First it was Russia, relentlessly launching cyber salvos at the ramparts guarding our precious election systems four years ago. Then it was the coronavirus pandemic that swept across the country and threatened to derail the engine that drives our democracy.

And now it's the once-revered Postal Service that is taking its turn on the national stage as the bogeyman who will destroy a presidential election.

But a closer look at the problems involving mail-in ballots during the primary election season, from small-scale mishaps to near disasters, shows that some of the blame surely rests with the USPS — but much of what's gone wrong is the fault of others.

Parsing blame for the balky story of election mail this year is sure to be a feature of a Senate hearing Friday. Postmaster General Louis DeJoy has been summoned to explain policies that good-government groups, state officials and congressional Democrats suspect are designed to cripple the Postal Service so it can't execute its vital role in the election.

Last month USPS warned election officials in 46 states that their deadlines for requesting and returning absentee ballots were "incongruous" with the current state of mail service and that voters who act close to the cutoffs risk being disenfranchised. After 21 states announced plans to sue, DeJoy on Tuesday shelved until after the November contest a range of service reductions, his suspension of overtime, shutdowns of sorting machines and the removal of public mailboxes. Several voting rights groups sued anyway.

An ocean of mail, even without ballots

One thing that is clear about the coming election is that the scale of change in the way people vote will be unprecedented. And the Postal Service will be right in the middle of everything.

Four years ago, according to the Election Assistance Commission, 33 million Americans voted by mail — 23.5 percent of all the ballots cast. The outbreak of the coronavirus, which has infected 5.5 million Americans and killed more than 170,000, has caused the share of votes cast by mail in the primaries to double or triple in states that didn't switch to all vote-by-mail.

The pattern looks to continue for the general election. So if three-quarters of all votes move through the mail this fall, and turnout is the same as 2016, that would mean more than 100 million ballot envelopes have to make their way from an election office to a voter — and back again.

That number is huge, but it is dwarfed by another number: 182 million. That is the number of pieces of First Class mail the Postal Service handles on a typical day.

So, it is not surprising that while lots of people are panicking, officials with the USPS claim they have plenty of capacity to handle the extra volume.

"There is not going to be an impact on service," Justin Glass, director of the agency's election mail operations, flatly promised during a meeting with Ohio election officials this month.

Worry about whether USPS could fulfil its central role in the democratic process began in the runup to the Wisconsin primary in April, the first full-scale election to go forward on time after Covid-19 took hold. Legal battles over how the election would be conducted went all the way to the Supreme Court. They were still going on just hours before the polls opened — and alleged problems with mailed ballots became a focus of attention thereafter:

- Three tubs of absentee ballots from Appleton and Oshkosh were found at the USPS processing center in Milwaukee after polls closed.

- About 2,700 absentee ballots requested March 22 and 23, two weeks before primary day, were not delivered in time to be used.

- The Postal Service returned absentee ballots to the Milwaukee suburb of Fox Point (where 2,800 votes were cast) three weeks before the election without explaining why they were returned and not delivered.

Investigators for the independent inspector general for the USPS said the three tubs were not delivered by a contractor until two hours before the polls closed. So not the post office's fault.

Confronted by complaints from voters about not receiving their absentee ballots on time, the Milwaukee Election Commission blamed itself for a "computer glitch." Again, not the post office's fault.

As for the ballots returned to Fox Point, the postal carrier didn't pay enough attention — and that was aggravated by the fact that the ballots were incorrectly addressed. So, that one was partly the post office's fault.

The inspector general's report also pointed to some broader, national problems — concerns that have turned out to be prophetic as the primary season has rolled along with more and more people voting by mail.

Tight deadlines, not set by the post office

A key concern, pointed out in the report, is that 24 states set deadlines for people to request absentee ballots just six days or fewer before Election Day. Eleven of those states allow the request within three days.

Even if a state or county pays for roundtrip First Class service, which has a standard delivery window of two to five days, the completed ballot still might not be delivered on time — in part because it usually takes a day or two to process an absentee ballot application, according to elections expert Tammy Patrick of the Democracy Fund, a foundation that supports easier voting.

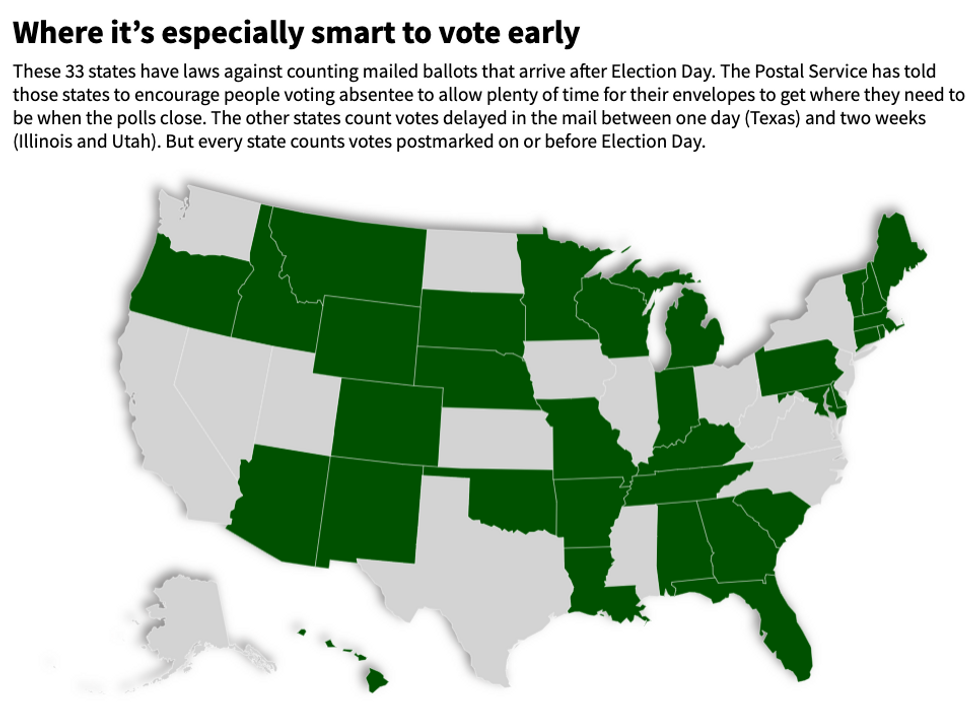

About two-thirds of the states reject ballot envelopes that arrive after the polls close on Election Day. Some have relaxed that deadline because of the pandemic, but all states still require ballots be postmarked by Election Day.

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures

Three weeks after the Wisconsin disaster, an Ohio primary that was switched to most-by-mail because of Covid-19 again focused attention on the Postal Service because of reports people did not get their absentee ballots in time to return by Election Day.

GOP Secretary of State Frank LaRose urged the state's congressional delegation to pressure USPS to do better in a letter saying "we have heard wide reports" of delays in delivery but offering no specifics. Postal officials promised extra vigilance with election mail but did not concede there was a widespread problem with delivery.

And, later, LaRose acknowledged a contributing factor in ballots arriving late was the narrow window of three days between the deadline for asking to vote by mail and returning a finished ballot. He called that "logistically impossible" — but so far the law has not been altered for November.

A month after Ohio, Maryland had its share of problems with absentee ballots arriving on time. But officials concluded the blame lay mostly with the vendors who printed and mailed them — and so they switched vendors.

The list goes on. California, which allows ballot requests until a week before an election, disqualified more than 100,000 absentee envelopes in the March primary mostly because they arrived after the deadline, had no signature or the handwriting didn't look enough like what was on file. In Connecticut, the delivery of 20,000 absentee ballots was delayed until the last minute because of miscommunication between town clerks and the secretary of state's office.

The customer's not always right

Other sources of problems with absentee ballots that are not the fault of the Postal Service include:

Sloppy voter rolls. Poor record-keeping can cause absentee ballots to be sent to the wrong address, or for people never to receive a ballot or an application for a mail-in ballot in states that make a rapid switch to proactively mailing a ballot or a request form to every registered voter.

In Las Vegas, for example 223,000 ballots mailed out for Nevada's first all-by-mail primary in June were returned as undeliverable — largely because ballots were sent to everyone on the county's voter list, including inactive voters, many of whom had moved. For the fall, the state is sending ballots only to people who have voted in recent elections.

Poor ballot design. Printing return envelopes that do not conform to Postal Service design standards can mean significant delays or mishandling. USPS offers design help to make sure the ballots can properly go through the automated processing system and receive a postmark — vital for validating that the vote got cast by deadline.

Bad handwriting. Ballot envelopes that voters forget to sign, or have a signature that doesn't look like the handwriting on the registration form, are tossed without being opened in 31 states. (The others have processes for allowing voters to fix, or "cure," their mistakes.)

In Louisville, signature problems were behind more than half the 8,000 absentee ballots that were tossed out in the Kentucky primary. In Vermont this month, at least 6,000 absentee ballots were rejected because people failed to properly follow the directions. Many were tripped up by the fact that the state allows voters to obtain a Republican, Democrat and Progressive primary ballot — so long as they complete just one and return it with the other two blank forms. Those who filled out more than one ballot, or forgot to return the others, had their votes invalidated.

Saving on stamps. Many ballots do not arrive on time because some election officials decide they have to save the taxpayers money by relying on the cheaper but slower mass marketing designation instead of first class mail.

Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer recently accused the Postal Service of trying to price gouge some states and counties because the agency suggested they should switch to the faster, more expensive designation. Postal Service officials responded that they were just trying to improve the chances that absentee ballots arrive on time.

Clearly, there are instances where the fault lay with postal workers.

In New York, for example, thousands of mailed-in ballots originally were rejected because they lacked postal marks showing the date they arrived. According to testimony in a federal lawsuit attempting to reinstate those votes, election officials met several times with Postal Service managers to emphasize the importance of postmarking the ballots so those that were marked by Election Day would be counted.

And next door in New Jersey, people snapped photos of packets of absentee ballots that were piled in apartment building lobbies and not distributed to the correct addresses within the building.

In the past few days, however, almost all the attention to the Postal Service has focused on President Trump's attitudes toward mail-in voting; his sometimes wavering hard line against propping up the pandemic-hobbled mail system with as much as $25 billion in time for the election; and the actions of DeJoy, a major GOP donor with no postal experience installed in the job by the president two months ago.

The postal service inspector general said in a report last year, before DeJoy took over, that the ''Postal Service has not met the majority of its service performance targets over the past five years."

Despite all these concerns, numerous voices in and outside the Postal Service have said the agency has the capacity to successfully handle the huge increase in mail-in ballots this fall.

The conservative R Street Institute think tank, for example, published a report about the Postal Service last month concluding it "has proven capable of reliably moving government documents for decades. Accordingly, there is little question that, as it has done so many times in the past, it will rise to the occasion ... and deliver."

In his first open meeting with the Postal Service's board of governors two weeks ago, DeJoy said that the operation "has ample capacity to deliver all election mail securely and on-time, in accordance with our delivery standards, and we will do so."

After the hearing Friday before the Homeland Security Committee in the Republican-controlled Senate, DeJoy will appear Monday before the Oversight and Government Reform Committee in the Democrat-controlled House.

Trump needs to get ready for the blowback