Wertheimer is the president of Democracy 21, which works to strengthen democracy by ensuring the integrity of our elections and more.

The House passed historic reform legislation to repair and strengthen the rules of our democracy on March 8.

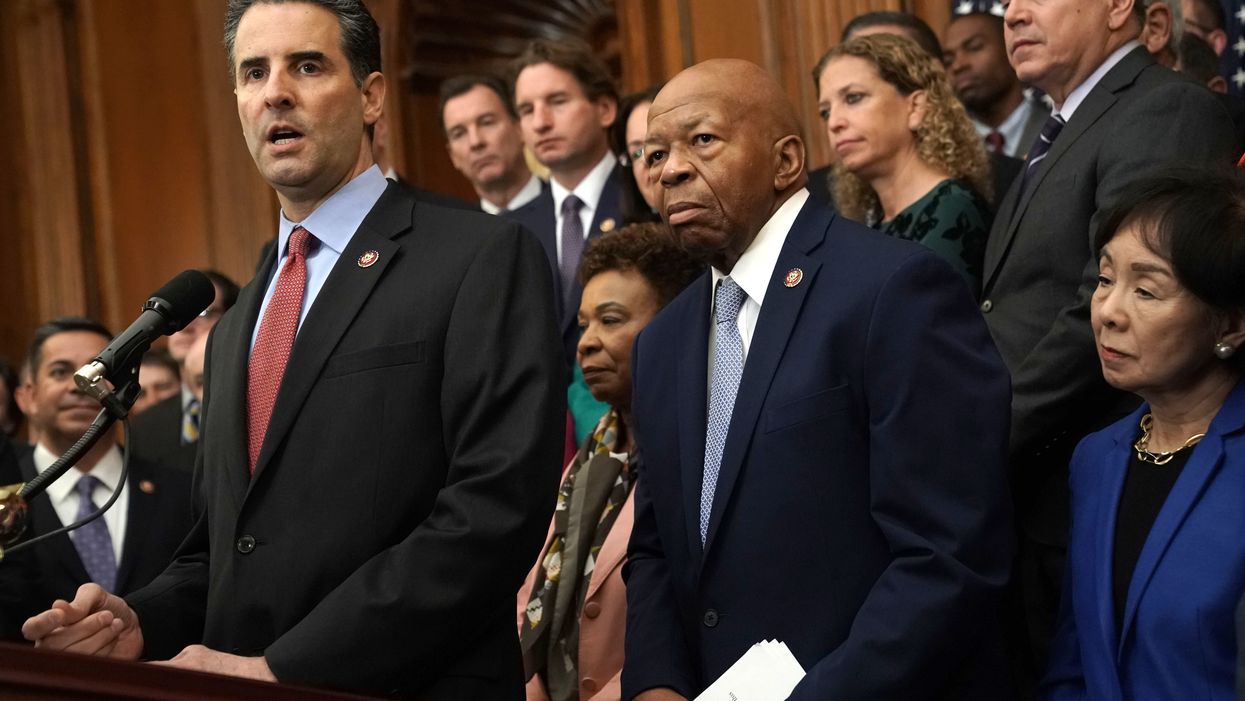

HR 1 is unprecedented, holistic reform legislation to fix our broken political system. It passed on a 234-193 party line vote, led by Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Rep. John Sarbanes. A companion bill was introduced in the Senate by Tom Udall with all 46 of his Democratic and independent colleagues as sponsors.

HR 1 provides essential reforms to address what's broken in our political system — money corruption, voter suppression and discrimination, extreme partisan gerrymandering, and government ethics abuses.

The key anti-corruption measure would create a small-donor, public matching funds system for presidential and congressional candidates, financed by a small surcharge on the fees and penalties assessed for corporate malfeasance and white-collar crimes. Without this alternative means to finance campaigns, officeholders will remain trapped in the vise-like grip of influence-seeking funders and Washington corruption will continue unabated.

