Johnson is the dean and professor of public interest law and Chicana/o studies at University of California, Davis.

Immediately before the Supreme Court's summer recess each year, it releases decisions in some of its most challenging and significant cases.

This year was no different.

On June 27, the last day of the term, the Supreme Court decided Department of Commerce v. New York, a case exploring legal issues surrounding the addition of the question, “Is this person a citizen of the United States?," on the 2020 census.

The decision is of great practical importance, as the final numbers generated by the census will affect representation in Congress, allocation of federal dollars and much more. The political implications of the citizenship question made the case politically volatile and controversial.

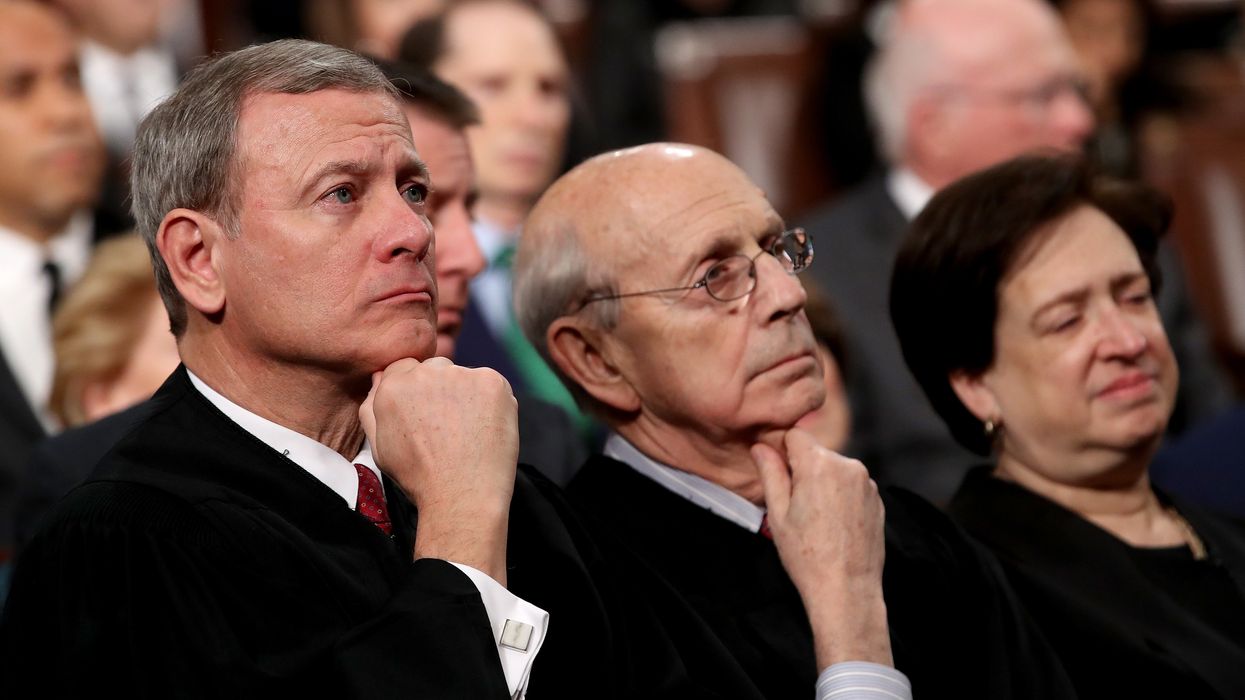

In an opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts, the court chose not to accept what may well be the Trump administration's pretext for the citizenship question to mask partisan political and discriminatory motives.

As a scholar of immigration law and civil rights, I was not surprised by the outcome. The court decided the case in a way that will help maintain its legitimacy in the future.

Census influence

Because the census is conducted only once every 10 years, it can affect close to a generation of policies.

By influencing electoral districting, the census can affect political representation in Congress, as well as the relative numbers in Congress from the two major political parties. That, in turn, affects how federal money is spent and which groups and programs are preferred or disfavored. Put simply, the census has dramatic political impacts on the entire nation.

In 2018, Wilbur Ross, the secretary of Commerce under President Trump, announced that the Bureau of the Census intended to add a question about U.S. citizenship in the form sent to all households in the 2020 census. The proposed question would in fact be a readdition, because some form of that question had been in census questionnaires in the past.

The Trump administration said that the citizenship question would improve enforcement of the Voting Rights Act, which protects the voting rights of citizens. However, opponents claimed that the question was motivated by partisan political considerations, including voter suppression and an effort to systematically undercount immigrants, particularly Hispanics.

In an ideal world, a count of noncitizens could be beneficial to policymakers and researchers.

For example, a city could use the number to establish a need for resources to facilitate naturalization and other immigrant services. States with large immigrant populations would know about how much federal funding was needed to cover immigrants' costs incurred in public education and English as a second language courses.

However, civil rights groups and immigrant rights activists were concerned that, especially with President Trump at the helm, a citizenship question would discourage immigrants from participating in the census, for fear that answering the question truthfully might lead to their removal from the country by the very administration collecting the data.

If that turned out to be true, immigrants might well be chilled from participating in the census. The result would be an inaccurate – and low – count of immigrants.

The decision

The court held that the proposed citizenship question does not violate the Constitution, which vests broad discretion in the U.S. government in deciding how to conduct the census.

They also ruled that Ross' decision did not violate the Administrative Procedure Act. This act requires that certain procedures be followed in administrative decisions and that agency officials offer reasoned and rational explanations for their decisions.

However, Roberts, in a part of the opinion joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, ruled that the Department of Commerce needed to provide further explanation for adding the question. The court said that the Department of Commerce's claim that the citizenship question was solely designed to help Voting Right Act enforcement seemed “contrived."

The chief justice further wrote that, “Our review is deferential, but we are 'not required to exhibit a naivete from which ordinary citizens are free,'" quoting legendary Judge Henry Friendly.

Some court observers were surprised by the outcome.

After oral argument in April, some had predicted that five justices favored the citizenship question and that the court would allow the question for the 2020 census.

However, in May, new evidence came to light that that the citizenship question was adopted for reasons other than enforcing the Voting Rights Act.

Emails show that, for months, Ross had inquired about adding a citizenship question, asking around to see if it was a popular idea. Commerce Department officials had tried to get other agencies involved to “clear certain legal thresholds" to ask the question. As almost an afterthought, Ross and the Department of Commerce asked the Department of Justice to send them a letter providing the Voting Rights Act rationale for the citizenship question.

None of this evidence tends to support the conclusion that enforcing the Voting Rights Act was the true reason that the Department of Commerce sought to add a citizenship question to Census 2020.

The Supreme Court's legitimacy

As former New York Times Supreme Court reporter and Yale lecturer Linda Greenhouse has written, Roberts is concerned with the perceived legitimacy of the court.

Roberts has gone so far as to criticize Trump for criticizing an “Obama judge." In a November 2018 statement virtually unheard of from a chief justice, Roberts said “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges. ... What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them. That independent judiciary is something we should all be thankful for." The chief was defending the independence – and in effect the very legitimacy – of the federal courts, which he understood to be under attack by the president.

Given the weak justification for the citizenship question, rubber-stamping the citizenship question without further inquiry could well have been a stain on the court's legitimacy.

Just days before the Supreme Court handed down the decision in the census case, an appellate court had opened the door for further investigation into whether anti-Hispanic animus played a role in the secretary's decision to include the citizenship question.

This is a serious charge. To allow the citizenship question to be added to the census, in light of uninvestigated claims of anti-Hispanic animus and in the face of unquestionable anti-Hispanic impacts, could undermine the public trust in – and the very legitimacy of – the Supreme Court.

It has historically been challenging to facilitate immigrant participation in the census. In immigrant communities, fear of government has increased during the Trump administration. Indeed, just in the last few weeks, Trump threatened an imminent mass removal campaign, only to temporarily halt the effort at the eleventh hour.

The court might well have learned a lesson from its decision to uphold the travel ban last year, also on the last day of the term. In Trump v. Hawaii, a 5-4 majority in an opinion by Chief Justice Roberts overlooked the evidence of the Trump administration's anti-Muslim intent in adopting the ban and upheld it based on national security grounds. The decision was widely criticized by scholars and civil rights and immigrant advocates as authorizing discrimination.

Time will tell how the Trump administration proceeds from here. However, it would appear that a rational – not a “contrived" – explanation would be required.

The legal rationale

The court's decision, for the most part, does not state explicitly – which would be unprecedented – that it sought to protect its legitimacy. And it avoids going too far in criticizing the decision to use the citizenship question.

Indeed, the court found that the decision to include the question was not “arbitrary and capricious" in violation of the law. It simply said that the Department of Commerce's explanation was not convincing and a rational – not a “contrived" – explanation would be required.

It is telling that Roberts, who is keenly concerned about the court's legitimacy, sided with the liberal justices in order to send the case back to the agency.

Roberts, who famously said during his confirmation hearings that a judge's job is to call “balls and strikes,"resists the notion that the Supreme Court is a political institution – and did so, I believe, with this decision. ![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift