Sometime in the next few days, 45-year-old Milton Thomas of Nashville is going to pick up his mail and find something that symbolizes another step in his ongoing journey toward being a productive citizen.

It's his voter registration card.

Thomas lost his right to vote when he was convicted of a drug-related felony – one of an estimated 6 million people nationwide disenfranchised because of felony convictions.

His return to the voting rolls is just one example of a slowly expanding nationwide movement to restore voting rights for convicted felons – one that has sometimes sparked controversy and also made for unusual political alliances.

Among the recent developments:

- Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis last week signed legislation requiring felons to first pay all fines and fees before having their voting rights restored – throwing up a major roadblock to many of the nearly 1.7 million Floridians who lost the right vote when convicted of a felony. That is the most of any state, according to 2016 estimates by The Sentencing Project.

- On Monday, 77,000 Nevadans had their voting rights restored when a new law went into effect allowing people on probation, parole or just having completed their sentences to vote.

- In Colorado, a similar law also took effect on Monday, allowing more than 11,000 convicted felons on parole to vote. Previously, parolees had to complete their sentences before having their voting rights restored.

- Members of the city council in Washington, D.C., last month introduced legislation that would allow convicted felons to vote while still in prison. Only Maine and Vermont allow convicted felons to vote while incarcerated.

These are just the latest examples of a trend – stretching back to the late 1990s – that has seen more than two dozen states modify felony disenfranchisement provisions to expand voter eligibility, according to The Sentencing Project.

Tennessee system is the most complex

Tennessee is not one of those states. In fact, according the Campaign Legal Center, it has the most byzantine system in the country for felons seeking to regain their voting rights.

And at more than 420,000, it trails only Florida, Texas and Virginia in the number of disenfranchised voters, and is second only to Florida when taken as a percentage of the voting age population. Further, it is near the top with an estimated 174,000 black disenfranchised voters, who comprise more than one-fifth of the black voting age population.

In response to the numbers and complexity in Tennessee, the CLC has hired three organizers for a nearly three-month program this summer. In addition to helping hundreds of Tennesseeans work through the process of getting their voting rights restored, the organizers also are trying to raise awareness about the process and identify and solve minor obstacles.

The effort is part of the CLC's Restore Your Vote campaign, which includes an online toolkit allowing people to click through a series of prompts to find out what they need to do to restore their rights or to help someone else.

Strange bedfellows, sometimes divisive

Restoring voting rights for convicted felons has sometimes brought together liberals and conservatives and also created divisions within the parties.

In Florida, with 1.7 million disenfranchised voters, an amendment to restore rights for those who have completed their sentences won by a large margin last fall – with the support of the Christian Coalition and with Republican operative Neil Volz leading the way for the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, the main group advocating for its passage. The Christian Coalition's support was based on "the biblical principles of forgiveness and redemption," according to its website.

But Republicans in the Florida legislature believed that felons should have to pay all their fines and fees before getting to vote.

The day DeSantis signed the bill, several civil and voting rights groups filed suit in federal court trying to block its implementation. In addition, the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition announced an initiative this week to raise $3 million to help convicted felons pay off outstanding fees and fines.

Among Democratic presidential candidates, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders supports allowing convicted felons to vote while still in prison – even those who have committed violet crimes. "The right to vote is inherent to our democracy – yes, even for terrible people," Sanders said.

Other Democratic candidates draw the line at not allowing prisoners convicted of violent felonies to vote, while South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg opposes allowing anyone still imprisoned for a felony to vote.

It's a long, winding road in Tennessee

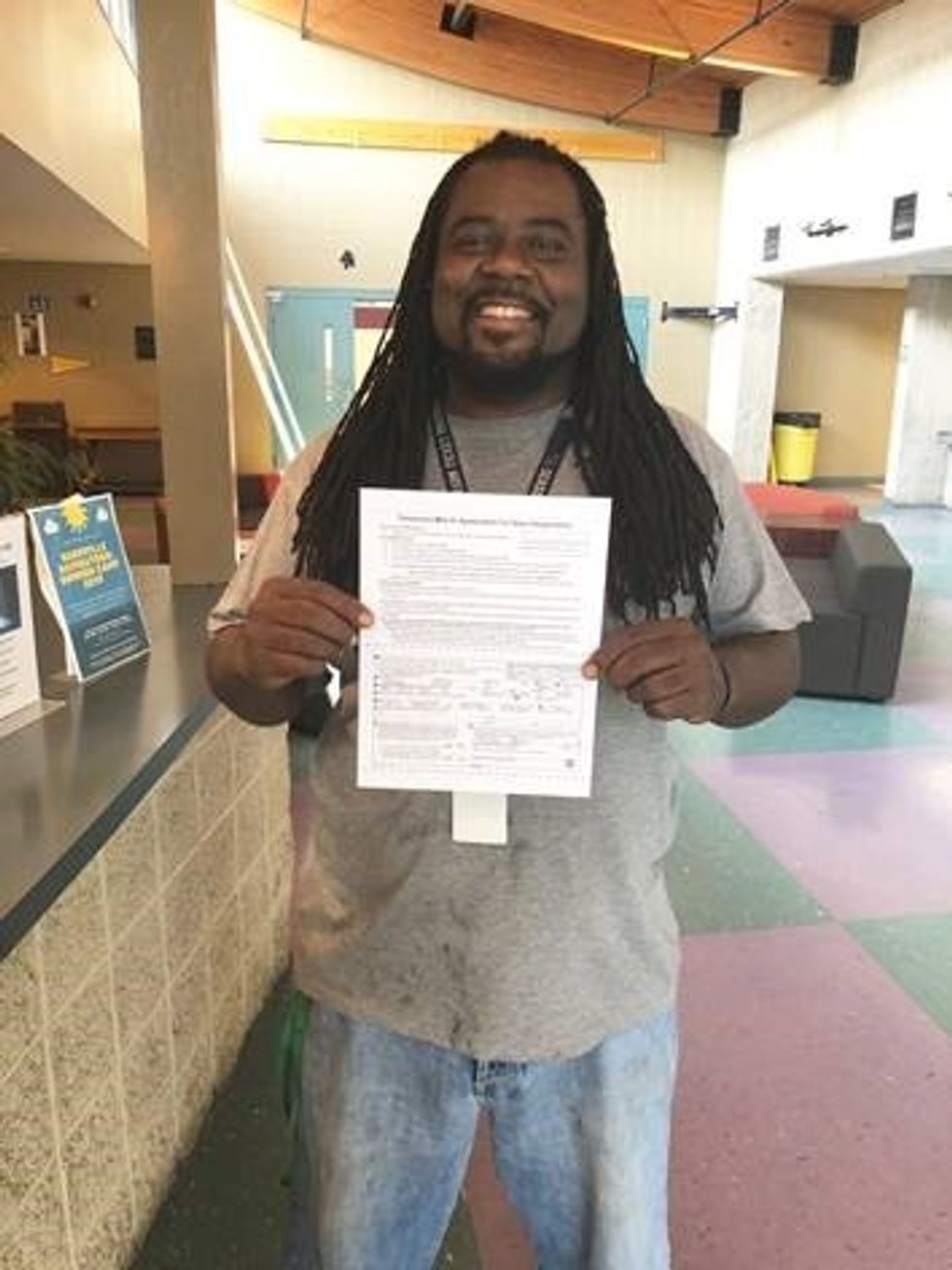

Milton Thomas of Nashville shows off his application to restore his voting rights. He expects to receive his new voting card soon. Restore Your Vote Tennessee

Milton Thomas of Nashville shows off his application to restore his voting rights. He expects to receive his new voting card soon. Restore Your Vote Tennessee

Campaign Legal Center staffers have created a map of sorts to show the various steps convicted felons in Tennessee must navigate to get back the vote.

There are so many permutations, depending on the type of crime committed and when it was committed, that it took someone like Gicola Lane to help Milton Thomas through it.

"I don't know a black family in Nashville not affected by incarceration," said Lane, a longtime Nashville community activist and one of CLC's three in-state hires. She said her first efforts to restore voting rights involved calling cousins and uncles.

For Thomas, next year's presidential election will be his first since casting a ballot for Bill Clinton. So far, he's not yet chosen a favorite.

"Early on they all promise you anything," he said with a chuckle.

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift