Bipartisan agreement is rare in these politically polarized days.

But that’s just what happened in response to ABC’s suspension of “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” The suspension followed the Federal Communications Commission chairman’s threat to punish the network for Kimmel’s comments about Charlie Kirk’s alleged killer.

It lit up the media. Democrats and civil libertarians denounced the FCC chairman Brendan Carr for violating the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of speech. Voices on the right, including Senator Ted Cruz, joined them.

Within a week, Kimmel’s show was back on the air.

While bipartisan agreement may be rare, it’s not surprising that it came in defense of the First Amendment – and a popular TV show. A recent poll found that a whopping 90% of respondents called the First Amendment “vital,” while 64% believed it’s so close to perfection that they wouldn’t change a word.

In just 45 words, it bars Congress from establishing or preventing the free exercise of religion, interfering with the peoples’ right to assemble and petition, or abridging freedom of speech or the press.

I’m a historian and scholar of modern U.S. law and politics. Here’s the story of why this amendment – now considered fundamental to American freedom and identity – wasn’t part of the original Constitution and how it was included later on.

Added three years after the Constitution was ratified, it resulted from political compromise and a change of heart by framer James Madison.

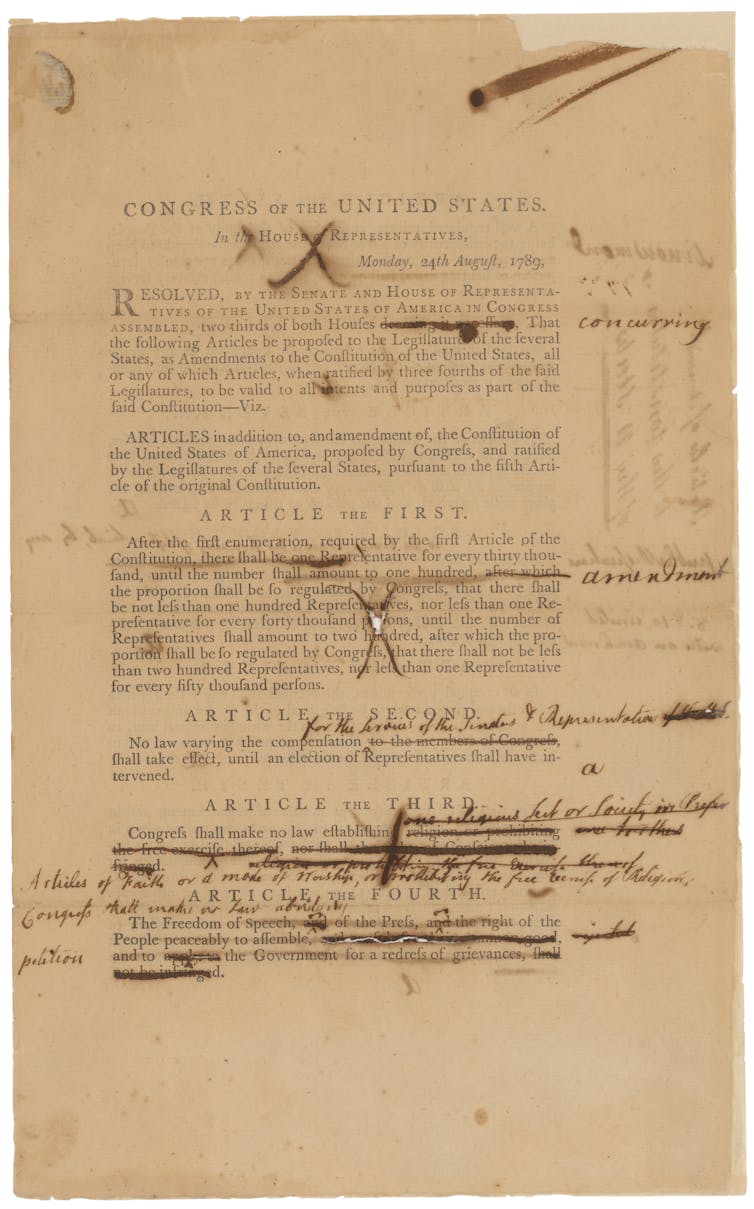

Handwritten revisions by senators during the process of altering and consolidating the amendments to the U.S. Constitution proposed by James Madison of Virginia. National Archives

Handwritten revisions by senators during the process of altering and consolidating the amendments to the U.S. Constitution proposed by James Madison of Virginia. National ArchivesSoured on bills of rights

Building a strong national government was the focus of Madison and the other delegates who met in Philadelphia in May 1787 to draft the Constitution.

