The Covid-19 pandemic has changed elections across the country, putting a new focus on the diverse, ever-changing and frequently opaque laws that govern how we go to the polls. It's a muddled landscape of rules about who can vote, where we vote and how we vote. Some of the most confusing laws are for individuals with felony convictions. In more than 30 states, they simply can't vote while still on parole. In others they can, but often only after fulfilling certain requirements. These rules are often unclear and not well-publicized, leading many, including many young people, to wonder whether they are eligible to vote.

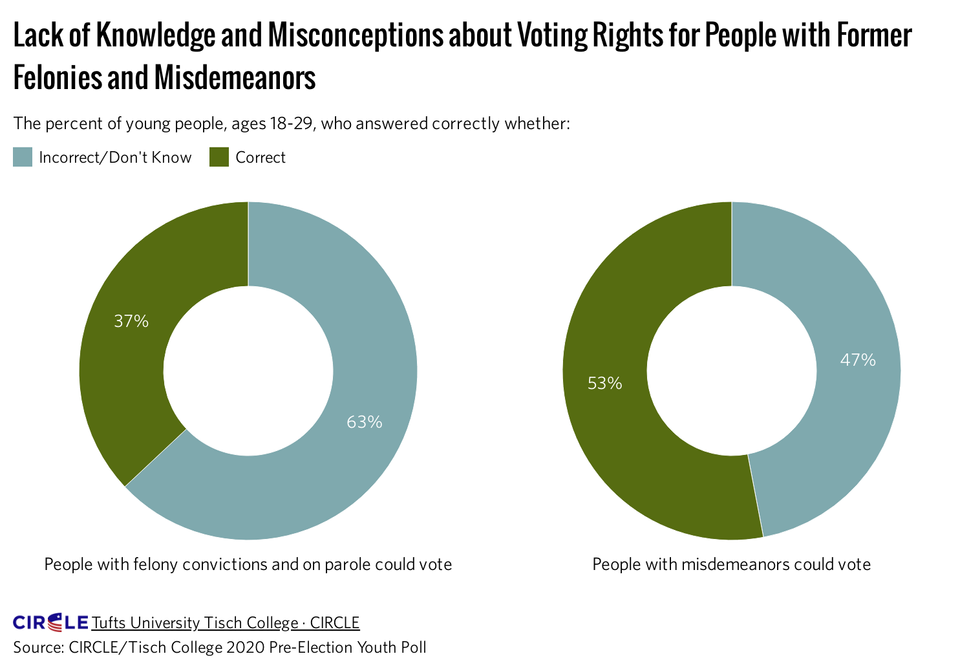

After having a considerable difficulty sorting through these laws ourselves this summer, the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement decided to learn what younger voters knew about felony voting laws. We found more than half of those aged 18-29 misunderstood convicted-felon laws. About one-third (37 percent) correctly identified whether people with past felony convictions could vote in their state and only 53 percent correctly said individuals who had committed misdemeanors could still vote — something which is true in all states.

These misconceptions disproportionately affect young Black, Latino and Native American communities. These populations are far more likely to be arrested, placed in juvenile detention facilities or incarcerated than those from other backgrounds, making questions about disenfranchisement and voting rights more pressing. Scholars estimate that one in three Americans will be arrested by the age of 23. And, like most dynamics connected to the criminal justice system in America, Black people are more affected by felony arrests. A 2019 study from The Sentencing Project found that one in 13 Black men in America is denied access to the ballot.

Ultimately, these findings underscore that misconceptions about election laws can make young people believe they cannot vote even when they are indeed eligible. Laws need to be clear and to be communicated properly. We must make sure we're providing all Americans — but especially young people who are new to elections — complete and accurate information about participating in democracy.

You can read our full analysis of young people and felony disenfranchisement laws here.

Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg is the director of the Center for Information and Research and Civic Learning and Engagement, part of the Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life at Tufts University. Alberto Medina is a communications specialist at Tisch College. Read more from The Fulcrum's Election Dissection.