One of the most dangerous mistakes Americans are making right now is treating the threat to our democracy as a collection of daily outrages — the latest social media post, the latest threat, the latest norm broken. Those things are certainly bad, often stunningly so. But they are not the real problem. The real problem is structural, and it runs much deeper.

At his most charitable interpretation, Donald Trump does not think like an elected official operating inside a constitutional democracy. He thinks like a businessman. In that mindset, success is measured by dominance, efficiency, and loyalty. What produces results is kept; what resists is discarded. Rules are obstacles. Norms are optional. Institutions exist to serve the leader, not to restrain him. At present, this governing style is all about energizing perceived positives and minimizing perceived negatives. Increasingly, those “negatives” are people: immigrants, minorities, trans Americans, and the poor. The danger here is not just institutional; it is human. When checks and balances weaken, there are fewer brakes on policies that treat entire groups as costs to be managed rather than citizens to be protected.

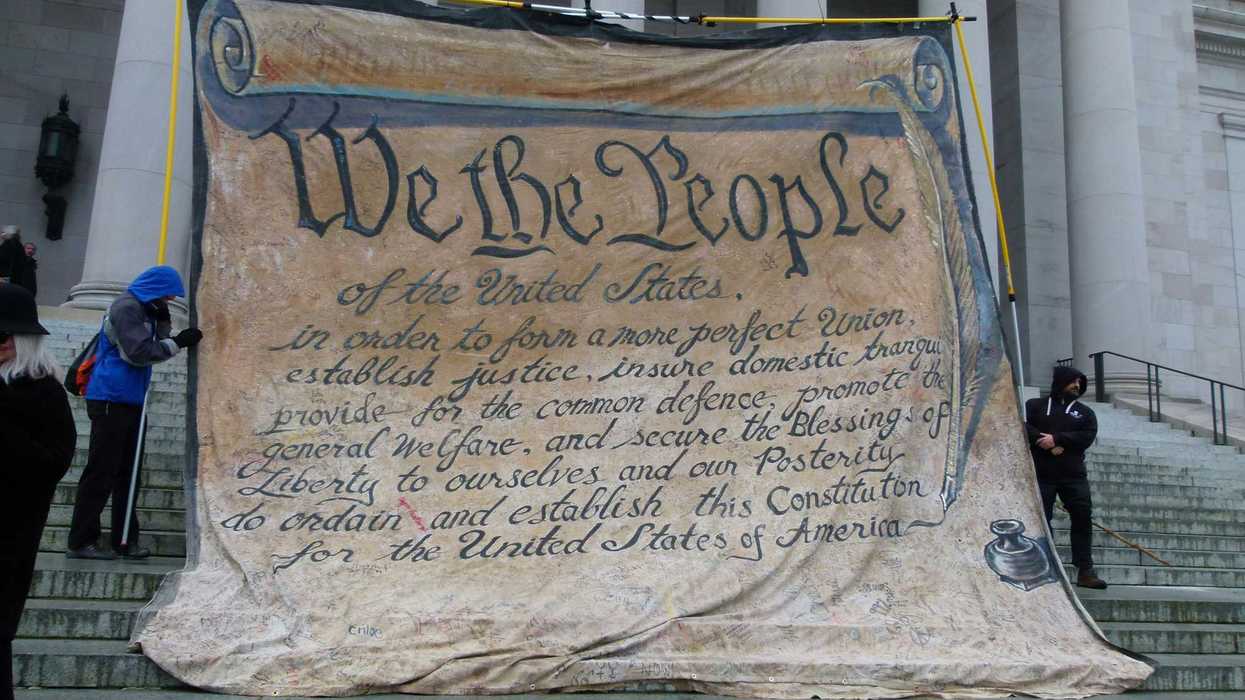

That worldview, by itself, should not be enough to upend American democracy. The Constitution was not designed to depend on presidential restraint. It was designed to counteract its absence. The Framers built a system with three strong, independent branches of government precisely because they assumed ambition, ego, and self-interest would always be present. One outlier, no matter how loud or aggressive, was not supposed to knock over every apple cart.

That safeguard is now failing.

