When it comes to fighting gerrymandering, the election produced one big step forward and one solid step back.

Voters in increasingly blue Virginia overwhelmingly approved a ballot measure to redesign the legislative map-making process starting next year in a bid to make it less dominated by partisan power plays. But at the same time Tuesday, the electorate in reliably red Missouri narrowly decided to go the other way, with a rare repudiation of a citizen-driven effort to fix democracy's challenges endorsed just two years ago.

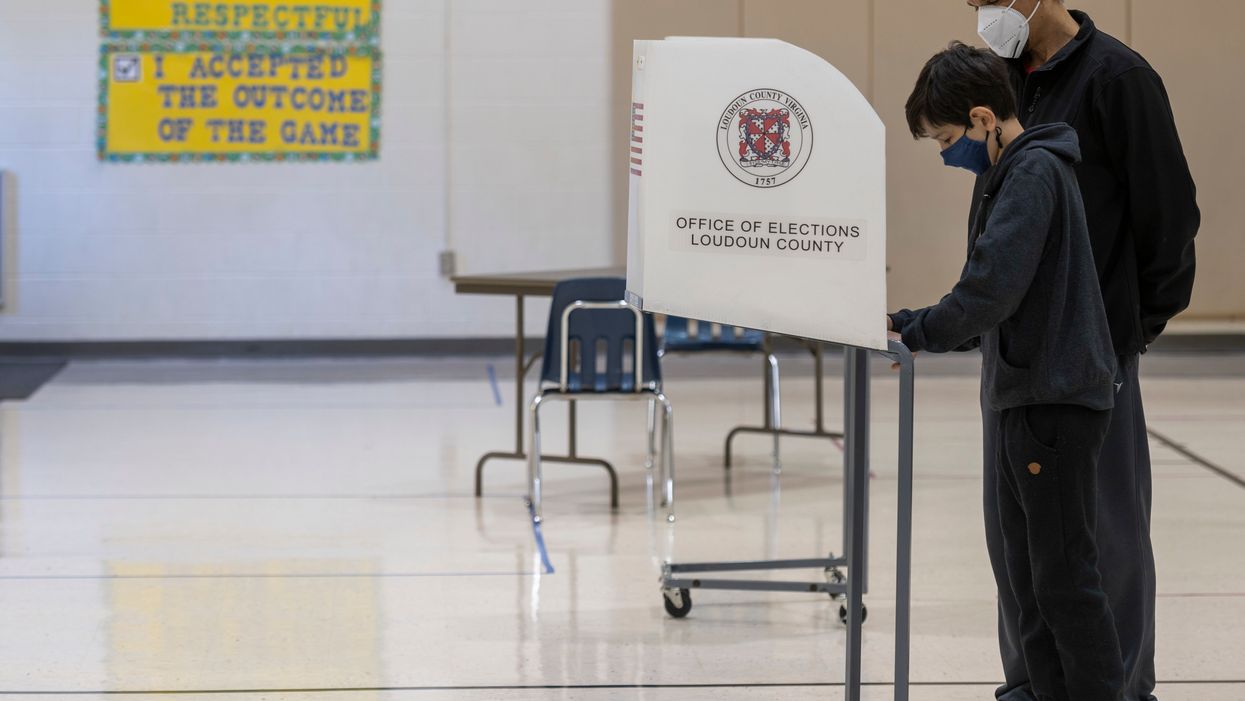

The votes were the last public input ahead of the national redrawing of congressional and state legislative district lines that happens once a decade, after the census. Results Tuesday suggest strongly that Republicans will control the mapmaking in a majority of states, as they did for the decade now ending. Measures to combat partisan gerrymandering failed to get on the ballot in four other states — Oregon, Nevada, Arkansas and North Dakota — because of the harsh difficulties of gathering petition signatures during a pandemic.

Here's more on the two states where voters had a chance to vote on the redistricting process:

Virginia

The measure that was approved — with 66 percent support in virtually complete results — will take line-drawing power away from the General Assembly and governor. Instead, a bipartisan commission of eight lawmakers and eight citizens will be in charge. If a supermajority of members don't approve of the new congressional and state legislative maps, then the state Supreme Court will step in to draw the lines.

The overhaul to Virginia's redistricting process was a long and hard-fought battle. Only after being endorsed by the General Assembly two sessions in a row was it put on the ballot.

Many Democrats were critical of the proposal, despite supporting it when they were the legislative minority in 2018. If the measure hadn't passed, Democrats in total control in Richmond would have had the power to execute a partisan gerrymander next year.

Those opposed to the change said it won't do enough to tackle partisan mapmaking since lawmakers will still be able to serve on the redistricting commission. They also pointed out that commissioners don't have to take racial equity into consideration when drawing maps.

While proponents conceded that a truly independent commission would have been better, they said this bipartisan panel is a good step forward for Virginia. Such genuinely independent panels will do the job next year, sometimes for both Congress and statehouses, in 13 states.

Missouri

A multifaceted package of governmental rules changes was approved with just 51 percent support — a margin of just 59,000 votes out of 2.9 million cast. The central redistricting provision sounds obscure but is meaningful: It eliminates the nonpartisan job of state demographer, created by a 60 percent statewide vote just two years ago to take charge of drawing the legislative lines, and creates in its place a pair of redistricting commissions appointed by the governor.

The reversal was put on the ballot by the Republicans in charge in Jefferson City, and they will now have the power to draw lines that assure they hold power. Opponents of their proposal say it will allow one of the most severe partisan gerrymanders in the country — potentially allowing a party winning just 50 percent of the overall vote to net as many as 65 percent of the General Assembly seats. It also breaks from standard districting practice nationwide, by decreeing that the districts be newly drawn based on the populations of adult citizens, not all people.

The measure may have passed because it was attached to a provision designed to be a sweetener with broad public appeal — a ban on lobbyist gifts and lower campaign contribution limits.