Osterhout and McGinnis-Brown are research associates at Boise State University's Idaho Policy Institute.

As Americans and their elected representatives debate who should be allowed to vote and what rules should govern eligibility and registration, one key issue isn’t getting much attention: the ability for people to vote in languages other than English.

Communities with relatively high numbers of voting-age citizens with limited English-language proficiency tend to have lower voter turnout. This problem worsens when the people who are not proficient in English also don’t have very much education.

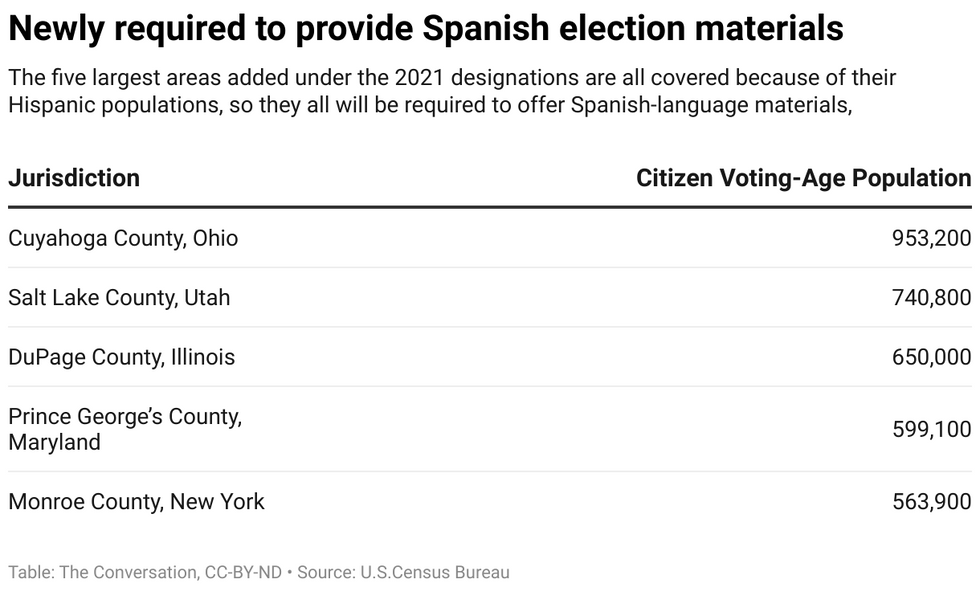

They include places like the counties containing Cleveland, Salt Lake City and Rochester, New York – and some counties directly neighboring Chicago and Washington, D.C.

The federal Voting Rights Act requires local officials in any community with significant groups of non-English-proficient citizens to provide election materials in that group’s language. That includes materials such as “any registration or voting notices, forms, instructions, assistance or other materials or information relating to the electoral process, including ballots.”

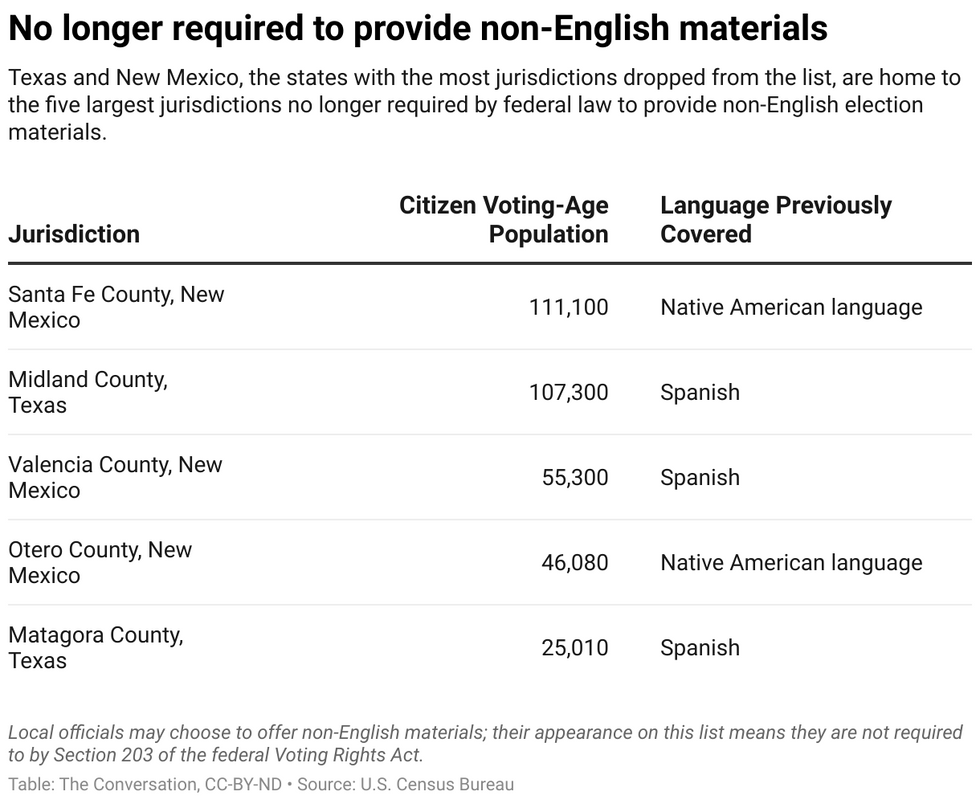

Every five years, the U.S. Census Bureau announces the list of voting jurisdictions – states, counties, municipalities, American Indian and Alaska Native areas – where those criteria are true. On Dec. 8, 2021, the latest list came out, declaring that 331 jurisdictions in 30 states must offer non-English voting materials. These locations are home to 80.2 million voting-age citizens, including 20 million people of Hispanic backgrounds.

We are researchers at Boise State University’s Idaho Policy Institute studying the effects of non-English election materials on voting behavior. We have eagerly awaited this release of newly covered areas, which we expect to affect the 2022 midterm election, the 2024 presidential election and beyond.

Who is covered?

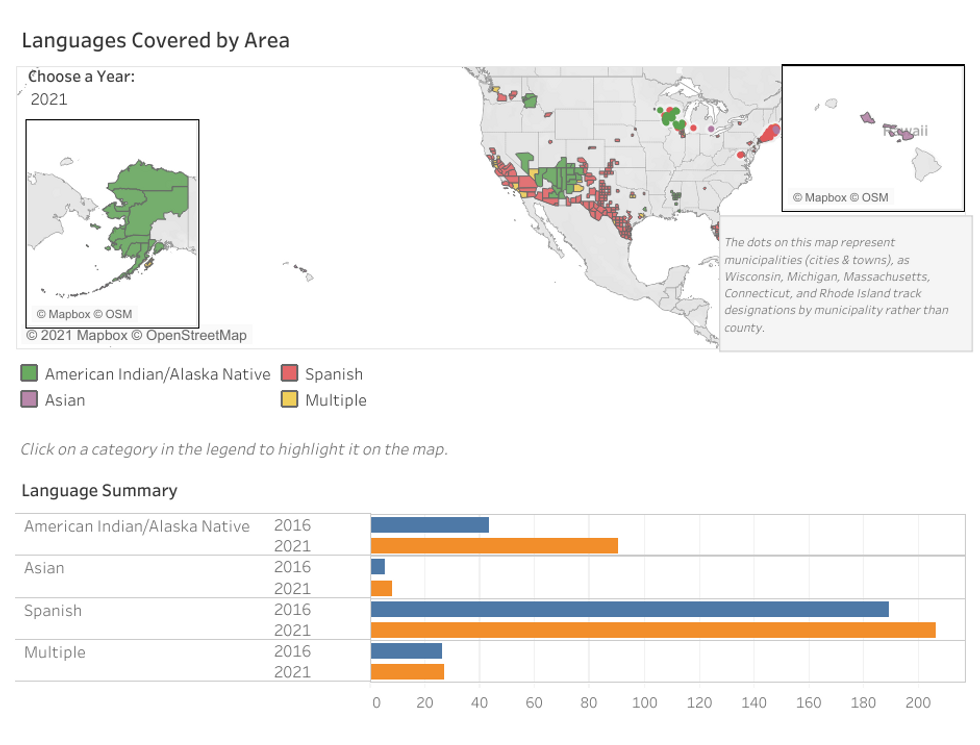

People who speak Spanish, Asian, Native American and Alaska Native languages are the focus of this policy, because the federal government has decided that they have “ suffered a history of exclusion from the political process.” Former University of Michigan Law professor Brenda Abdellal has said the Voting Rights Act provision should be expanded to include protections for other groups too, such as Arab Americans.

