits — especially now that, as of this writing, no fewer than 10 states with a combined 820 pledged delegates have delayed primaries, until June in all but a couple of places: Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Marland, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.

In Wyoming, where early voting with RCV has been underway, officials have seamlessly shifted the entire caucus to the mail — by promising collection centers for those who prefer to drop off their envelopes. Results will be delayed to allow people more time to request and return ballots, but nothing else needs to be rescheduled. Every vote that has already been cast will count. The same is true in Alaska, Hawaii and Kansas. While other states scramble under unpredictable circumstances, those election officials had already selected a plan that works during the Covid-19 outbreak.

But voting early or by mail is not enough. Just this month, well over 2 million voted early for a presidential candidate who got out of the race before that vote was counted. With RCV, those votes would move to the voters' next choices and they wouldn't be punished for a decision beyond their control. RCV would have given them a backup — and a voice.

Just as importantly, this emergency struck at a time when both parties' nominations appeared largely settled. The next could arrive in the middle of primary season or during a hotly divisive general election campaign.

If there were still half a dozen active Democratic candidates with nearly two dozen contests remaining, RCV plus early voting would allow the contests to continue and every voice to get fully heard.

Remember "electability," the issue over which Democrats obsessed endlessly? RCV would have enabled all voters to truly decide the issue. Biden may well be the final decision for the Democrats. But it was inarguably rushed, powered by a combination of fear that Sanders might be too risky and recognition a single-choice system would split the vote among all his rivals if they didn't drop out. A well-functioning system shouldn't come down to the luck of timing.

The coronavirus assures a lot is going to change — in American life and in our elections. The reforms we make now need to be thoughtful. And they need to be up to the task of improving elections that are likely to continue to be deeply polarized and feature big fields of candidates. Yes, we're going to need a fix for 2020. Let's make sure it improves the health of our elections for many more years to come.

Why does the Trump family always get a pass?