On the surface, the idea of conducting elections mainly by mail appears deceptively simple. It evokes images of a serious-minded citizen at the kitchen table, poring over information about candidates before thoughtfully marking a ballot, slipping it in an envelope and dropping it in the corner mailbox.

But the history of recent elections show that, even though such absentee ballots have accounted for only a quarter or so of the total vote, the system has faced serious obstacles. Suddenly doubling or even tripling the mail-in volume, which looks very plausible this November because of the coronavirus, will only magnify those challenges.

Compounding the problems is how the issue has become yet another partisan fight — with Democrats all in favor and President Trump pushing Republicans to oppose efforts to make voting by mail more available and reliable. The president's vastly overblown claims about a looming explosion of voter fraud, in particular, are overshadowing genuine worries about the abilities of election officials and the Postal Service to handle the coming surge of ballot envelopes.

Consider just two elections last month.

The Wisconsin Elections Commission reported last week that nearly two-thirds of the 1.6 million people who participated in the spring primary cast ballots by mail. That's nearly six times the number for any other primary in the state's history.

But the surge left election officials short of basic supplies, including 600,000 envelopes. The commission reported that in Milwaukee, the state's largest city, about 2,700 absentee ballots were inadvertently never sent out. And in another population center, Appleton and Oshkosh, computer and mailing problems combined to cause about 1,600 absentee ballots to never get processed.

Meanwhile, nearly 10 percent of the ballots could not be delivered for the first mostly mail-in election in Maryland history, to fill the Baltimore congressional seat opened with the death of the venerable Democrat Elijah Cummings. And the problem is getting worse ahead of the statewide primaries next week: More than 1 million forms will not be produced in time to make good on a mail-voting-for everyone promise in the state's biggest city and its biggest county, Montgomery, adjacent to Washington.

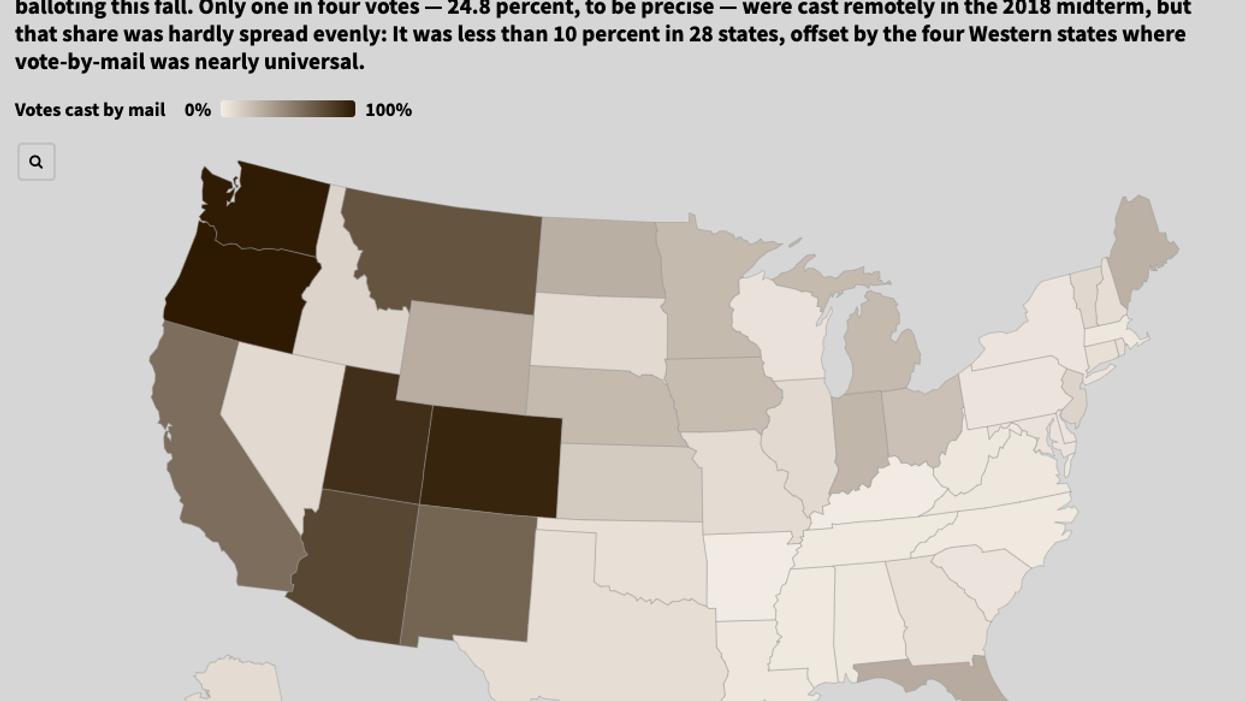

According to the most definitive survey of state election officials conducted after every general election — by the Election Assistance Commission, the main federal voting oversight office — 25 percent of all votes came through the mail in the 2018 congressional midterm, the same as in the presidential election two years before.

