Swindell, an associate professor of public affairs at Arizona State University, studies how different levels of government interact and work together.

In a nation with more than 90,000 governments, responses to the coronavirus pandemic have highlighted the challenges posed by our system of federalism, where significant power rests with states and local governments.

Three weeks ago Wisconsin's Supreme Court overturned the governor's order for residents to stay at home — and then several cities and counties imposed their own restrictions, very similar to the governor's rules.

So who's running the show? It depends.

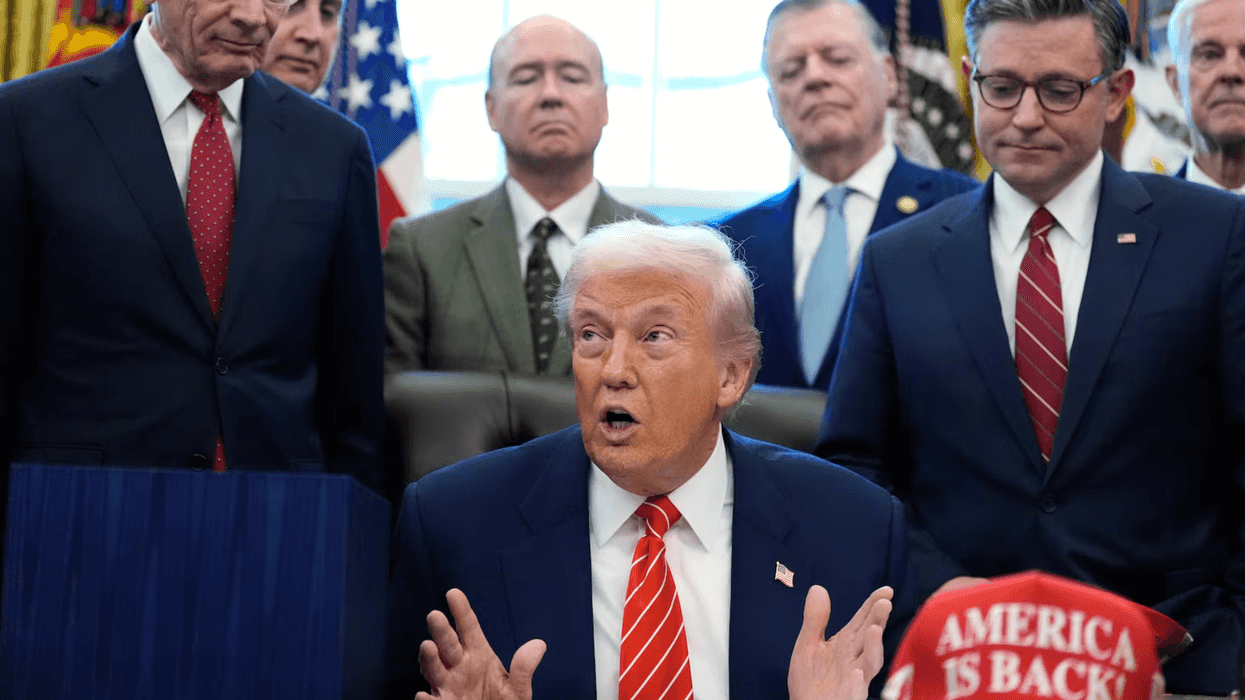

At the national level, President Trump has both told the 50 states to fend for themselves — and claimed to have the authority to force states to "reopen."

In the absence of nationwide coordination and leadership, governors have made their own decisions about how to contain the spread of the virus. Their decisions apply only to their own states, making the country a patchwork of varying efforts.

And with state governments lifting their lockdown restrictions to varying degrees, the patchwork is getting even more complicated. Factor in the powers and responsibilities of more than 3,000 counties, nearly 20,000 municipalities and almost 13,000 public school districts around the country, and it becomes clear that the answer to "Who's in charge?" is not so simple.

Who actually has the power to make binding decisions mostly depends on two factors. First, what's being decided: Is it about public health, police, hospitals, schools, barber shops or other businesses? Second: It depends on the state.

Historically, the United States has divided responsibilities for different services and functions across levels of government, so they could be tailored to regional preferences where possible.

For instance, jails are run locally or by counties while businesses get municipal and state licenses. Animal control laws, zoning and pothole repairs are typically handled by local governments. But states typically regulate businesses and industries, oversee welfare programs and manage major highways.

The national government handles things where widespread coordination and standards are important — like the national defense, Social Security, space exploration and commerce among the states.

Before the Great Depression, state and national government duties were more clearly differentiated. Since the 1930s the system has evolved, and the distinctions between which levels do what have blurred and blended.

For instance, states are in charge of public schools and universities, but the federal government makes school districts comply with rules about equal access for all students and provides money to support needy children and university research. Similarly, states build and maintain interstate highways but the federal government pays many of the costs.

Today, this mixing of responsibilities has made it difficult to form a nationally coordinated response to a pandemic in which the effects are mostly local. State and local officials have tried to respond but do not have federal-level resources or buying power.

The federal government may claim to be able to shut down the economy, but the truth is that states are responsible for regulating businesses operating within their boundaries. So the federal government can't order states to close down or reopen businesses.

On the other hand, the president or Congress can decide to give more money to states that go along with federal requests — and potentially cut funding to those that don't. States depend on federal money for criminal justice, education and highways funding, so this type of influence can be very effective.

Another aspect of American federalism worth noting: The Constitution ensures states retain powers beyond the federal government's but also remain very independent from each other. Each can develop its own policies and systems for delivering services.

That means potentially 50 approaches to combating a pandemic that does not respect state boundaries — and the state with the most lax standards in a sense setting the protection level for the whole nation. For instance, Arizona has reopened hair salons and theaters and now allows restaurants to serve inside. Neighboring California is remaining mostly closed, though its people may travel freely across the state line.

As if that weren't muddy enough, each state relates differently to its local governments. Constitutionally speaking, there are only two levels of government in the country — federal and state. Courts and legislatures have determined that local governments are extensions of states, with varying levels of independence.

In most states, local governments must seek permission from state legislatures before setting rules on topics ranging from drone flights to short-term rentals. But other states allow municipal governments to take on whatever responsibilities do not expressly belong to the state government.

All this means response to the pandemic varies not just from state to state, but also within states.

The way overlapping authority has played out is easy to see by looking at how one type of local government — school districts — responded to Covid-19. Sometimes, districts acted on their own. Other times, state departments of education ordered statewide closures, affecting districts that hadn't shut their doors. And some states never issued stay-at-home orders even though most districts had shut down.

As states begin to reopen, similarly confusing processes are happening in reverse. Some states with loosened restrictions have cities that want to maintain something close to sheltering in place — setting off disputes over state vs. local powers from Georgia and Utah to Texas and Colorado.

This diversity of precautions and actions can be seen as a strength of federalism, because it allows us to see how different responses affect the viral spread. Differing local and state decisions are creating experimental laboratories for finding different ways to move back into a fully operational economy.

And that's why your barbershop is still closed while the one in the next town or next state over is already open again.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Click here to read the original article.

![]()

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room