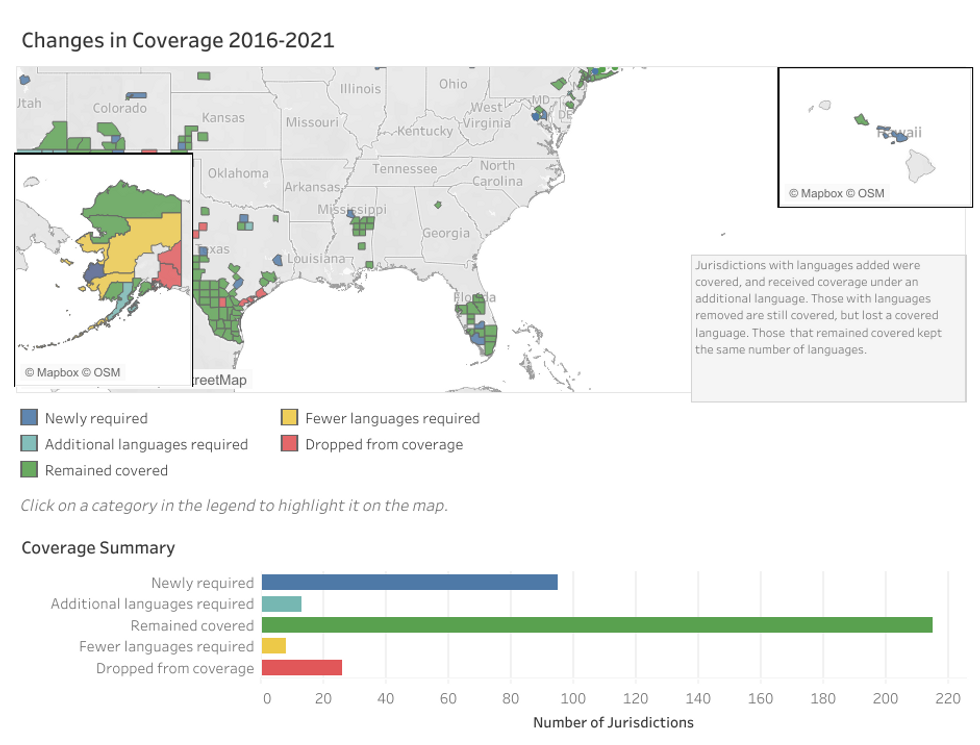

The 2021 Census Bureau designations create the largest increase to date in the number of jurisdictions that must provide non-English election materials and the number of people who will have access to them. Since the last designations in 2016, the number of covered jurisdictions has jumped by 68, a 26% increase. In comparison, the 2016 designations saw only a 6% increase in new jurisdictions over the prior 2011 designations.

California, Florida and Texas are still required to provide Spanish-language ballots for every statewide election, even if specific local communities don’t need to do so for their elections.

Although officials in jurisdictions not covered by the relevant Voting Rights Act provisions may also choose to offer these materials, we expect this new set of requirements to result in changes for a large portion of newly covered jurisdictions that have not, until now, offered those materials.

The number of voting-age citizens who can receive non-English materials is increasing as well. Under the 2016 designations, 68.6 million voting-age citizens lived in covered areas.

The 2021 designations add 11.6 million to that number. The combined language minority populations living in these areas saw a 22% increase in coverage under the 2021 designations, from 19.8 million to 24.2 million Americans.

Broken down by ethnicity, the number of Hispanic voting-age citizens living in jurisdictions required to offer Spanish-language ballots has increased by 22.7%. This increase is nearly double the 12.4% increase seen between 2011 and 2016.

Likewise, the number of Asian citizens living in jurisdictions required to offer Asian-language ballots has risen by 21.5%. That contrasts sharply with the 2% increase from 2011 to 2016. This change may reflect the ongoing growth of the Asian population in the U.S., which nearly doubled from 2000 to 2019 and is expected to double again by 2060.

The number of Alaska Native and American Indian citizens living in jurisdictions required to offer Alaska Native and American Indian language ballots has not increased as dramatically – by just 6.3%. However, the fact that it has increased at all is notable, as this is the first time since at least 2002 that the number has not decreased.

Wisconsin is the state with the most new jurisdictions, with 47, with many towns being newly covered for American Indian languages. While Wisconsin’s American Indian population has not grown as rapidly as its Black and Hispanic populations, other researchers have noted an ongoing demographic shift in Wisconsin over recent years, especially in smaller cities.

An important set of changes

Expanding the languages in which voting information is available boosts participation in the electoral process. The Voting Rights Act was amended in 1975 to require additional languages. In the following 30 years, Hispanic voter registration doubled.

In previous elections, counties that offered non-English assistance have seen increased voting by language minority groups, especially for first-generation citizens.

While there may be increased voting in those counties, other research suggests that election language assistance does not help increase voter registration for people who don’t speak English fluently.

Overall, studies show that language assistance, and especially Spanish-language ballots, make it easier for immigrant populations to engage in the election process, resulting in increased voter turnout among Hispanic citizens.

As minority populations continue to grow in many communities – the Hispanic population is the fastest-growing group in more than 2,000 counties – Section 203 of the Voting Rights Act will continue playing a key role in providing access to the voting booth for millions of Americans.

![]()