They believed the government created by the Articles of Confederation after the colonists declared independence was dysfunctional, and the nation was disintegrating.

The government could not pay its debts, defend the frontier or protect commerce from interference by states and foreign governments.

Although Madison and the other framers aimed to create a stronger national government, they cared about protecting liberty. Many had helped create state constitutions that included pioneering bills of rights.

Madison himself played a critical role in securing passage in 1776 of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, a monument to civil liberties.

By the time the Constitutional Convention met, however, Madison had soured on such measures. During the 1780s, he had watched with alarm as state legislatures trampled on rights explicitly guaranteed by their constitutions. Bills of rights, he concluded, weren’t sufficient to protect rights.

So Madison and his colleagues put their faith in reinventing government.

No appetite to haggle

The Constitution they wrote created a government powerful enough to promote the national interests while maintaining a check on state legislatures. It also established a system of checks and balances that ensured federal power wasn’t abused.

In the convention’s waning days, delegates briefly discussed adding a bill of rights but unanimously decided against it. They had sweated through almost four months of a sweltering Philadelphia summer and were ready to go home. When Virginia’s John Rutledge noted “the extreme anxiety of many members of the Convention to bring the business to an end,” he was stating the obvious. With the Constitution in final form, few had the appetite to haggle over the provisions of a bill of rights.

That decision nearly proved fatal when the Constitution went to the states for ratification.

The new Constitution’s supporters, known as Federalists, faced fierce opposition from Anti-Federalists who charged that a powerful national government, unrestrained by a bill of rights, would inevitably lead to tyranny.

Ratification conventions in three of the most critical states – Massachusetts, New York and Virginia – were narrowly divided; ratification hung in the balance. Federalists resisted demands to make ratification contingent on amendments suggested by state conventions. But they agreed to add a bill of rights – after the Constitution was ratified and took effect.

That concession did the trick.

Harmless, possibly helpful

The three critical states ratified without condition, and by midsummer 1788, the Constitution had been approved.

However, when the First Congress met in March 1789, the Federalist majority didn’t prioritize a bill of rights. They had won and were ready to move on.

Madison, now a Federalist leader in the House of Representatives, insisted that his party keep its word. He warned that failure to do so would undermine trust in the new government and give Anti-Federalists ammunition to demand a new convention to do what Congress had left undone.

But Madison wasn’t just arguing for his party keeping its word. He had also changed his mind.

The ratification debates and Madison’s correspondence with Thomas Jefferson led him to think differently about a bill of rights. He now thought it harmless and possibly helpful. Its provisions, Madison conceded, might become “fundamental maxims of a free government” and part of “the national sentiment.” Broad popular support for a bill of rights might provide a check on government officials and how they wielded power.

Madison pushed his colleagues relentlessly. Wary of provisions that would weaken the national government, he developed a slate of amendments focused on individual rights. Ultimately, Congress approved 12 amendments – ensuring rights from freedom of speech to protection from cruel and unusual punishment – and sent them to the states for ratification.

First Amendment no cure-all

By the end of 1791, 10 of them – including the First Amendment ≠ had been ratified.

As Madison anticipated, the First Amendment wasn’t a cure for a government bent on suppressing dissent. From the Sedition Act in the 1790s to McCarthyism in the 1950s and the Trump administration’s assault on the First Amendment, government has used its awesome powers to pursue and punish critics.

On occasion, courts have intervened to protect First Amendment rights, a weapon Madison didn’t anticipate. But not always.

Perhaps the ultimate protection for First Amendment rights is “national sentiment,” as Madison suggested. Norm-breaking presidents can disregard the law, and judges may cave. But public sentiment is a powerful force, as Jimmy Kimmel can attest.

Donald Nieman is a Professor of History and Provost Emeritus, Binghamton University, State University of New York

Mayor Ravi Bhalla. Photo courtesy of the City of Hoboken

Mayor Ravi Bhalla. Photo courtesy of the City of Hoboken Washington Street rain garden. Photo courtesy of the City of Hoboken

Washington Street rain garden. Photo courtesy of the City of Hoboken