The massive outage that crippled Amazon Web Services this past October 20th sent shockwaves through the digital world. Overnight, the invisible backbone of our online lives buckled: Websites went dark, apps froze, transactions stalled, and billions of dollars in productivity and trust evaporated. For a few hours, the modern economy’s nervous system failed. And in that silence, something was revealed — how utterly dependent we have become on a single corporate infrastructure to keep our civilization’s pulse steady.

When Amazon sneezes, the world catches a fever. That is not a mark of efficiency or innovation. It is evidence of recklessness. For years, business leaders have mocked antitrust reformers like FTC Chair Lina Khan, dismissing warnings about the dangers of monopoly concentration as outdated paranoia. But the AWS outage was not a cyberattack or an act of God — it was simply the predictable outcome of a world that has traded resilience for convenience, diversity for cost-cutting, and independence for “efficiency.” Executives who proudly tout their “risk management frameworks” now find themselves helpless before a single vendor’s internal failure.

And the irony is brutal. Because those very same executives who love to rail against regulation and celebrate “the free market,” have built their empires on a single provider’s proprietary architecture — a fragile monoculture dressed up as digital progress. The lesson is as old as civilization: Centralization breeds vulnerability. When everything is connected through one hub, the entire system becomes hostage to its stability.

And yet, there is a strange silver lining. Outages like AWS’s, painful as they are, have the virtue of being visible. They hurt in real time. The pain is immediate, undeniable, and public. The fallout generates debate and, at least for a while, introspection. We may even take steps toward diversification — using multiple providers, investing in redundancy, designing systems that can withstand partial failure. The lesson, though learned the hard way, can be learned.

But what about the monopolies that never go down? The ones that never blink out for a few hours to expose their power?

Those may be even more dangerous, because they do not shock — they soothe and hum along. They shape the air we breathe, the stories we hear, the categories of thought we consider acceptable, and they do it quietly.

A case in point: The great consolidation of modern media: A handful of conglomerates controlling newspapers, television, digital platforms, film studios, and streaming — has created a quieter, subtler outage: An outage of dissent and and with it the slow but relentless erasure an informed and engaged citizenry-driven democracy.

When every channel is owned by the same few hands, when public debate is filtered through the same editorial logic, and when the same “respectable” voices decide what counts as “reasonable” and what is “extreme,” we drift into a cultural monoculture no less brittle than AWS’s server farms. But this one never goes offline. It keeps running—shaping minds, narrowing horizons, policing language, and quietly defining the limits of permissible thought.

You don’t have to look far for proof. For more than two years, while much of the world took to the streets in outrage, the American media averted its gaze from the genocide in Gaza – the one that has been financed in our name by our own tax dollars. When it finally did turn its attention to the story – when images of children dying of famine became too unbearable to ignore – it did so in the antiseptic language of “conflict” and “security,” filtering suffering through euphemism and imbalance. And all along, Pro-Israel voices dominated the airwaves, while those speaking for the other side were marginalized, stripped of context, lectured and manhandled in interviews, and denied the empathy so readily extended to their adversaries. None of this was by accident.

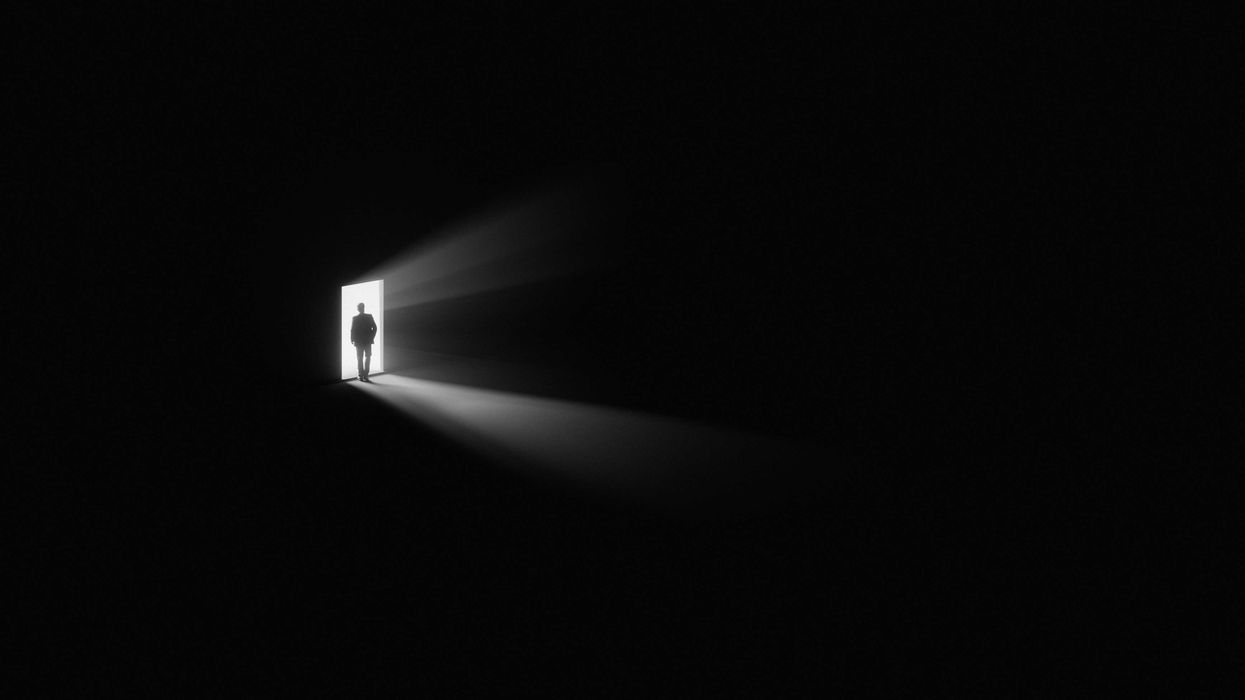

When democracy is being dismantled, there is no harsh moment of disruption to wake us up from that. No frozen app, no lost transaction. Only, perhaps, one day, the slow realization that our freedoms have eroded, that we are living inside a surveillance architecture of our own making, that the stories we tell ourselves about being informed and free were quietly rewritten while we scrolled. And by then, there may be no “reboot” — no simple fix, no alternative provider to migrate to.

That is the deeper danger of monopoly: Not the moment when it fails, but the long years when it works too well — when it serves power so efficiently that no one remembers what it was like to live outside its reach.

We will recover from AWS’s outage. We always do. But the question that should haunt us is not how to prevent the next system crash. It’s how to prevent the far greater one — the silent crash of democratic agency, cultural plurality, and free thought — that happens not when the lights go out, but when they shine only on what we are allowed to see.

Ahmed Bouzid is the co-founder of The True Representation Movement.