Some have claimed HR 1 is simply a "message bill," but that is not the case. As Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne explained, it's "a marker, a bill worth fighting for in the future," and also "perhaps the most comprehensive political-reform proposal ever considered by our elected representatives."

In an NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll conducted in the fall of 2018, 77 percent said "reducing the influence of special interests and corruption in Washington" is "the most important, or a very important, issue facing the country."

Challenging Washington corruption became a major 2018 campaign theme for House Democrats, particularly challengers. The elections resulted in the largest vote margin in history for House Democrats and the most seats picked up since the 1974 post-Watergate election; 64 new House Democrats were elected.

These results sent a loud and clear message that the American people are fed up with the rigged system. The results were a key factor in passage of HR 1.

Deep citizen concern about Washington corruption can facilitate further breakthroughs in Congress, as it did with the enactment of major anti-corruption reforms following Watergate and the soft money scandals in the 1990s. In the battle ahead, President Trump is the poster child for the current corruption scandals in Washington.

It was no surprise to reform advocates when Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said he would not schedule a Senate vote in this Congress on HR 1. We never expected him to. McConnell will likely go down as the greatest obstructionist in Senate history. He has been obstructing anti-corruption bills for more than three decades, as well as blocking action on countless other bills. Reform advocates, however, have beaten McConnell before, in passing the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, also known as McCain-Feingold. We will do so again, if he remains in Congress.

Fundamental change takes time; such change rarely results from the political equivalent of a "big bang."

From the beginning, the effort to enact the democracy reforms in HR 1 has assumed a three-to-five-year strategy at least. With all congressional Democrats now on public record in support of HR 1 or its Senate counterpart, the battle moves to making breakthroughs with enough Senate Republicans to overcome a filibuster, and firming up waivering congressional Democrats.

For decades, efforts to achieve major campaign finance reforms had bipartisan leadership and support in Congress. I helped lead outside advocacy efforts to enact the two most significant bills of the modern era: The Federal Election Campaign Act Amendments of 1974 and the 2002 law. Both were bipartisan efforts.

The latter was enacted with the leadership of Republican John McCain, and the votes of a significant number of GOP senators, over the unyielding opposition of McConnell, who said that "the worst day of my political life was when President George W. Bush signed McCain-Feingold into law."

Times are different today.

The 2010 Citizens United decision by the Supreme Court was used by McConnell to organize almost universal opposition by congressional Republicans to enacting new campaign finance laws.

Today's partisan polarization in Congress has created special challenges for enacting the reforms necessary to revitalize democracy. Reform advocates, however, have a secret weapon: The American people overwhelmingly want an end to Washington corruption, and they want our rigged political system fixed. A grassroots uprising and the voice of citizens expressed through the ballot box will play a vital role in winning this battle.

Stage one of the strategy for victory has already been achieved. The blueprint for repairing our political system has been set by HR 1. The Declaration for American Democracy coalition of more than 135 national organizations, including my organization, Democracy 21, conducted extensive grassroots and Washington lobbying to pass the bill.

Stage two is playing out in the 2020 campaign. The coalition is taking various steps, including communicating directly with presidential campaigns and conducting grassroots activities, to advocate that all candidates make democracy reform a central part of their message. The candidates also are being asked to commit to making the democracy reforms in HR 1 a first priority if elected.

Groups in the coalition also will work to make breakthroughs with Senate Republicans to obtain the 60 votes needed to overcome a filibuster against HR 1. If not enough Republicans can be persuaded, alternative approaches will be explored to enact democracy reform without being subject to the filibuster rules.

Stage three will depend on the outcome of 2020. If a more responsive president and Senate are elected, and if House support for HR 1 remains intact, we will be on the doorstep of historic campaign finance, voting rights, redistricting and government ethics reforms in the next Congress.

Otherwise, the fight will continue in the next Congress, during the 2022 congressional elections and for as long as it takes to win this battle to protect our democracy and repair our political system.

We are not going away.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift