With every other vote now counted, and next year's balance of Washington power still in limbo, the wallets of the nation's politically active businesses, advocacy groups and people have opened wide over Georgia.

Next month's paired runoffs will decide partisan control of the Senate, and thereby the limits of President-elect Joe Biden's mandate. So it's little surprise that in the past six weeks they've combined to become the most expensive congressional election in American history.

Nonetheless, the numbers are staggering — and made even more so by the speed at which hundreds of millions of dollars have poured into the state: baskets of checks to the candidates from millionaires, buckets of cash poured in by corporations and advocacy groups, waves of small-dollar online donations, open-ended commitments from the political parties and untold millions more in secretive spending by "dark money" groups.

Nineteen days before Georgians have their say, in other words, their state has already become Exhibit A for the excesses and potential abuses of a wide-open and minimally regulated campaign finance system. And all good-government groups can do is watch, hoping this case study someday helps their aspirations for corralling money's sway over politics.

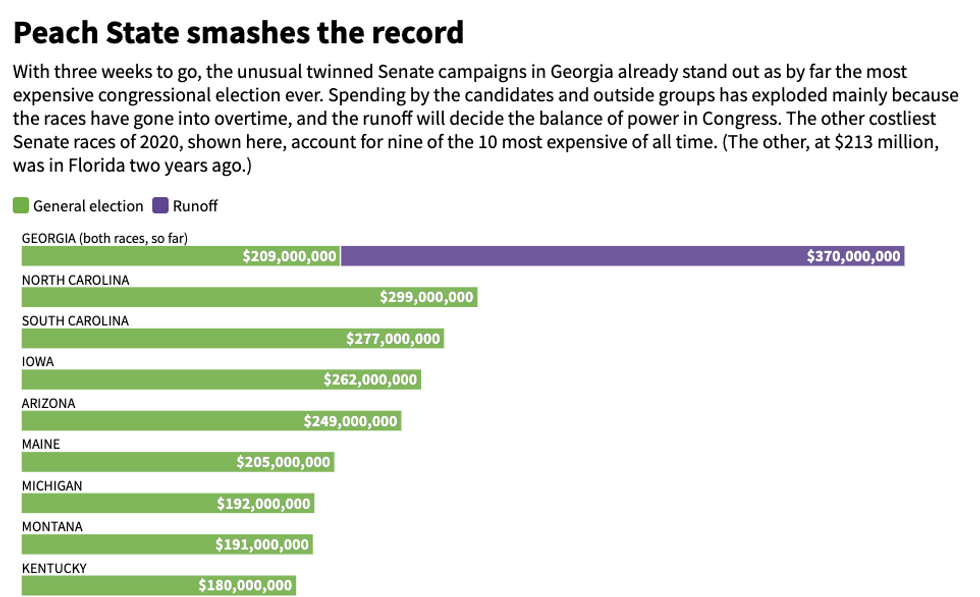

Between the candidates' own advertising buys and outlays by independent political groups, spending on the runoffs alone has already crested $370 million — significantly more than what was spent in any of the other 2020 Senate campaigns, which lasted two full years. Nine of the 10 most expensive Senate races in history were this year, according to an analysis by the Center for Responsive Politics, and even before the runoffs the Georgia contests would have combined to make the list with a $209 million spent.

Sources: Center for Responsive Politics, Federal Election Commission

Sources: Center for Responsive Politics, Federal Election Commission

"Voters across the political spectrum are sick and tired of the amount of money in politics and the way that wealthy donors have their voices heard louder than everybody else," said Brendan Fischer, director of federal reform at the Campaign Legal Center. "It's about time that politicians start to act on voters' wishes."

The only chance of that happening in the next two years, though, is if both challengers are rewarded for their astronomically costly efforts.

Victories by Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock on Jan. 5 would result in 50 Democratic senators in the new Congress — a bare majority, because they would have guaranteed tie-breaking help from the new vice president, Kamala Harris.

And along with their fellow Democrats still in charge in the House, that would mean the power to at least partly advance the Biden agenda, where democracy reforms have been promised but not yet raised to prominence.

Victories by either Republican incumbent, David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler, would mean a divided Congress with the Senate still under the control of Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who rose to the leadership in the 1990s largely because his colleagues appreciated his dogged and largely successful efforts to kill campaign finance legislation.

The ocean of political money

Two weeks before the general Election Day, the last time the candidates had to provide detailed accountancy of their finances to a largely neutered Federal Election Commission, the four candidates had raised a combined $101 million — with documentary filmmaker Ossoff the leading recipient, at $33 million since his campaign began.

It's not clear just how much more they have raked in since, because their next FEC reports are not due before Christmas Eve. But the enormity of their hauls are partly revealed in reports already filed by the two parties' online fundraising platforms, ActBlue and WinRed.

The 24-hour drumbeat of email solicitations from ActBlue led Warnock, who is the pastor of Atlanta's historic Ebenezer Baptist Church and would become the state's first Black senator, to collect $57 million in the first three weeks of the runoff, more than double his individual contribution total from the entirety of the campaign before Election Day. Ossoff raised $55 million in online donations in the same time, nearly double what people gave him before Nov. 3.

Perdue had collected $28 million through WinRed, swamping his $11 million in individual contributions for the general election. But Loeffler, who had to fight for Republicans' money against her rival GOP Rep. Doug Collins before the first round of voting, realized the biggest gain — a nearly ninefold surge in her haul from individuals by raising $27 million in the three weeks after making it to the runoff.

And the new totals do not reflect checks that have come in during November and December, which is generally how well-healed donors deliver their money. The giving limit for a general election is $5,600; if there's a runoff, an individual can donate $2,800 more. (The second rounds are required because Georgia requires statewide winners to receive more than 50 percent of the vote, which happened in neither Senate race Nov. 3.)

The candidates are hardly acting in a vacuum. Party committees, special interests and other organizations have already poured $143 million into the runoff — on top of the $128 million they spent before November. As in almost all congressional contests with such enormous national consequences, most of the money is coming from groups outside the state. And, if past is prologue, tens of millions more will arrive in the final weeks.

Securities and investment businesses, real estate enterprises, the insurance business and law firms have been the most heavily invested in Loeffler and Perdue — contributing a combined $5 million. The law and Wall Street sectors have also given the most to Ossoff and Warnock, and along with the worlds of education, health care and government employee unions the combined total tops $11 million.

So-called super PACs, political action committees permitted to raise and spend unlimited amounts to sway elections so long as they disclose their donors, have also been spending big. The Senate Leadership Fund, McConnell's main political arm, has allocated $68 million to the re-elections of his two colleagues. The Senate Majority PAC, the parallel organization of Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, has spent $33 million to aid his would-be colleagues.

But it's not nearly so clear where much of the money has come from. The Center for Responsive Politics says almost $9 million, or 3 percent of the total spent independent of the candidates, has come from "dark money" groups that don't have to disclose the origins of their political giving. Most of these groups care less about specific industries than about ideology.

"It's the American people who will lose as a result of all this secret spending," said Michael Beckel, the research director at Issue One, which advocates for more campaign finance regulation.

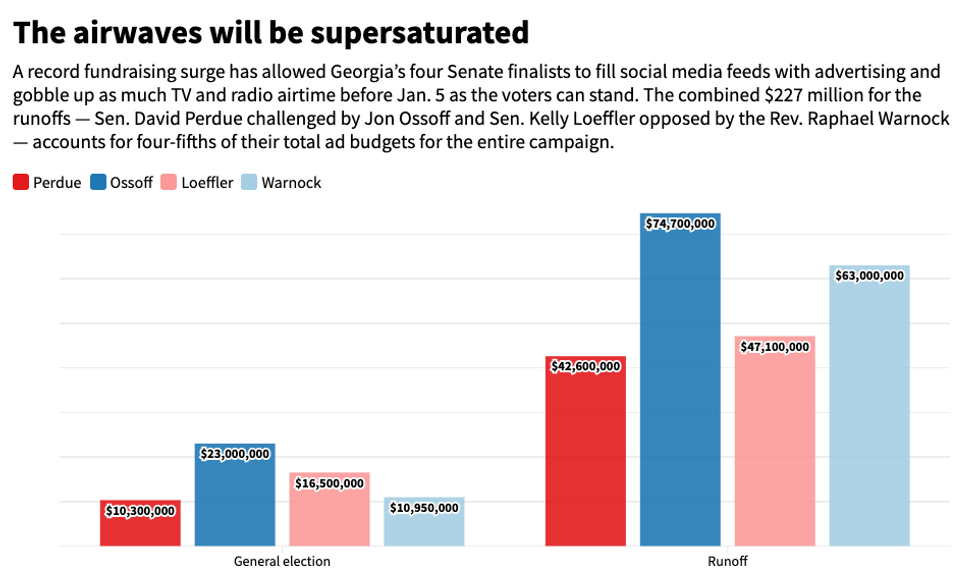

While outsiders have been spending on their own advertising and get-out-the-vote efforts, the coffers of the candidates have been getting tapped mainly to support an onslaught of ads — worth more than $227 million as of last week, according to AdImpact, a firm that tracks such spending. The vast majority has been allocated to blanketing the TV airwaves, even though research suggests more and more voters are paying most attention to the much-less-expensive ads they see online.

Sources: Federal Election Commission, AdImpact

Sources: Federal Election Commission, AdImpact

Both Google and Facebook had blocked political ads from their sites to tamp down on the spread of misinformation ahead of Nov. 3, with the presidential election at the forefront of their decision making. But the companies recently lifted their bans for the Georgia Senate runoffs, meaning candidates and outside groups can once again push their messaging on those platforms.

Spend now, reform later

Wins by Ossoff and Warnock would not only give campaign finance bills at least a theoretical shot at consideration, but also mean the arrival at the Capitol of two more outspoken critics of the system they're for now relying on.

Both have pledged not to take money from corporate political action committees. It's a popular promise from Democratic congressional candidates, because it allows them to signal that their loyalty lies with voters and not wealthy special interests — but at a minimal cost, because there's so much other money available to them from ideological special interests on the left.

In high school, Ossoff interned for the late Rep. John Lewis of Atlanta, the iconic embodiment of voting and civil rights. Several of his investigative documentaries have sought to hold powerful institutions to account. And Ossoff now has the distinction of being a candidate in both the most expensive Senate race and the most expensive House race of all time. (More than $48 million was spent overall on a 2017 special election to fill a suburban Atlanta congressional seat, a contest he narrowly lost.)

"As long as money buys political influence, our government's policies will favor the most powerful special interests," his campaign website says, and it says tighter money-in-politics rules are essential to restoring the nation's "prosperity and competitiveness."

Warnock's democracy reform focus has been mainly about expanding access to the ballot box. Through his church and as former chairman of the New Georgia Project, the voter registration campaign started by 2018 gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, he has worked to boost Black turnout and condemn perceived suppression efforts. His campaign platform includes revitalizing the Voting Rights Act, expanding early in-person and vote-by-mail options and making Election Day a federal holiday.

The Republicans now stand as two of the richest members of the Senate, and neither has deviated from party's orthodoxies including opposition to new campaign finance regulations and any further federal control over election rules.

Perdue is seeking a second term after a career as a corporate turnaround artist with time as CEO of both Reebok and Dollar General. Loeffler, appointed last year when Republican Johnny Isakson resigned because of failing health, may be the wealthiest senator of all after amassing a financial services fortune estimated at $800 million. (She's already given her own campaign $23 million.)

Both have come under scrutiny for their stock trades, which suggested they may have benefited from insider knowledge afforded them as senators — of industries and potential shifts in government policies, especially related to the coronavirus pandemic. They have denied wrongdoing and the Justice Department has reportedly decided against prosecuting them.

Every vote will matter

Polling suggests that both Perdue vs. Ossoff and Loeffler vs. Warnock are genuine tossups — so the winners will be from whichever side motivates more of its most passionate supporters to cast a ballot.

Biden claimed the state's 16 electoral votes by a margin of just 12,000 out of 5 million votes cast in the fall, turning the state blue for president for the first time in 28 years, while Ossoff came within 88,000 votes (2 percentage points) of upsetting Perdue. The different rules for the special election for the other Senate seat drew 19 candidates from all parties. The top Republicans, Loeffler and Collins, got a combined 46 percent. Warnock and his two main Democratic opponents took 45 percent.

With absentee ballots pouring in and early voting having started Monday, more than 914,000 people have already voted — including 24,000 who did not vote in the general election.

Turnout has not topped three-fifths of the general election number in any of the previous four Georgia runoffs since 1992, though, so it would be notable if more than 3 million ballots are cast overall.

If that is the total number of votes, then $123 has been spent — already — for every one of them.

Why does the Trump family always get a pass?