Maybe the moderators couldn't agree on how to pronounce the word "gerrymandering" in pregame warmups. How else to explain no questions about yesterday's Supreme Court ruling on partisan mapmaking?

Also, is election security not a thing anymore?

Moderators once again overlooked anything related to democracy reform during day two of the first round of Democratic presidential primary debates — as they did on day one. Nonetheless, some of the candidates found ways to slip in their views on topics such as voting rights, money in politics and the cycle of corruption in Washington.

The Fulcrum goes inside the numbers from last night's debate.

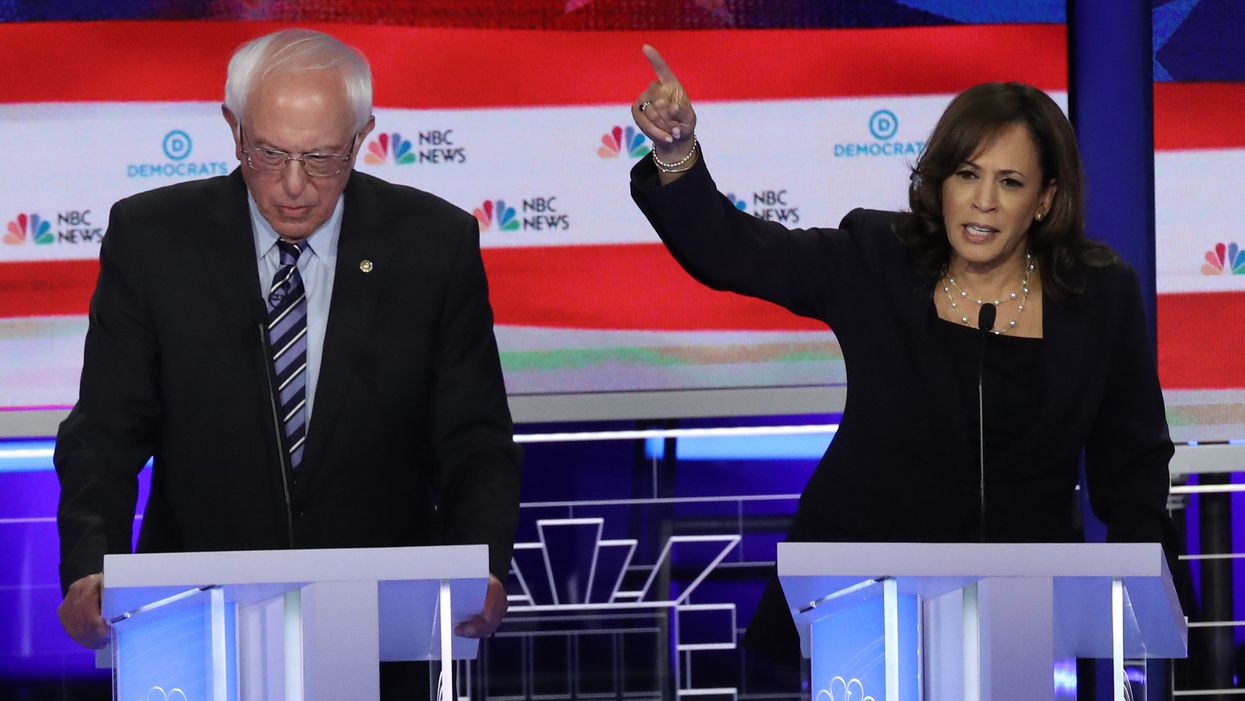

17 and 15: Minutes and seconds until the first mention of anything related to democracy reform. Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont led the way, rallying against big-money special interests.

"The issue is, who has the guts to take on Wall Street, to take on the fossil fuel industry, to take on the big-money interests who have unbelievable influence over the economic and political life of this country?"

5: "Reform" references. The word "reform" was used a handful of times during this debate, but not in reference to democracy reform. Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., former Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper, New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand and California Rep. Eric Swalwell instead spoke about immigration and gun reform.

6: Digs at money in politics. Sanders and Gillibrand dominated the conversation around money in politics during Thursday's debate. While Sanders mostly talked about eliminating special interests, Gillibrand went more in depth by referencing her plan to root out corruption through publicly funded elections.

1: Call for overturning Citizens United. Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet was the only candidate to call for invalidating the Supreme Court's 2010 ruling that allowed unlimited outside spending in elections.

3: Russian election interference mentions. California Sen. Kamala Harris, businessman Andrew Yang and Bennet all noted Russia's election interference as America's largest current threat.

3: Mentions of voting rights. Former Vice President Joe Biden and Harris both mentioned the Voting Rights Act, while Bennet spoke about the attack on voting rights in Shelby v. Holder.

1: Nod to gerrymandering. Bennet was alone on the debate stage in acknowledging the issue of gerrymandering in the wake of the Supreme Court's ruling on two cases of partisan mapmaking earlier in the day.

"We need to end gerrymandering in Washington. We need to end political gerrymandering in Washington. The court today said they couldn't do anything about it."

3: Candidates who said nothing of democracy reform. Author Marianne Williamson, Hickenlooper and Swalwell chose not to talk about any democracy reform issues during Thursday night's debate.

Reform quotes of the night

Gillibrand: "The truth is, until you go to the root of the corruption, the money in politics, the fact that Washington is run by the special interests, you are never going to solve any of these problems."

Buttigieg: "We've got to fix our democracy before it's too late. Get that right, climate, immigration, taxes, and every other issue gets better."