Why does The Fulcrum feature regular columns on health care in America?

U.S. health care spending grew 9.7 percent in 2020, reaching $4.1 trillion — 19.7 percent of the gross domestic product. Over the long term this is clearly unsustainable. If The Fulcrum is going to fulfill our mission as a place for informed discussions on repairing our democracy, we need to foster conversations on this vital segment of the economy. Maximizing the quality and reducing the cost of American medicine not only will make people's lives better, but will also generate dollars needed to invest in education, eliminating poverty or other critical areas. This series on breaking the rules aims to achieve that goal and spotlights the essential role the government will need to play.

Pearl is a clinical professor of plastic surgery at the Stanford University School of Medicine and is on the faculty of the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He is a former CEO of The Permanente Medical Group.

In the aftermath of the latest school shooting – this one in a Texas elementary school, claiming the lives of 19 children and two teachers – President Biden asked the nation: “When in God’s name will we stand up to the gun lobby?”

There’s no telling when lawmakers will find the courage to stand up to the National Rifle Association and its supporters. Sensible gun-safety laws have long eluded Congress, paving the way for more than 3,600 mass shootings in the United States since 2014.

Shootings are now the leading cause of death among American children, making gun violence much more than a societal problem. It is a medical and ethical problem, as well – a chronic disease, growing in prevalence and severity, with no cure in sight.

If elected leaders won’t help, medical professionals – despite being overworked and increasingly burned out – can and must.

Things I learned while fishing bullets out of bodies

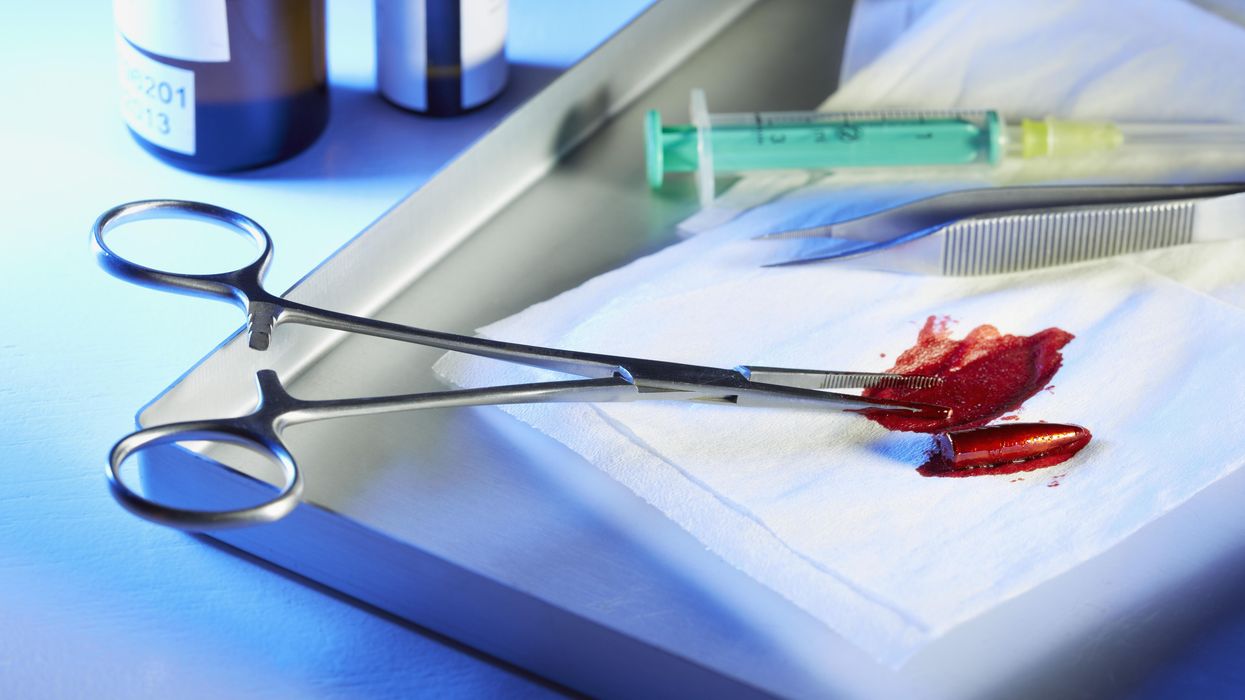

As a surgical resident, I spent long nights pulling bullet fragments out of legs, arms and chests.

