Traditionally, voter registration and turnout drives go right for the moral argument.

Registering to vote and going to the polls is your obligation in a democracy, the organizers plead. People have died to make it possible for us to vote. And, of course, every vote counts so yours could decide the election.

Noble thoughts, all, but the relatively poor turnout through the years — including just north of 30 percent of voters ages 18 to 29 in last year's hard-fought midterm — argues for a different approach. Maybe one as truly American, if in a totally different way, as the appeals to duty and civic pride.

Think teams. And competition. And, best of all, prizes.

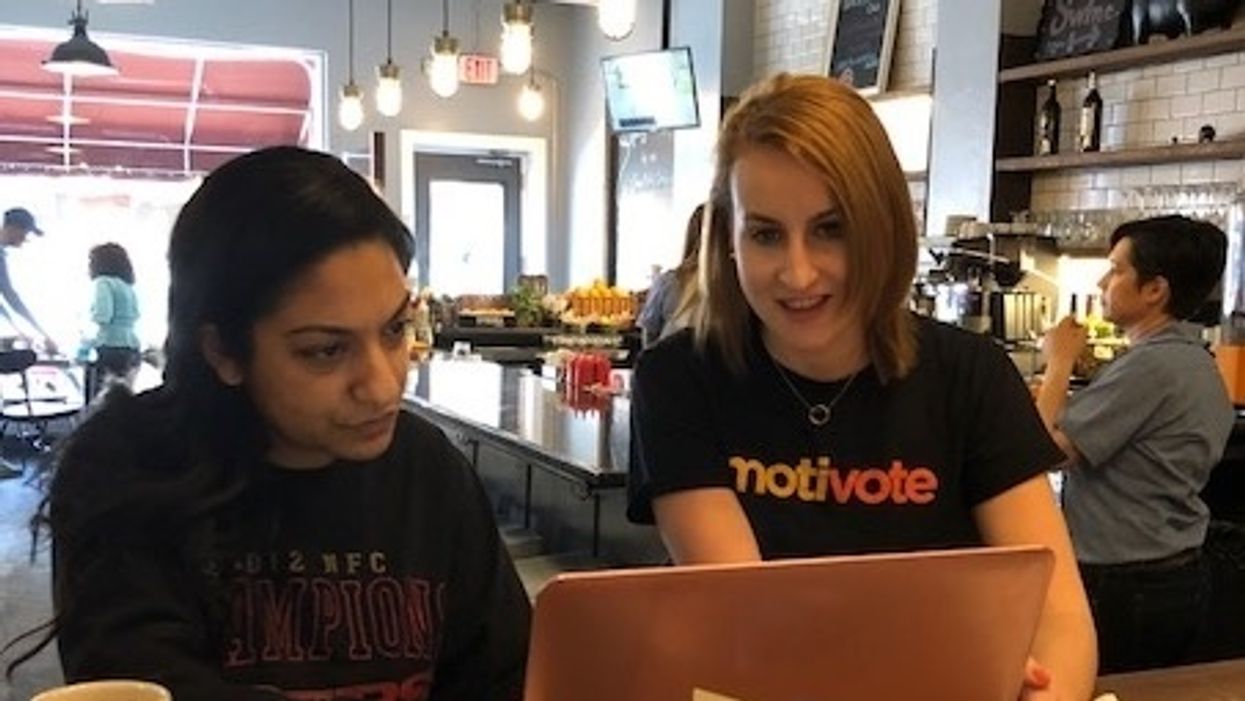

This out-of-the-box strategy is the brainchild of graduate school classmates Jess Riegel and Rachel Konowitz. With their fledgling venture Motivote, they hope to put an unusually youthful stamp on the electorate in some off-year contests this fall but especially in the coming presidential election.

Riegel studied political science at the University of Pennsylvania and was then assigned by Teach for America to schools in New Orleans and Newark, N.J. Konowitz worked as a student organizer on issues including voter registration but grew frustrated with traditional methods, such as door-knocking, that never seemed to move the needle much.

Armed with their millennials' native knowledge of social media, an understanding of behavioral economics from their graduate work as well as their own research, the pair put together a business plan particularly focused on getting younger people to vote.

What began as a capstone project for master's degrees in public administration at New York University became their passion and now their jobs.

"It's very easy to say that young people are apathetic," Riegel said. "But really, it's understanding voting as a behavior and what is getting in the way of socially conscious, politically opinionated young people from voting."

What they found is that a series of seemingly insignificant obstacles — what they call "micro-barriers" — end up causing plenty of people either to never get registered to vote, or to not follow through with their desire to cast a ballot even once they are registered.

While conducting a research and development phase after some preliminary Motivate testing during last fall's midterm campaign, Riegel and Konowitz said, they were struck by what has become a seminal essay on millennial burnout by Anne Helen Peterson published in January. It begins with the story of a young man who never registered to vote because thoughts of filling out and mailing in the form filled him with anxiety.

To Riegel and Konowitz, this sounded a lot like what happens when people intend to start a diet or an exercise program but fail to follow through.

To overcome these hurdles, the two created an online program that breaks down the voting process into bite-sized actions and uses a series of "behavioral nudges" to get people to the finish line. Participants become part of teams, perhaps all the men in one college fraternity class or all the women sharing a group house, to create additional competition and peer pressure for getting the mission accomplished.

Points are given for completing tasks and prizes doled out.

"At the core of what we are doing is creating social accountability around following through to vote," Riegel said.

For the prizes, such as gift cards, Motivote reaches out to businesses looking to promote young people voting.

And since it is a business, Motivote charges a licensing fee to groups that use the system.

Currently, Motivote is working with the group Mississippi Votes to create teams on 11 college campuses in preparation for the state's hotly contested 2019 elections for governor, other statewide offices and the Legislature.

The company is also planning to work with an African-American voting group on the Memphis municipal elections, with Mi Familia Vota in time for the Houston city elections, and with several groups in Virginia in advance of its General Assembly and local elections.

Its successes and setbacks in these contests will help refine the company's motivational strategies in time for the 2020 presidential contest, when both nominees are sure to be playing close attention to turning out younger people.

Motivote stays on the right side of election law by not providing prizes for actually voting but for the steps leading up to act of casting a ballot.

And how does the company know its success rate, as measured by the number of people its targeted who actually vote? Participants are asked to post a selfie from their polling place afterward.

As for the potential criticism that Motivote's methods infantilize young voters and trivialize the most sacred of civic responsibilities, Riegel has this emphatic rebuttal.

"This is too important to just keep throwing money into things that don't work," she said. "It's not how many doors I knock on. It's not how many texts I sent. We kind of glorify those metrics but that's not connected at all to how many people actually vote. That's what we are driving for."

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift