This is the first in a four-part series examining possible outcomes of state legislative elections in 2022 and their potential impact on policy-making.

As Congress has become mired in gridlock, passing few meaningful bills each year, state governments have become home to most consequential legislative activity. And with the Supreme Court leaving abortion law to the states and considering whether to allow legislatures more power over elections, that trend is only continuing.

That makes the 2022 midterm elections critical for anyone concerned not only about reproductive rights and elections but also education policy, infrastructure, health care and a host of other issues.

With seats up for grabs across the country, The Fulcrum is kicking off a series examining which state legislatures are in play and what possible outcomes mean for policy-making in 2023.

Historically, the presidential party almost always loses state legislative seats in the midterm elections, the only recent exception being the 2002 midterm elections in which Republicans gained in state legislatures under George W. Bush’s presidency, soon after the Sept. 11, 2001, attack that boosted his domestic popularity.

Still, several legislatures are close enough to fall on either side of the partisan line this November. The Fulcrum utilized ratings from Cnalysis and Sabato’s Crystal Ball to identify the most contentious legislative bodies, Ballotpedia data on midterm trends, and Campaign Legal Center redistricting data in order to examine likely outcomes in these states and what they mean for constituents and the country as a whole.

Both Cnalysis and Sabato use ratings systems that label races based on the likelihood of a particular outcome (tossup, solidly for Republicans, leaning towards Democrats, etc.). This series focuses mostly on states in the most competitive categories. This first installment examines the three states – Alaska, Connecticut and New Hampshire – where only one house of the bicameral legislature is within reach of the minority party this fall.

Alaska House of Representatives

With a total of 60 members, 40 in the House of Representatives and 20 in the Senate, Alaska has the smallest bicameral state legislature. Alaska currently has a divided government — while the Republican Party has firm control over the Senate and governor’s seat, the House is controlled by a bipartisan coalition, and has been since 2016.

Cnalysis gives the Alaska House of Representatives a rating of Lean R, predicting that 47 percent of districts will most likely go to Republicans, while 33 percent will most likely go to Democrats or Independents. In order for Democrats and their supporters to gain an outright majority, they would have to win four tossup districts, three Lean or Tilt D/I districts, as well as one Lean R district.

However, recent history shows that even with an outright Republican majority, the GOP can lose governing power: Republicans have lost control to bipartisan coalitions even when holding an admittedly slim majority on multiple occasions, as Independents and their own colleagues joined with Democrats. Still, Sabato’s Crystal Ball rates the House Lean R, citing retirements and the strengthening conservative wing as reasons why the coalition may fail, returning Alaska to a GOP trifecta.

Additionally, according to data from Ballotpedia, the Alaska House of Representatives does not appear to follow election trends in the way that many other states do. Democrats gained seats in the 2014 midterms despite the presidency being in their control, as well as in 2016 despite Donald Trump’s White House triumph. Meanwhile, in 2018 Republicans gained seats though it was midterm year and their party held the presidency. Thus the expected backlash against President Biden’s Democratic Party may not necessarily be a factor in these legislative elections.

In terms of redistricting, Alaska has hit a few roadblocks. The new state legislative maps have been in effect since May 24, but are interim maps. They were created by the Alaska Redistricting Board (made up of three Republicans and two nonpartisan members who voted against the original maps) and are only being used because the original versions were invalidated by the Alaska Supreme Court on grounds of being illegal partisan gerrymanders. The board will continue to work on permanent maps per the Supreme Court’s guidelines in advance of the 2024 election cycle.

Alaska is the most likely of the three states to have a chamber transition to a new majority. Though Alaska’s Supreme Court continues to affirm the right to an abortion under the state’s constitutional protection of privacy, the state Republican Party takes an anti-abortion stance in its platform and may push back on this with greater legislative control.

The state has not enacted any laws changing election procedures in recent years, although that may change if Republicans regain the trifecta. Many bills that would restrict voter access or election administration have been introduced over the past two years, among them one which would end automatic voter registration, end mail ballot elections at the local and state levels, and criminalize most third-party ballot returns.

Voters, however, did push through a ballot initiative in 2020 that eliminated partisan primaries and instituted ranked-choice voting.

Connecticut Senate

The Constitution State’s General Assembly is composed of the 151-member House of Representatives and the 36-member Senate. Currently, Democrats control both chambers, and with a Democrat as governor, the party has the state government “trifecta.”

The contentious Senate is rated Lean D by Cnalysis, which determined that 41 percent of the districts will most likely go to Democrats while 22 percent will most likely go to Republicans, leaving 36 percent as tossups or slightly favorable to one party. In order to flip the House, Republicans would have to win the two Lean R districts, all 7 tossups and the two Tilt D districts, making a Republican majority possible but unlikely.

Sabato’s Crystal Ball rates the Senate as a Likely D, but nonetheless expects the Democrat’s 24-seat margin to be reduced. That expectation matches historical midterm trends for this legislative body. The Democrats lost a seat in both the 2010 and 2014 midterms during Barack Obama’s presidency, and gained five seats in 2018 with Donald Trump in the Oval Office. They have remained in control of the Senate for the past 20 years, except when Democrats and Republicans had equal numbers following the 2016 election. It is likely that they will lose some seats in November, which analysts predict will feature a red wave.

The 2020 redistricting cycle will not have a large effect on the General Assembly elections this year. The new maps were created by a bipartisan commission and were agreed upon by both parties, with Senate Minority Leader Kevin Kelly calling it a “truly bipartisan effort.” According to the Campaign Legal Center, which does not yet have data on the new maps, the previous Senate map had a 5 percent partisan lean towards Republican candidates.

Overall, the mostly likely outcome for Connecticut is the continuation of their long held Democratic trifecta. However, if Republicans manage to beat the odds and win the Senate, the Constitution State will have a divided government. Republicans, even though more moderate than in some other states, would not get far in passing legislation to fit their agenda, but would have increased power to hinder the aspirations of Democrats.

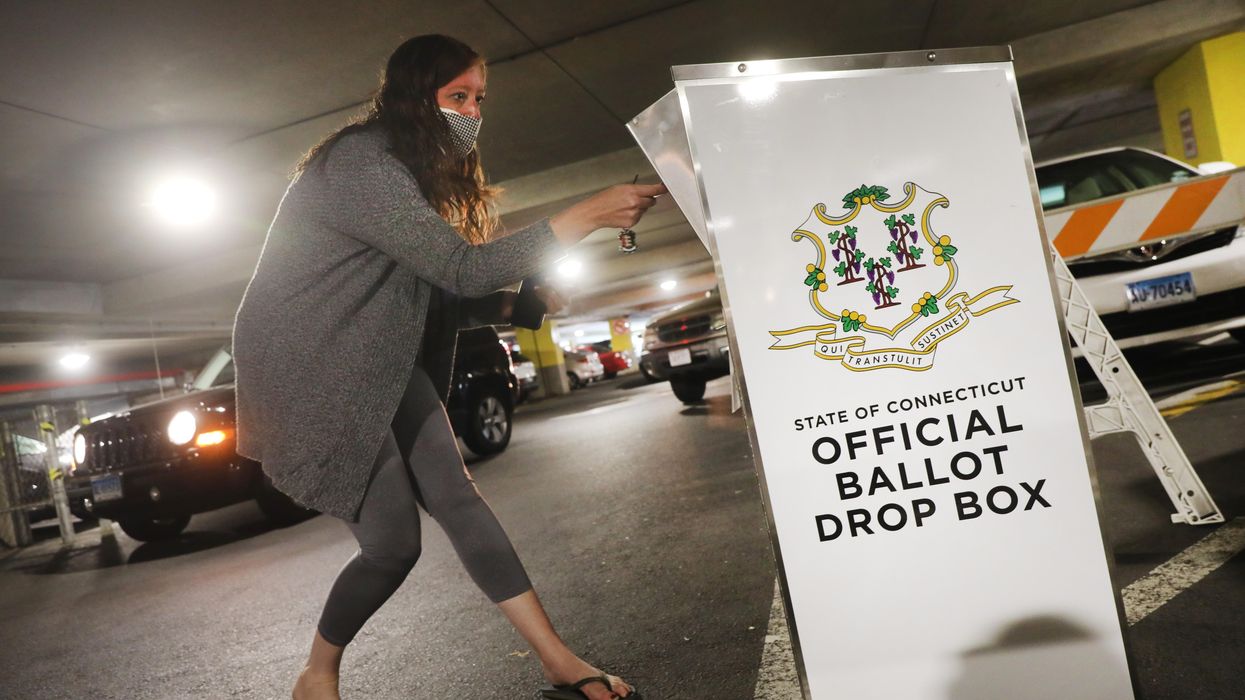

That likely means recent legislative moves to make it easier to vote will stay on the books, but not be further expanded. In recent years, Connecticut has passed a law to restore felons’ voting rights upon their release, made it easier to vote by mail, allowed the use of ballot drop boxes and adopted automatic voter registration.

New Hampshire House of Representatives

The New Hampshire General Court is the fourth largest English-speaking legislative body in the world. The Granite State’s 24-member Senate is dwarfed by its 400-member House of Representatives, which is currently controlled by Republicans, 213–187.

The House of Representatives is rated Tilt R by Cnalysis. But New Hampshire’s unusual system, involving multimember districts, does not conform to Cnalysis’ method of reviewing individual races, according to Director Charles Nuttycombe. Sabato’s Crystal Ball rates this legislative body Likely R, explaining that the firmer Republican Senate majority and Republican governor will aid House Republicans in maintaining and even widening their majority.

The House is historically vulnerable to partisan swings, particularly in midterm elections. From 2004 to 2018 the president’s party has won the House in every presidential election year and lost it in every midterm, according to data from Ballotpedia. Thus historical trends indicate that Republican gains are likely this November. Only in 2020 was this pattern broken, when Republicans won the New Hampshire House despite Joe Biden’s presidential victory.

The 2020 redistricting cycle may also affect results in these elections. While the Campaign Legal Center does not yet have any partisan data for New Hampshire’s state House maps, the previous Senate map was biased towards Republicans. As both legislative chambers and the governor’s seat have been held by Republicans since 2020, the new maps are also likely to be biased towards Republican candidates. (Republican Gov. Chris Sununu has twice vetoed bills intended to reform the redistricting process and form an independent redistricting commission or advisory board.)

Ultimately, though Democrats have a possibility of flipping the House, they face an uphill battle against midterm trends, redistricting and the substantial majority already held by New Hampshire Republicans. Like Connecticut, New Hampshire is currently a trifecta, although one controlled by Republicans. If Democrats manage to flip the House, they will have little power to pass their legislative agenda, but could hinder that of the Republicans.

For example, while abortion is protected up to 24 weeks in New Hampshire and Sununu has said he would not support any further related bills, the New Hampshire House GOP platform states the party supports the “pre-born child’s fundamental right to life,” indicating Republicans may attempt to pass legislation restricting abortion now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned, legislation that a Democrat controlled House could stop.

Additionally, though state Republicans have enacted election-related laws over the past two years that have both expanded and restricted voting rights according to the Voting Rights Lab, the New Hampshire Democrats have highlighted voting rights and fair redistricting processes as priorities. With control of the House, they would likely push those issues but would have to convince Senate Republicans and a GOP governor to go along.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift