James-Christian B. Blockwood, a former senior career senior executive in Federal Government, is Executive Vice President of the Partnership for Public Service and a Fellow of the National Academy of Public Administration.

It’s nearing spring before an election year, a time when the next round of presidential hopefuls usually line up and declare their intentions. Perhaps it’s also a time to pause and reflect on our nation’s leaders more broadly.

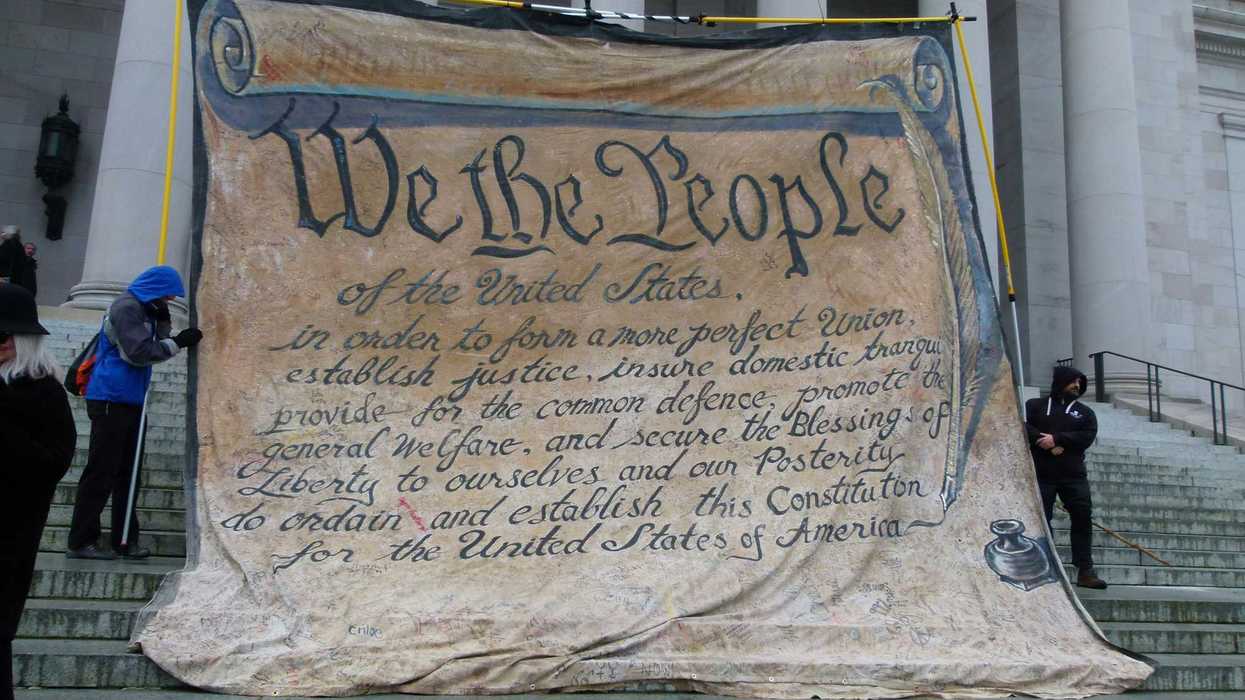

We have long relied on three branches of government—legislative, executive and judicial—to make, implement and interpret law. Our system’s highest leadership includes the president, 100 senators, 435 representatives and nine justices, all of whom serve more than 330 million Americans (and impact millions more). The foundation of our democracy relies on these three branches of government working well while also counterbalancing one another. Unfortunately, we have seen a recent struggle in choosing leaders across all three branches. Is this an exception or a trend? And, is either acceptable?

My answer: atypical leadership paths and contemptuous confirmations and elections are becoming more common. We need to improve the selection process for those serving at the highest levels of our government, introduce new leadership standards, amend laws, and reevaluate our overall political culture. While there are many reasons we choose to support certain leaders—policy positions, political philosophy and emotional appeal among the top—we should also consider management expertise, ethos and adherence to constitutional norms.

Electing a President

This recent struggle in electing leaders is a painful reminder that, just over two years ago, we had a transfer of presidential power that did not follow norms, would not be characterized as cooperative, cast doubt on the legitimacy of our electoral process and is associated with an insurrection many have called one of the greatest threats to democracy in modern times (the effects of which continue to haunt with little sign of relenting).

The president is generally considered our single most important leader. How this person comes into power—which is representative of us as a nation—should be a hard-fought contest at the polls followed by a smooth, seamless inauguration and presidential transition. The last presidential election and ensuing transfer of power was contentious and marred by partisanship.

Installing a Justice

There was also a less-than-ideal display of partisan politics in recent additions to the Supreme Court. Of the three last candidates—who must possess character and objectivity above reproach to effectively serve on the bench of our highest court—one was controversially accused of sexual misconduct, another faced an audacious line of questioning that would suggest an absurd unwillingness or inability to comprehend basic biology, and the other was enveloped in a debate over the appropriateness of a rushed confirmation (eight days before the next presidential election).

The confirmation process is necessary, and ultimately all three candidates became associate justices; however, their nominations arguably made our apolitical branch more partisan than ever and subject to outside influence. Even now, with a full bench, actions and appearances of justices are raising ethical concerns around partisanship. This surely makes our next appointments to the Court subject to greater scrutiny and suspicion—both through a political lens.

Choosing a Speaker

Not since 1855 has Congress needed multiple rounds of voting to select a Speaker of the House. Political infighting and division over rules have always been on full display and should be expected. But, in selecting our 55th Speaker, the divisiveness was excessive and arguably imprudent. A nominee typically needs 218 votes if every member participates. This Congress required 15 rounds (and a great deal of political jockeying and concessions) to get there. Congress by design is partisan, yet the fraction within parties further highlights a deepening divide and creates a near impossible situation to effectively lead.

Who should represent us?

Should we feel confident in a system of government that requires an extreme amount of administrative and legal action—which, frankly, most of us find hard to grasp—during leadership change? Should we be concerned that all three branches that govern the greatest nation on earth struggle to install new leadership? Should we celebrate that these may be some of our most transparent, participative times that demonstrate we do not select our most consequential leaders lightly?

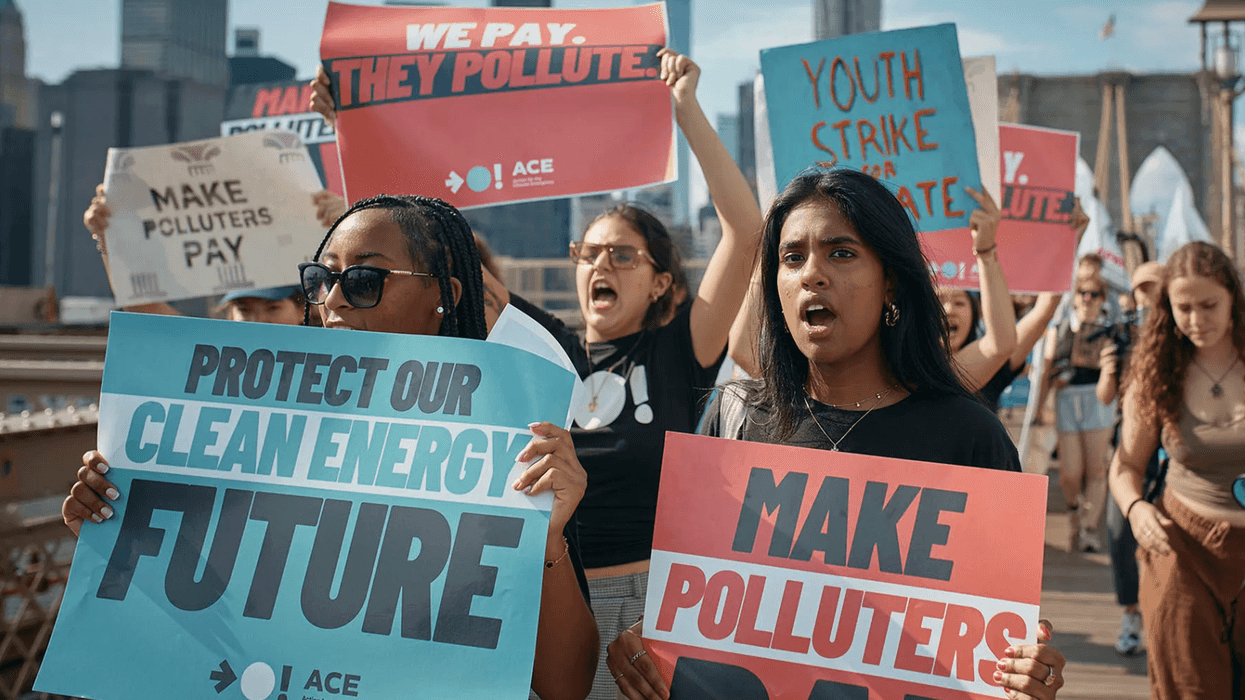

Recent events and leadership change at the highest levels of government show our democracy is fragile, and Americans should safeguard what makes us a great society—a democratic process that allows us to choose our leaders. We should elect, appoint and be represented by the best our country has to offer, and we should ensure our processes for doing so yield the best outcomes. We should balance discernment with passion when supporting a candidate or casting a vote. We should expect our elected leaders, though not perfect, to honorably serve the nation and faithfully fulfill their obligations to us.

How can we make transitions more seamless and choose better leaders?

Despite 74 percent of Americans indicating it’s important for government officials in Washington, D.C., to compromise, 58 percent have zero confidence that Congress will work in a bipartisan manner over the next two years. In such a partisan and fickle environment, we need strong leaders—principled in character, selfless in their motivations and willing to adopt a spirit of collaboration.

We must expect leaders to respect norms and question those who we feel will not lead to progress on longstanding challenges and enrich our lives. To this end, we can help ensure more effective leadership by 1) demanding presidential candidates honor electoral results and presidential transition processes, 2) regularizing the system for Supreme Court Justices and establishing term limits, and 3) requiring support for the Speaker of the House from a dedicated number of members representing both parties.

We also need models, laws and culture to help reinforce what we expect from our leaders. Government leaders at all levels, and especially at the highest levels, should embrace the Public Service Leadership Model that offers a standard for effective federal leadership, centered on stewardship of public trust and commitment to public good. Last year, a group of bipartisan lawmakers worked together to introduce the Presidential Transition Improvement Act, which aims to improve the information, resources and process for a declared winner of a presidential election. The 117th Congress Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress reimagined how to work together and created a bipartisan agenda to identify issues (and truly commit to fixing them).

There are many reasons why we rally behind a president or support the nomination of a Justice or Speaker, and we should take into account important factors that deal with good governance, stewardship and public trust. Selecting our nation’s leaders is becoming increasingly complex and challenging, but we can make it more effective by ensuring the processes—for elections as well as appointments—reinforce democracy rather than erode our confidence in it.