Richie is co-founder and senior advisor of FairVote.

When I gather with fellow electoral reformers it is clear I'm the "old guy"- not in age, but because I joined this fight in the 1980s. That gives me some credibility to share three lessons for winning change from efforts advancing ranked-choice voting, the “instant runoff” system designed to uphold majority rule in one election.

Lesson one is to have a clear vision of where to go, but with realism about how to get there and a refusal to lose.

My north star goal isn’t RCV alone. It’s the Fair Representation Act in Congress. Its combination of RCV with multimember districts results in a fairer distribution of power, which speaks to me deeply as a Quaker. All Quakers have the same power to speak. Every decision is made by consensus. It can be tedious, but also profound. We are expected to use our voice and listen to others.

Most Americans haven’t felt listened to for a long time. That's why in 1992 I helped found FairVote and became its first director, with a skimpy budget and decades of long days ahead of me.

I learned to keep my eye on both big goals and pragmatic ways to advance them. That balance led FairVote to identify approaches that catalyzed modern reform campaigns involving voter registration, the Electoral College and gerrymandering.

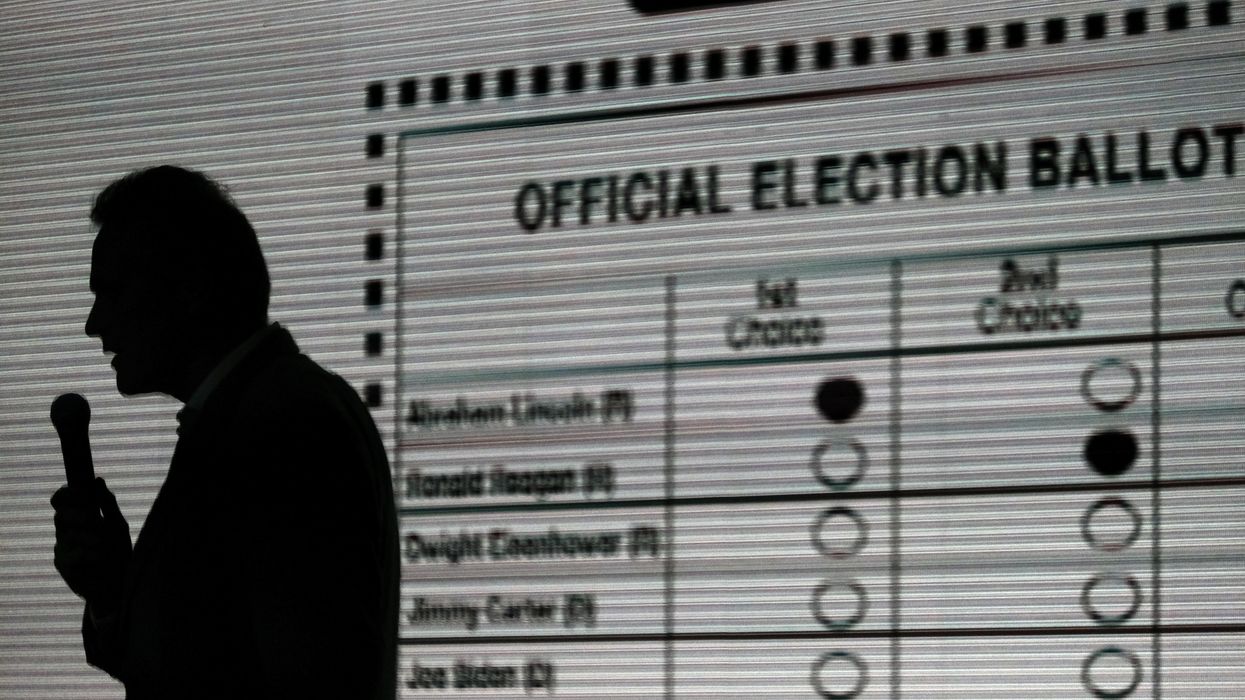

It also led me to RCV as combining impact and viability. The Quaker in me loves RCV because candidates have reasons to listen to more voters and voters to more candidates. Crucially, RCV also solves a problem we can immediately understand: It avoids “spoilers” when more than two candidates run. RCV made sense in 1992 when Ross Perot cut into George W. Bush’s base and in 2000 when Ralph Nader spoiled the election for Al Gore.

But making sense wasn’t enough. At first, voting machines couldn’t handle RCV, and incumbents were nervous about unintended consequences. To show a proof of concept we convinced a string of cities to replace their expensive runoff elections with instant runoffs.

A few repeals due to back luck slowed us down, but we didn’t give up. We kept showing how well RCV worked and blocked further repeals. We kept looking for state opportunities.

In 2010, Maine’s biggest city passed RCV, while a polarizing candidate was elected governor with only 37 percent. A new state campaign for RCV blossomed, and Mainers passed it in 2016.

With this new momentum, New York in 2019 started a streak of 27 straight city ballot measure wins for RCV. In 2020, four presidential primaries used RCV, and Alaskans backed their transformative RCV model. In 2021, Virginia Republicans nominated Gov. Glenn Youngkin with RCV, and the House passed pro-RCV legislation. RCV was an answer on “Jeopardy,” a New York Times crossword clue, and the means to pick the Oscar for Best Picture.

This progress depended on new allies. That’s the second lesson: Build your coalition with win-win solutions.

Take Alaska’s top-four RCV system that likely will be on the ballot this year in several states. It shows what's possible when seeking a bigger coalition.

When California adopted its top-two primary, third parties hated it. I’d always worked to open general elections, leading to spirited conversations with top-two advocates. We developed top-four RCV to work with them, not against them. Top-four opens both primary and general elections by doubling the number of advancing candidates, then using RCV to uphold majority rule. With the leadership and advocacy prowess of new allies, the rest is history.

That brings us to our third lesson: Seize the day.

This year we have a generational opportunity for change: A clear problem with a proven solution. A coalition guided by a common vision of elections giving us better choices, fairer representation and incentives to unite us. Working together, we can make this vision real for every American.