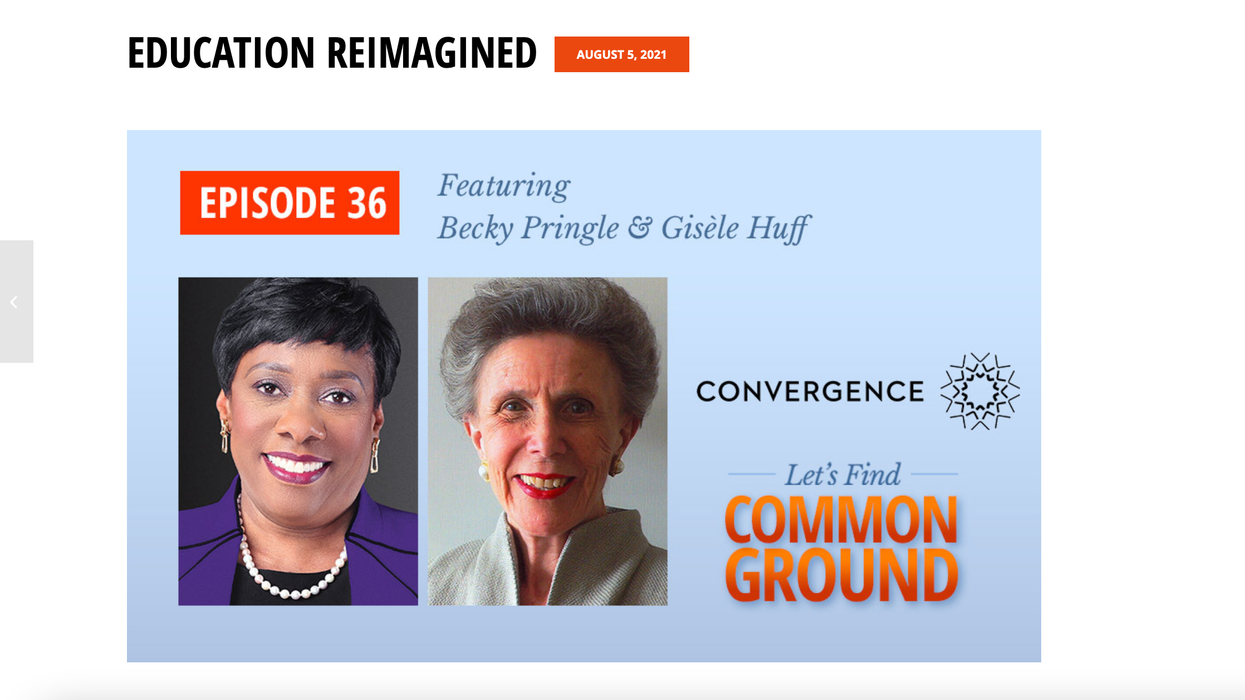

Everyone wants the best education for their children. But parents and teachers don't always agree on how to get there. In this episode of the Let's Find Common Ground podcast, two education leaders discuss a transformational vision for U.S. education. Dr. Gisèle Huff is a philanthropist and longtime proponent of school choice, including charter schools. Becky Pringle spent her career in public education and serves as president of the National Education Association, the nation's largest labor union. This podcast was co-produced in partnership with Convergence Center for Policy Resolution and is one of a series of podcasts that Common Ground Committee and Convergence are producing together. Each highlights the common ground that resulted from one of Convergence's structured dialogues-across-differences.

Podcast: Education Reimagined