Marty Wulfe opened his inbox one day this fall and found an unsettling email from an old friend.

It was a dire warning from the Maryland chapter of Common Cause: Special interests in his state are pushing a "dangerous" proposal for a second constitutional convention.

But Wulfe himself was one of those special interests, because he's a board member of Get Money Out – Maryland. The organization is lobbying the General Assembly to have the state join five others calling for a convention to consider changing the Constitution to allow Congress and state legislatures to rein in money in politics.

While he and other Get Money Out leaders "had a good laugh at being labeled a special interest group," said Wulfe (who views himself as a big fan of Common Cause), the opposition from one of the most venerable voices for democracy reform is no laughing matter. Instead, the rift highlights one of the most impassioned arguments these days in the world of good-government advocacy.

At issue is the best strategy for slowing the flow of cash that's surged through the political system in the decade since the Supreme Court decided that limiting election spending by corporations, unions and advocacy groups violates the First Amendment.

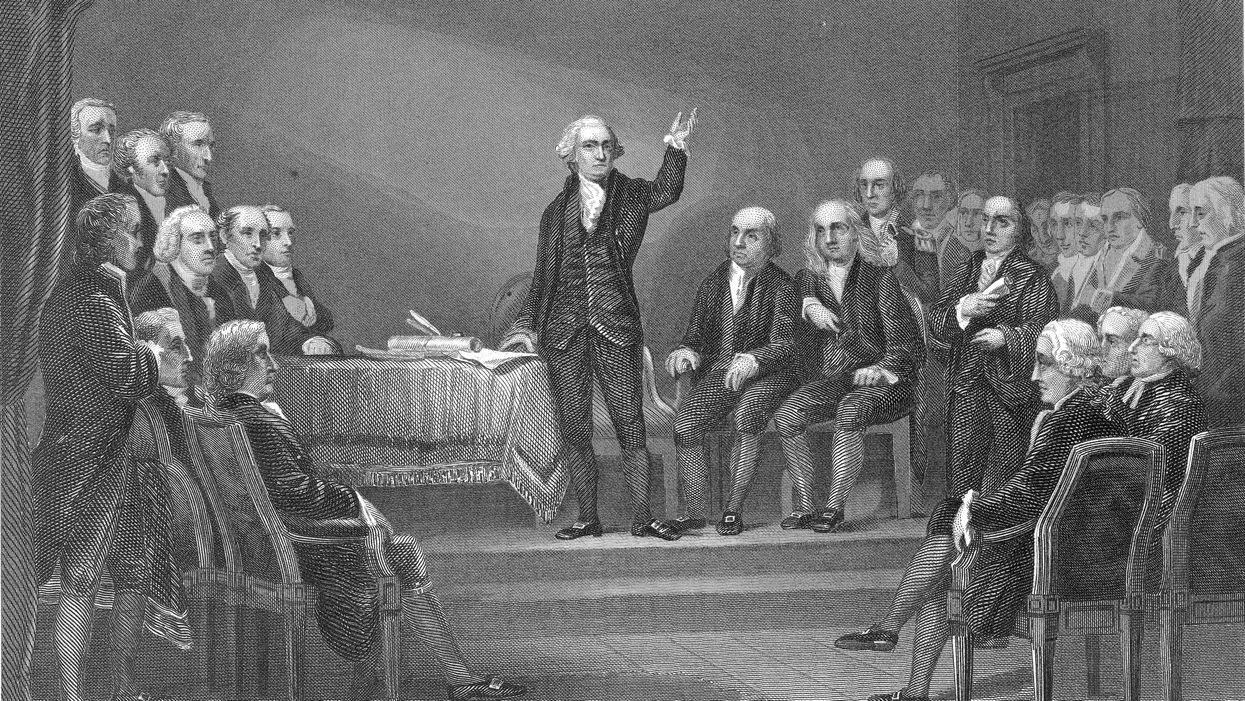

The underdog faction says calling the first constitutional convention since 1787, where the high court's landmark ruling in Citizens United vs. FEC could face a significant step toward effective reversal, is the cleanest and quickest solution. The more dominant faction favors the traditional but politically difficult method for altering the Constitution — supermajorities of Congress sending language to the states for ratification — fearing a convention would open a Pandora's box that conservatives could use to advance proposals that progressives would find horrific.

Wulfe, a retired researcher from the D.C. suburb of Silver Spring, said his group has struggled for years to convince the Democrats who control Annapolis to pass a resolution calling for a convention — in large part due to Common Cause's influence on progressive lawmakers. "I think that if Common Cause were to simply stop doing this, maybe not even change their minds, but just stop attacking us, we'd get this passed."

Common Cause sounds unlikely to drop its opposition to a convention. "There's a real concern about the process and what could come out of a convention," spokesman Jay Riestenberg said. "We see what some of these groups, particularly on the right, are trying to do to roll back reforms and progress we've made over the last century. That's why we think it's so dangerous."

Wulfe's group is part of a small coalition pushing the convention approach, including allied statewide organizations in Wyoming, New Mexico and Massachusetts. By far the most prominent national player on their side of the disagreement is Wolf-PAC, which takes credit for successfully convincing five state legislatures to call for a convention specifically to address campaign finance laws.

The fear of a so-called runaway convention, stoked by Common Cause and other left-leaning groups, has hampered Wolf-PAC's efforts in other states, said John Shen, the group's national legislative director.

"It definitely has caused quite a bit of damage within, at the very least, our movement," he said. "I think we can overcome it, but it would take substantially less time if more organizations joined us in advocacy."

Prominent allies of Common Cause in this debate include the Brennan Center for Justice, the Campaign Legal Center, Democracy 21 and more than 70 other national organizations. Last year, they signed a letter addressed to state legislators nationwide calling on them to oppose any and all convention resolutions.

But no group is as vocally opposed as Common Cause, which has been among the most influential good-government advocacy groups since its founding half a century ago and was a major force behind the last federal law to regulate campaign finance, in 2002. Its frequent emails to supporters about the dangers of a convention often include fundraising appeals — something that bothers those working to get a convention.

"It definitely leaves a bad taste in my mouth," Shen said. "That being said, my goal is not necessarily to defeat them — we will if we have to — but we would just love them to either stop fighting us or come around to being on the right side of the fight."

It works two ways

Under Article 5 of the Constitution, Congress must call a constitutional convention if it receives applications from 34 states and the applications all address the same topic. Whatever proposed amendment comes out of a convention would require the approval of three-quarters of the states, or 38 of them, the same as if the amendment were proposed by Congress. With such a high threshold, only proposals with broad and bipartisan support have a realistic shot at getting added to the Constitution in a national political environment that's close to evenly split ideologically.

Not enough support has coalesced around one issue to call a convention but states have endorsed (and rescinded) a handful of resolutions, and at the Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives is counting them.

Twenty-eight states want a convention to consider an amendment requiring the federal budget be balanced in almost all circumstances, an idea that fiscal conservatives have been pushing since the 1980s. Another conservative-led petition embraced by 15 states has a multifaceted goal. It seeks to "limit the power and jurisdiction of the federal government, impose fiscal restraints, and place term limits on federal officials."

Legal experts disagree on whether, once a convention is called, issues other than its original purpose can be considered. Wolf-PAC has produced a white paper saying the convention's agenda could be limited to a single topic. Common Cause has produced its own white paper drawing the opposite conclusion.

"We don't believe this kind of radical plan that is completely untested, and no one knows how it would work, is the right way of going about fixing that," said Common Cause's Riestenberg.

Not all the groups pushing to revive tighter regulation of campaign finance are committed to one of the two camps. American Promise, which has gained prominence with its campaign for what it assumes would be a 28th Amendment to limit money in politics, is among several that support the use of whatever mechanism works fastest.

"We don't know the pathway that's going to work in the end, but we know the danger if we don't fix this problem," said the group's president, Jeff Clements, who is confident the requirement of three-quarters of the states for ratification is a guardrail against radical plans getting added to the Constitution.

"Do I lose sleep about a convention? No, I don't lose sleep."