I can tell you from experience that TV shows don’t portray gunshot wounds accurately. Bullets don’t pass through the body in a clean, linear path like an arrow. Once a bullet penetrates the skin, it spins and shatters, creating a wide path of destruction.

My responsibilities as a resident were to stop the bleeding, repair the organs, save a life.

For clinicians who treat gunshot victims, the technical aspects of care are fairly rote and routine, no different than removing dead intestines or bringing freshly oxygenated blood to a failing heart. The work isn’t easy, but the treatment plan is well-circumscribed: starting when the ambulance arrives and ending when the patient is discharged or dead.

Throughout my surgical career, I never considered talking to my patients about gun safety or making sure their firearms were stored in a locked cabinet, away from kids. I never even asked if they owned firearms or had ever thought about using one to harm another person. I doubt any of my attending physicians did, either.

Times have changed and so have the responsibilities of health care professionals.

The clinician’s lane is now a highway

In 2018, the American College of Physicians published a position paper in the “Annals of Internal Medicine” on gun violence, with suggested approaches for curbing deaths and injuries.

Among dozens of recommendations, the report included two major deviations from past positions. One solution urged doctors to discuss with patients the risks of having a gun in the home. Another encouraged physicians to advocate for gun-safety legislation.

In response to the report, which the gun lobby deemed a massive overreach, the NRA tweeted: “Someone should tell self-important anti-gun doctors to stay in their lane.”

That tweet was posted just hours before a man shot and killed 12 people at a country music bar in Thousand Oaks, Calif. Quickly, doctors replied on Twitter with personal accounts of traumatic gun-related injuries they treated, all under the hashtag #ThisIsOurLane.

One of the more emotionally charged responses came from a forensic pathologist named Judy Melinek who replied: “Do you have any idea how many bullets I pull out of corpses weekly? This isn’t just my lane. It’s my f**king highway.”

Doctors are trained to keep their feelings in check, not letting displays of emotion distort their objectivity or compromise a patient’s care. Perhaps that’s why the 2018 spat between doctors and the NRA felt so different – and so significant.

Hundreds of health care professionals reacted online with a kind of emotion and venom people had never seen before. The uproar on Twitter highlighted long-held tensions between gun-lobbying groups and researchers on the topic of gun violence as a public-health issue, signaling to many that the fight had only just begun.

A gun in the home

In 1996, under intense lobbying pressure from the NRA, Congress passed a law barring the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from studying the public-health effects of gun violence. That legislative restriction, which still exists, came three years after a landmark CDC study undercut the NRA, finding that “a gun in a home does not make everyone safer.”

Ever since, researchers and the NRA have been embroiled in legislative disputes. In March 2019, an approved spending bill liberalized the restriction, somewhat, letting the CDC do research on the “causes” of gun violence. However, it stipulated that “none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the CDC may be used to advocate or promote gun control.”

The ACP position paper and all the doctors who’ve followed its recommendations were boldly choosing to step over the NRA’s preferred lane marker. In doing so, they’ve made families and communities safer. Now, in light of the latest mass shootings, doctors can and must do more to help. Here are three recommendations:

- Prevention. Talk to patients about ways to prevent gun-violence as you would in any other preventive-care conversation. Above all, urge parents to make sure kids can’t access and play with firearms.

- Mental health. Although we must be careful to avoid the illusory truth effect (the stigma-inducing assumption that gun violence is a “mental health problem”), we must be diligent in screening for suicidal and violent ideations in the doctor’s office; offering judgement-free assistance and vital resources.

- Influence. Doctors and nurses remain the world’s most trusted professionals. Now is the time to use that trust to demand strict gun-safety laws. Tell your representatives in Congress that you support background checks, assault rifle bans, 3D-printing bans and 48-hour delays for gun permits. Insist that Congress act now before thousands more die needlessly.

Guns kill 40,000 Americans each year — resulting in 10 times more gun-related deaths than the next four richest countries combined. By promoting gun safety to patients and politicians, alike, health care professionals can do their part to prevent the next horrific mass shooting.

Note: Portions of this article were excerpted, with the author’s permission, from the book “ Uncaring: How the Culture of Medicine Kills Doctors & Patients.”

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift