This presidential election year, Americans need solutions so they don't have to choose between protecting their health and exercising their right to vote.

On Tuesday morning polls will open for primaries in eight states and Washington, D.C., and election officials are making final preparations to keep voters and election workers safe. Contests in four of those states were postponed during the coronavirus pandemic, which is why the day is being labeled as another Super Tuesday.

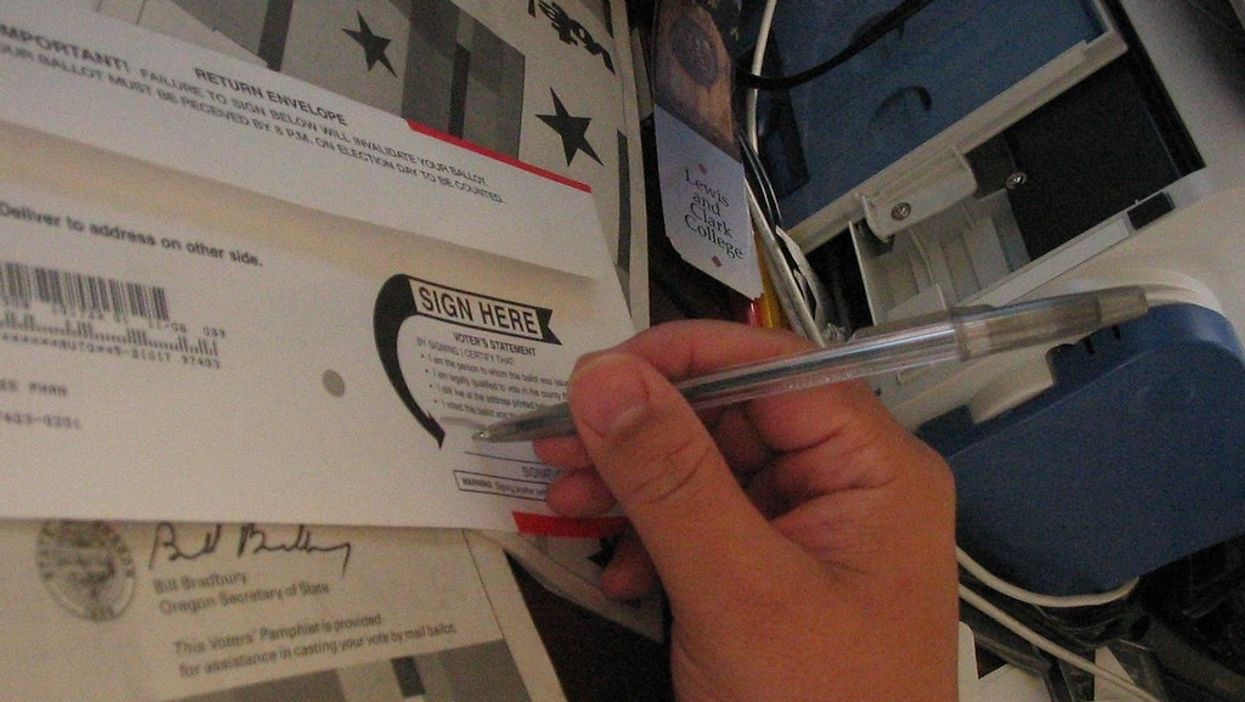

And so this is an important moment for a closer look at states that already vote by mail. My home state of Oregon is ranked first: 99 percent of us voted from home in the 2018 midterm election, more than any other state.

To be clear, voting by mail is not every voter's best option, so it's important to provide alternatives and assistance. Oregonians can also pick up a ballot in person. If they're temporarily serving in the military or otherwise living overseas, they get their ballot early enough to return it. Those with visual impairment can use their own assistive computer devices to fill out their ballot. Regardless, when every registered voter is sent a ballot well in advance, with postage-paid return, this greatly expands access.

As executive director of Common Cause Oregon, I've been watching as many other states have struggled to hold safe and fair elections for citizens during the public health crisis. And I realize how fortunate Oregonians are to live in a state that has been voting almost entirely by mail for two decades.

Last week, Oregon held its presidential, congressional and state primaries on schedule and without the problems we've seen elsewhere during the Covid-19 outbreak. Turnout was among the highest among the 30 states that have already held primaries this year.

[See how election officials in Oregon — and every other state — are preparing for November.]

There are many issues that divide Americans, but when it comes to a public health crisis and our right to vote, we should leave the partisan politics behind.

President Trump himself has voted by mail in three elections since 2017. But somehow he doesn't believe other Americans should be able to — because he is more interested in playing political games than ensuring every eligible American can vote in a safe, fair and accessible way.

Here are the facts:

Vote-by-mail is a paper-based system that is not hackable and can easily be audited to ensure the election results are correct.

It has been tried and tested in states across the country and has proven to be a secure and convenient option for voters to make their voices heard.

It has been endorsed by leading Republican officials from across the country — including Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah, Gov. Mike DeWine of Ohio, Gov. Larry Hogan of Maryland, Gov. Pete Ricketts of Nebraska and Secretary of State Kim Wyman of Washington.

Oregon started experimenting with vote-by-mail back in the 1980s. A referendum put on the ballot by citizens in 1998 was approved with 69 percent support, making Oregon the first state to conduct all its elections almost exclusively by mail. Washington, Colorado and Utah have since joined us, and Hawaii is doing so this year.

When I first moved to Oregon 30 years ago, the state was already conducting some elections by mail. At the time I was in my twenties and had voted previously in another state — the "old fashioned" way. I was struck by the difference. No need to take time off from work, track down my polling place or stand in long lines. My ballot came to me.

Now Oregon votes almost entirely by mail, with in-person alternatives for those who need them. Coupled with modern voter registration systems — including online registration and automatic registration for eligible people who interact with the state's department of motor vehicles — our voting system has helped keep Oregon elections secure and efficient, with among the highest participation rates in the country.

As Oregon moved toward full vote-by-mail in 2000, Republicans and Democrats took turns supporting and opposing it — each temporarily convinced it worked in favor of one party and then the other. Ultimately, though, vote-by-mail favors voters, not parties, and all Oregon political parties have come to support it.

Nationwide, 25 percent of us already vote by mail. Just this year, at least 16 states have postponed elections or moved to conduct them by mail to ensure voters can cast ballots from the safety of their homes. Considering the public health crisis, every state has the power to expand some vote from home option, such as mail-in absentee ballots.

Oregon's Ron Wyden, the first senator ever elected in a vote-by-mail contest, and fellow Democrat Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota are pushing a Senate bill that would require every state to allow all voters to vote by mail — or at polling sites for at least 20 days before Election Day. Those are just two of the common-sense solutions to the challenges of holding elections affected by emergencies.

The April primary in Wisconsin, where thousands were forced to choose between their health and their right to vote, shows why we need state and local officials to take responsible action now to expand voting rights. There is nothing partisan about ensuring full voter turnout.

Expanding vote-by-mail is imperative during this pandemic. We must scale up our existing programs now while we have time to preserve our ability to vote in the November general election.