Our democracy has just emerged from a stress test unlike any other in our history. Despite the fears of many, and thanks to heroic efforts by election administrators amidst a pandemic, there will be a peaceful transition of power on Jan. 20. The American experiment endures.

But while the election has been settled — and most recently affirmed by the Electoral College on Monday — our divisions remain intense. We are a polarized nation of red and blue. We are cleaved along geographic, generational, racial and education lines. Our political and cultural identities have become one. History shows us that these are the dangerous fault lines that tear many nations apart for good.

How fractured are we? No one wants to hear this, but Joe Biden carried Wisconsin, Arizona and Georgia by just a cumulative 43,000 votes. If only that tiny number of ballots had gone to Donald Trump instead, the two would have tied at 269 electoral votes each.

The Senate could well end up knotted at 50 from each side if Democrats win both January runoffs in Georgia, a state Biden narrowly carried. The House looks nearly as close, with at most seven seats — less than 2 percent of them — making the difference between Speaker Nancy Pelosi or Speaker Kevin McCarthy.

We have an urgent need for structural reforms that might change the electoral incentives that help us repair the dysfunction and mistrust that grip our politics. One of the very best solutions would be ranked-choice voting, which turns out to be something that Americans already agree on: It appeared on the ballot in eight places nationwide this year and won a resounding seven victories.

Indeed, there might not be any electoral reform with more momentum. Maine and Alaska will now use ranked-choice voting for nearly all elections in the wake of November's ballot measure win in Alaska. Next year, it arrives in New York as the city chooses its next mayor. Earlier this year, five Democratic presidential primaries used RCV to help voters negotiate a ballot with a dozen candidates. And Republicans in Utah, Indiana and Virginia employed the system to determine congressional and statewide office nominees and party leaders.

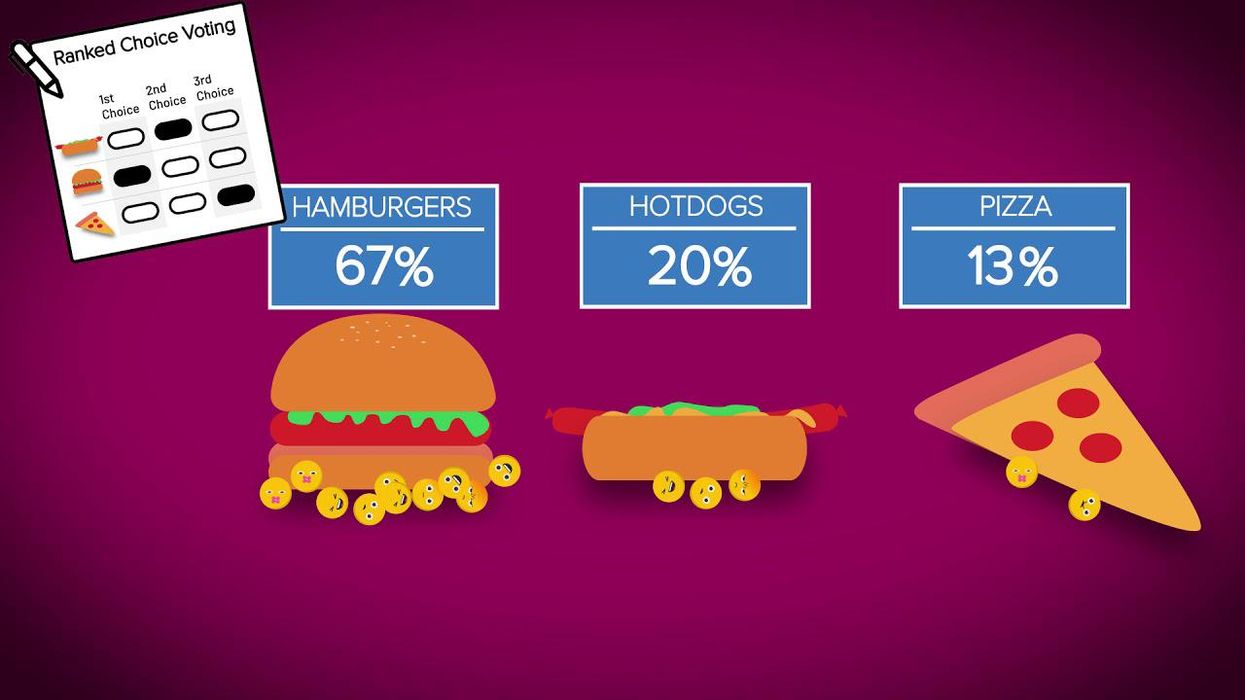

Ranked elections work by mimicking an instant runoff. Voters get the power to rank their choices for each position in order. Candidates who are the first choices on at least 50 percent of ballots are the winners — like any other election. But if no one gets a majority of No. 1 votes? The person with the fewest No. 1 nods is eliminated. The second-choice votes of those who liked the last-place finisher the best are counted instead. The process continues until one candidate is revealed to have support from most voters.

The ballot speaks for the voter. Candidates can't win with shallow base support any longer.

More candidates can run, without any of them being derided as a spoiler. Voters can consider all of those candidates, without worrying they might waste their single vote. Politicians need to reach out to everyone, not just their base, and when that happens voters are more likely to listen.

Ranked-choice voting changes the incentive game completely: Voters are more satisfied, campaigns are more positive and our frozen political coalitions become more flexible.

Voters are catching on. Besides the major victory in Alaska, voters also approved ranked-choice voting this year in all six cities that considered it — in California, Colorado, Maine and Minnesota. These municipal ballot measures were approved by nearly two-to-one, on average, and were embraced by voters for many reasons. Some appreciated the greater choice. Others recognized it as a faster and cheaper way to handle runoffs. The one time RCV was rejected, a statewide ballot initiative in Massachusetts, the idea was nonetheless supported by nearly four-to-one among voters younger than 30, demonstrating that millennials and Generation Z are hungry for more choice.

Our system is ridden with structural unfairness. Those realities aren't going away, either. Our goal right now needs to be finding ways to make our elections fairer in a way that voters and candidates can support, no matter their political beliefs.

This year was a lonely one. Not only were we struck by a pandemic, but we also felt mistrust for our fellow citizens. But it doesn't have to be this way. A reform as simple as letting people vote with nuance and back-up choices would be a key step towards building a bridge back to a more unified nation.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift