Making Election Day a new federal holiday has been one of the highest-profile parts of the Democrats' sweeping package for reforming elections, campaign finance and government ethics.

Plenty of prominent members of Congress such as Elijah Cummings of Maryland, who is in his 13th term and a committee chairman, praised the holiday provision when the House debated the bill this spring.

The Associated Press mentioned the holiday language in stories about passage of the legislation, known as HR 1. So did CNN, Fox News, The Washington Post and The New York Times. Leading good-government advocacy groups, including Public Citizen, shined a light on the possibility of a holiday in praising the measure's advancement.

And what do all of them have in common? They all got it wrong.

There is no such provision in HR 1 anymore.

The much-ballyhooed bid to give almost everyone the day off so they can go vote — which Majority Leader Mitch McConnell made a centerpiece of his vow to bury HR 1 in the Senate — died an almost silent death just before the measure moved through the House in March. There's no mention of a new holiday in the companion Senate legislation, either.

How that happened to such a prominent piece of government reform legislation, and the fact that so many prominent figures seemed not to realize it, illustrates how the process of trying to improve how government works can sometimes expose the government's own functional shortcomings.

Why it happened remains mostly a mystery.

A partisan punching bag

The story begins Jan. 3, the day Democrats took control of the House for the first time in six years and introduced their first bill, HR 1, which they dubbed the For the People Act.

Included in the 570 pages of legislative language were two paragraphs (Section 1903) creating an 11th federal government holiday. Defining the day — the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November of even-numbered years — took up one paragraph, while the second encouraged private companies to give their employees the day off as well.

Two weeks later, McConnell began what would be the first of a series of attacks on HR 1. In an op-ed in The Washington Post, he derisively labeled it the "Democrat Politician Protection Act." One of the provisions he singled out for ridicule was the proposed Election Day holiday.

With no GOP co-sponsors for HR 1 in the House — and almost no evidence of the Democrats soliciting Republican input in the bill's drafting — Democrats left themselves vulnerable to this sort of attack.

Because what McConnell didn't mention is that the Democrats have not been alone in proposing an Election Day holiday. In the 1970s and again in the 1990s, Republicans senators and House members signed on to legislation to do that very thing.

McConnell used Senate floor speeches to attack HR 1 on consecutive days in late January. The second time, he singled out the Election Day language as evidence the bill was "a political power grab that's smelling more and more like what it is."

It's in, then out, then in, then out

Fast forward to Feb. 26, when the only committee vote on HR 1 took place at the House Administration Committee, which has jurisdiction over most of federal election law. It was a genial but still partisan session, during which all 28 Republican amendments were rejected, a single Democratic amendment was adopted and the bill was approved — every single roll call falling along party lines.

But what went publicly unmentioned was that the lone adopted amendment did away with Section 1903 — the Election Day holiday language.

A week later, the bill was before the Rules Committee, which sets the ground rules for debating and trying to amend legislation on the House floor.

Inexplicably, the version of the bill taken up by the Rules panel had the Election Day holiday provision in it. But by the time the committee had finished its work, the language was on its way to oblivion again — this time never to return.

The chairwoman of House Administration, California Democrat Zoe Lofgren, testified before the Rules Committee that the proposal was being dropped as a concession to the committee's Republicans, who objected that their panel lacked jurisdiction over federal holidays.

Those same Republicans also complained that the multifaceted measure was being rushed through by the new majority and should have also been considered by several other committees with some jurisdiction over the policies affected.

"So, the manager's amendment strikes that federal election holiday as recommended by the minority," Lofgren testified the evening of March 5, in the cramped Rules Committee room on the top floor of the Capitol.

But the top Republican on her committee, Rodney Davis of Illinois, was having none of that. "We didn't participate in any crafting of this legislation — nor were we asked."

And the top Republican on Rules, Tom Cole of Oklahoma, pointed out that several senior Republicans had formally asked that their committees be allowed to consider HR 1 but were ignored.

"This highlights the rush process undertaken by the majority," he said.

The next day, the bill arrived on the House floor — the rank-and-file membership apparently oblivious to at least one aspect of the bill they were debating.

Cummings praised the inclusion of language that would "make it easier for hardworking Americans to find the time to vote by making Election Day a federal holiday."