The EAC said that 42.4 million mail ballots were sent to voters ahead of the last election, but more than a quarter of them were never used — mainly because they were returned as undeliverable, got mangled in transit or were ignored by people who decided either to vote in person or not to vote at all.

That leaves 31 million votes submitted by mail. But the contents of 8 percent of them, or 2.5 million, never became part of the tabulated results. A small share of them had been completed by people who were not registered or eligible to vote, or by people who also voted in person.

But the EAC says three reasons accounted for the bulk of rejected ballots, and they were the same as the top reasons in every recent election:

- The ballot was not received on time at the election office. In 38 states, absentee ballots are counted only if they arrive on or before Election Day. The rest require an Election Day postmark but permit delivery between a day and 10 days later.

- The signature on the ballot was judged not to match the one on file with election officials. Signature matching has been a source of controversy and the subject of several lawsuits because in many cases there are few guidelines and no training given to the officials comparing the signatures.

- The ballot or return envelope was not signed at all by the voter -- or, in 11 states, was missing the signature of a required witness. Not all states have laws requiring voters to be informed of such mistakes and given a chance to fix them.

Whatever the reasons, the numbers do not support the assertion by the right-leaning Public Interest Legal Foundation last month — and widely repeated by allies of the president — that more than 28 million mailed in ballots "went missing" over the course of the past four national elections.

The National Vote at Home Institute, a leading advocacy group for making mail ballots the national norm, has been forceful in responding, pointing to data showing most of the ballots the conservative group is talking to were set aside by people who decided not to vote.

"It is important that this system is evaluated with facts, not misinformation," the group says.

Even with these hiccups, turnout in three of the states with universal vote-by-mail systems — Colorado, Oregon and Washington — was in the top eight among the 50 states last time. The exception was Utah, which was at the national average. Hawaii, which had the lowest turnout in 2018, is hoping to change that by mailing everyone ballots starting this this year.

And even without any more states relaxing their remote voting rules, or courts ordering them to do so, some experts were already predicting a record overall turnout eclipsing 70 percent in the fall presidential election.

Not every progressive group is enthusiastic about the move toward expanded voting by mail.

The NAACP and the Center for American Progress put out a joint report last month that praised efforts to make it easier for those who are quarantined or acting as caregivers to vote from home. But the report warned that "eliminating or reducing in-person options would inadvertently disenfranchise many African-American voters, voters with disabilities, American Indian and Alaskan Native voters."

The report notes that black people have a traditional preference for voting in person. But they also move more frequently than any other demographic group and are more likely to be homeless — both circumstances that make voting by mail more difficult. For disabled voters, many of the resources they need to vote independently are often only found at polling sites. Meanwhile, people living on tribal lands often do not have access to reliable postal service because there are not always official street addresses.

As a Brennan Center for Justice report released this month points out, conducting an election this fall mostly by mail requires overcoming numerous hurdles and making decisions that require action in the next few months. Among the obstacles it cites:

- Online absentee applications. While all but nine states permit online voter registration, only 15 allow people to request an absentee ballot online. Implementing such a system would take several weeks, at minimum, but the payoff is significant. Processing a paper absentee request form takes seven to ten times longer than processing an electronic request.

- Ballot printing. More absentee voters require larger orders to the printer. But in addition to printing the absentee ballots there is an assembly process required. All told, this may require advancing to the middle of next month the deadline for ordering absentee ballots for November.

- High-speed scanners. Tabulators at a precinct can scan about a dozen ballots a minute.

But to handle many thousands more absentee ballots than before, election officials are going to need scanners that can plow through as many as 300 ballots a minute — or else they won't be able to announce results on election night. Filling orders for these expensive machines can take months, and training needs to follow delivery, which is why the Brennan Center says the purchase orders need to be finished by this coming weekend.