The Constitution is explicit about the division of power between the federal government and the states. Election administration, for example, is assigned to the states under Article I, with Congress — not the president — permitted to alter those rules by law. The president has no constitutional role in this arrangement. This structure has been reaffirmed repeatedly by the courts. Federalism is not a custom or a courtesy; it is the architecture of the system.

That is why Trump’s recent suggestion that elections should be “nationalized” matters so much. It is not just unconstitutional; it reveals an assumption that Congress is a subordinate body rather than a coequal branch. If the most fundamental expression of democratic self-government — how we vote — can be spoken of as something the executive and his political party might simply take over, then the guardrails are already being treated as optional.

What has changed is not the Constitution. What has changed is the behavior of those entrusted to enforce it.

Today, the executive branch does not merely influence the legislative branch; it has effectively subsumed it. A majority of lawmakers in the president’s party have aligned their political survival with his approval. Through campaign fundraising ecosystems, endorsements, primary threats, media amplification, and the distribution of political favors, loyalty to the president is rewarded while independence is punished. Oversight is recast as disloyalty. Resistance is treated as betrayal. Power now flows in a closed loop: if you help keep the president in power, he helps keep you in power — and the legislative branch itself disappears inside that transaction.

In essence, Congress increasingly behaves like the junior partner — a little brother — rather than a coequal branch. Hearings vanish. Subpoenas go unused. The power of the purse is rarely asserted. Statements and proposals that would once have triggered immediate constitutional alarms are met instead with silence, deflection, or enthusiastic support.

This is how separation of powers collapses in civics textbooks. Even more alarmingly, it is also how it collapses in real life.

The judiciary has offered only partial resistance. While courts remain independent in principle, they are slow by design and cautious by temperament. Many judges, including a significant portion of the Supreme Court, were appointed by the same president now pushing the boundaries of constitutional authority. That does not mean judges act out of personal loyalty. It does mean that ideological alignment, procedural restraint, and institutional reluctance often blunt the courts’ willingness to confront executive overreach head-on, especially when Congress refuses to do its job first.

The Constitution was designed to withstand the ambition of individual actors within a branch; it was not designed for a moment when an entire coequal branch would so willingly bend the knee. In that vacuum, power need not be seized. It simply accumulates. Authority concentrates. Boundaries blur. The public is conditioned to see “the government” as a single entity with a single leader, rather than a system deliberately engineered to force friction, disagreement, and restraint.

If this sounds abstract, Americans need only look abroad to see how it plays out. Hungary used to be a constitutional democracy with courts, elections, and formal checks on power. Over the past decade, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has not abolished elections or openly dismantled democratic institutions. Instead, he fused executive and legislative power through party loyalty, weakened independent oversight, packed courts, and steadily reframed the state as an extension of his political movement. Elections continued. Courts remained open. But the system’s internal resistance eroded, and with it went meaningful democratic accountability. Hungary did not fall all at once. It slid.

Seen through this lens, the true danger is not any one proposal to “nationalize” elections, deploy federal agencies provocatively, or disregard precedent. Those are symptoms. The disease is the erosion of the democratic underpinnings themselves — the quiet abandonment of the idea that power must be contested in order to remain legitimate.

The Framers assumed ambition would counteract ambition. What they did not anticipate was a political culture in which party loyalty would eclipse national loyalty, and in which defending the Constitution would be treated as a political liability rather than a civic obligation. A constitutional system cannot survive on parchment alone. It requires people in power who are willing to say no and to stand up for America — even when it is inconvenient, risky, or personally costly.

That willingness is now in dangerously short supply.

If Americans focus only on the daily spectacle, they will miss the deeper story. The greatest damage being done is not the noise of any given day, but the normalization of a system in which one branch leads, another follows, and the third hesitates. That is not a temporary imbalance. It is a structural shift — and once those habits take root, they are extraordinarily difficult to undo.

The Constitution has not failed us yet. But it is being asked to function without the human backstop it depends on. That, more than any headline, is the real crisis we should be talking about.

Brent McKenzie is a writer and educator based in the United States. He is the creator of Idiots & Charlatans, a watchdog-style website focused on democratic values and climate change. He previously taught in Brussels and has spent the majority of his professional career in educational publishing.

Will Trump’s moves ever awaken conservatives?