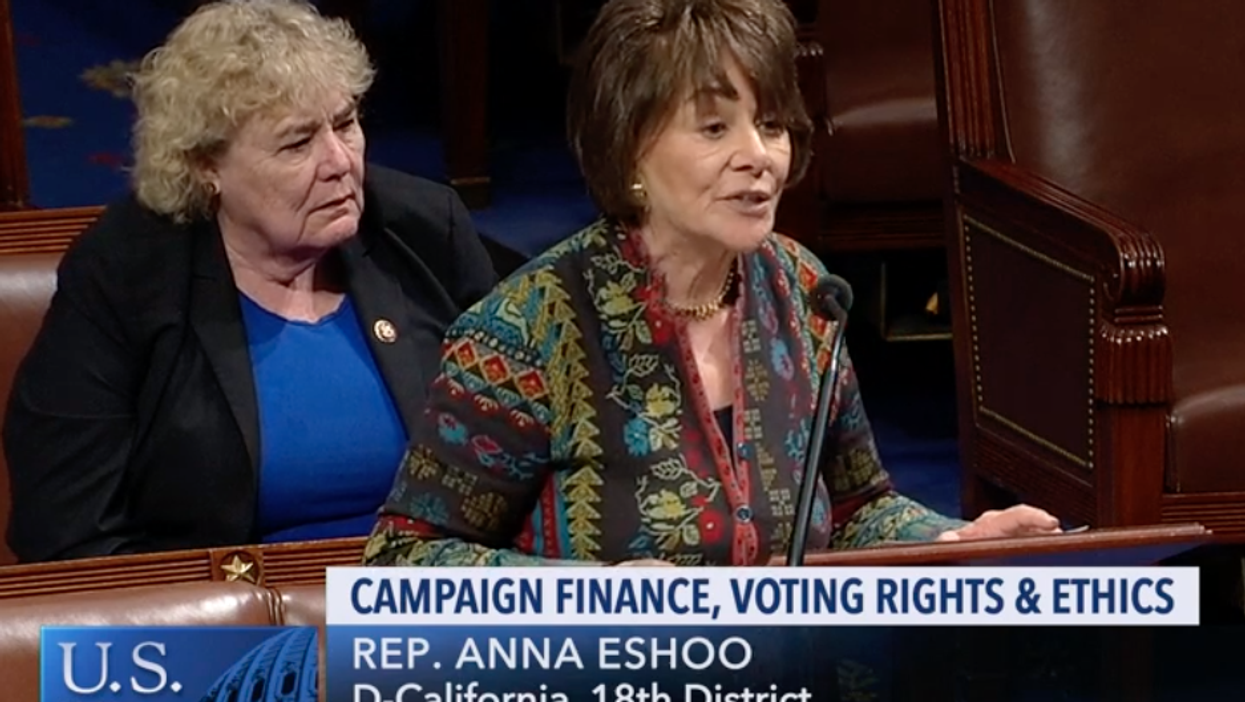

California Democrat Anna Eshoo, a 27-year House veteran and close ally of Speaker Nancy Pelosi, said she was "so proud" her stand-alone legislation, the Election Day Holiday Act, was part of HR 1. "People shouldn't have to choose between their job or their families," she said.

No clear answer on what really happened

So why did HR 1 get stripped of one of its most prominent provisions? And why did so few people notice?

The first and most straightforward reason for why the deletion was so widely missed: Members of Congress, their aides and, to be sure, journalists don't always have or take the time to read bills that run hundreds of pages long. This is especially so when legislation is moving quickly and outside of what's known on Capitol Hill as "regular order" — the sometimes slow, painstaking process of advancing a bill across all the parliamentary hurdles Congress has set for itself.

The reason why it happened remains muddled. While in her one public comment (at Rules) Lofgren gave a jurisdictional reason, one of her own aides (requesting anonymity so as not to overstep the boss) offered a more policy-focused rationale:

"HR 1 contains provisions requiring a minimum of two weeks of early voting as well as same-day voter registration and no-excuse absentee ballot voting. These provisions work together to form a comprehensive solution to the problem of people not being able to vote on a specific day. This expansion of the franchise negated the need for including a new federal holiday."

A spokeswoman for the Republicans on House Administration, Courtney Parella, asserted that the Democrats dropped the proposal because they faced criticism about the the cost of creating another holiday.

Others pointed to the pounding Democrats took from McConnell for the idea.

As for Eshoo, who claimed victory that her bill passed as part of HR 1, even though it didn't? Her office has not responded to requests for comment.

Meanwhile, the myth of the Election Day holiday provision lives on. In April, the freshman class of Democrats took to the House floor to boast of HR 1's passage as one of the top accomplishments of their first hundred days. "And the best part," crowed Sylvia Garcia of Houston, "Election Day would be a holiday."

And just last month, another first-termer from Houston, Lizzie Fletcher, told constituents during a telephone town hall meeting that HR 1 does a "a whole lot of things" — including making Election Day a federal holiday.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift