The coronavirus pandemic continues to drive deliberations in states nationwide about how to conduct elections for the rest of this year and beyond.

In both reliably blue Nevada and relatively red Georgia, election officials on Tuesday decided to make their primaries wide open to voting by mail. Delaware became the latest state to delay its primary, while Wisconsin pressed ahead despite warnings about a shortage of poll workers.

The details of these developments:

Nevada

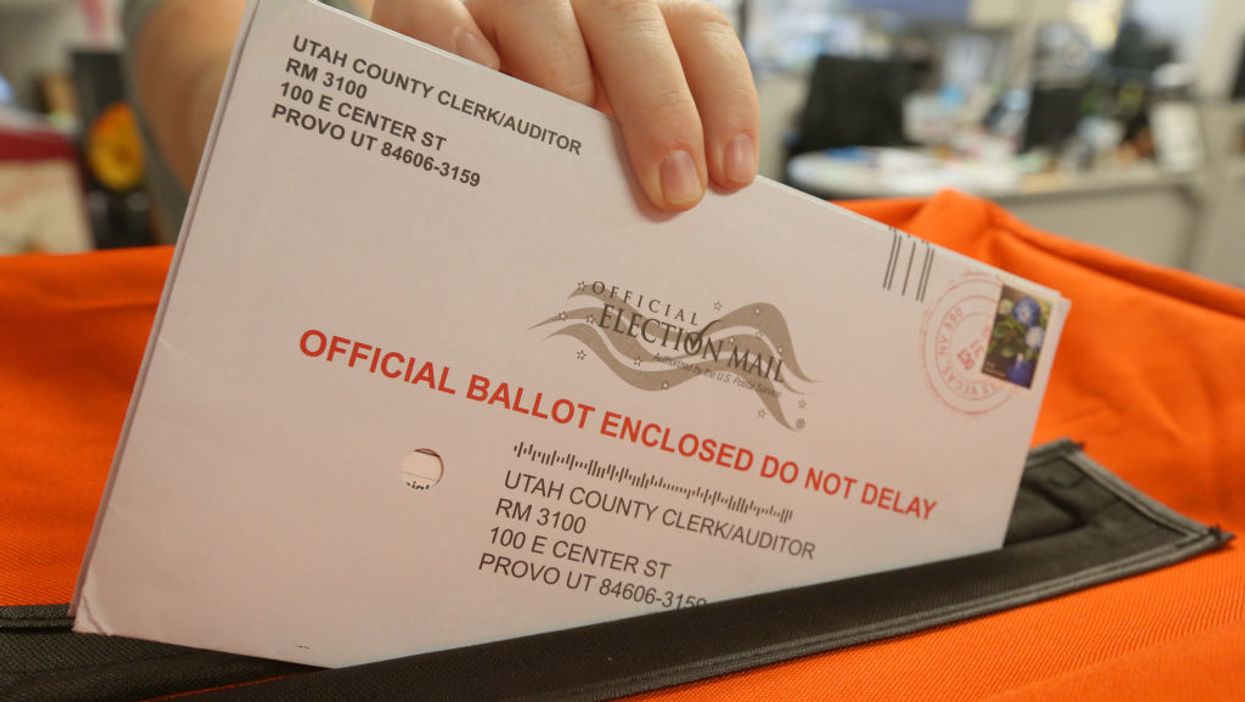

GOP Secretary of State Barbara Cegavske said all registered voters in the state will receive an absentee ballot well ahead of the June 9 primary. Voters may return it by mail or drop it off at a designated location. Postage will be free.

Cegavske noted that most of the state's poll workers are elderly and thus at a higher risk if they contract the coronavirus. Still, each of the 17 counties in Nevada will have one in-person polling location.

Georgia

All the state's voters will be sent an application to get a no-excuse-required absentee ballot in time to return it by May 19, the new date for the presidential primary but the originally scheduled date for congressional, state legislative, judicial and some local contests.

GOP Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger announced the move Tuesday, saying it was an attempt to encourage as many people as possible to vote from home and steer clear of polling places. But early voting and Election Day precincts will remain open.

Officials said the mailing will cost about $13 million.

While Georgia allows no-excuse absentee voting, only 7 percent of ballots were cast that way in the 2018 gubernatorial election.

Delaware

Democratic Gov. John Carney signed an executive order Tuesday postponing the presidential primary from April 28 to June 2. Primaries for other offices are scheduled for September.

That brings to five the number of states that have delayed their Democratic nomination contests to the second Tuesday after Memorial Day — making June 2 something of a miniature Super Tuesday, assuming there's still a contest between former Vice President Joe Biden and Sen. Bernie Sanders.

And the Pennsylvania's Legislature is expected to pass a bill in coming days proposing to likewise reschedule from April 28 to June 2. Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf is eager to sign the measure.

The other states to switch are Connecticut, Indiana, Maryland and Rhode Island. New Jersey, Montana, New Mexico, South Dakota and the District of Columbia are already set for that day.

Wisconsin

The next big-state primary remains on track for April 7, Democratic Gov. Tony Evers says, mainly because the ballot includes not only the presidential contest but also races for many local positions that would soon become vacant if the date is changed.

But on Tuesday the top election official in Madison, the second biggest city, said that about half the hired poll workers — 525 of them — have vowed not to show up that day, potentially leaving dozens of polling places unable to open. Clerks statewide are clamoring to hire replacements to make sure there are at least three officials in each place as the law requires. Some have proposed calling in the National Guard to man the voting sites.

Evers on Tuesday encouraged voters to request a ballot online and then vote absentee. Officials said requests were on pace to set a statewide record.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift