I’m in an unusual and uncommon line of work: I work on reducing toxic political polarization with the nonpartisan organization, Builders. As part of this work, I get to talk with Americans who may very much disagree politically but can agree it’s vitally important we detoxify our politics.

After the election, I’ve been listening carefully to the people in our community. I’ve listened to Democratic voters distraught at Trump’s election, who can’t understand how so many people could vote for someone like him.

I’ve listened to Trump supporters who are angered by the contempt they see aimed their way from the left — and perplexed by the left’s narratives and fears.

I’ve listened to independent and “politically homeless” voters who are frustrated by both “sides.”

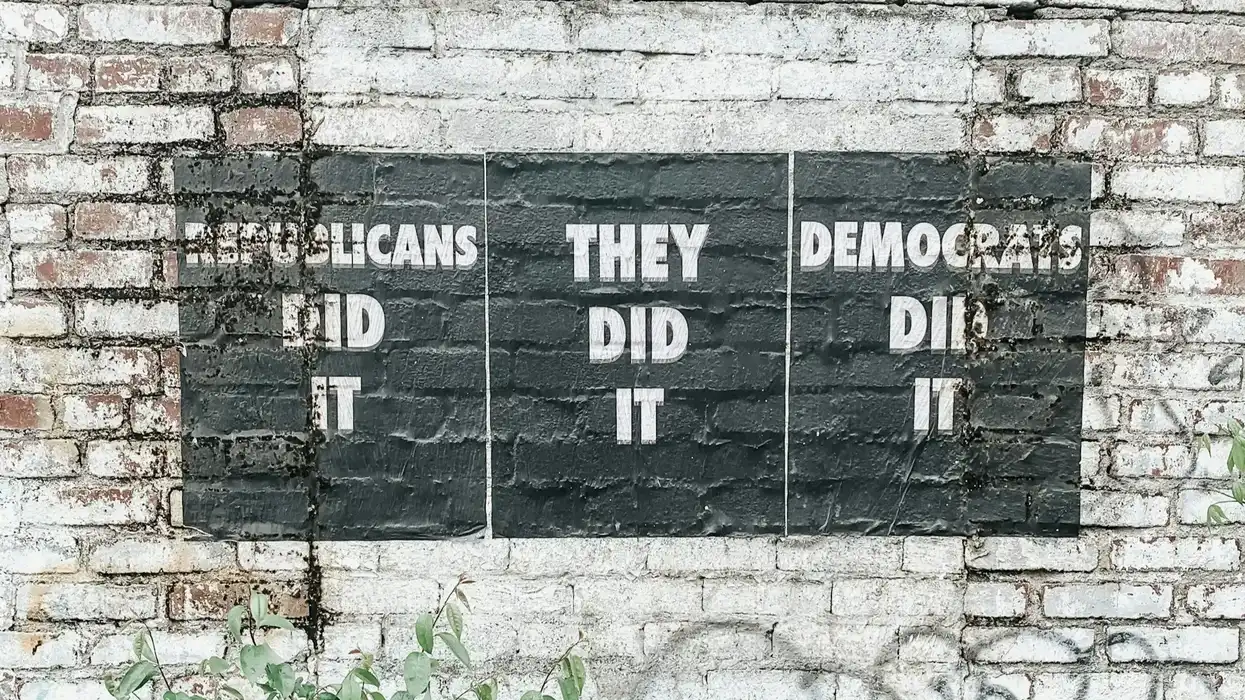

As I've listened, one idea has increasingly stood out to me as very important and yet under-examined: Republicans and Democrats are not symmetrical groups. They are not like two sides of a chess board, with the same pieces. They have very different traits. They move in different ways.

And yet, we often try to compare them as if they were similar — as if they were mirror-images of each other. We look for the bad things our opponents do and, because we don’t find equivalent versions of those things on “our side,” we think “this toxicity is all their fault.”

Meanwhile, our opponents will do the same thing: they’ll get angry about bad and extreme things they see on “our side” that they don’t see on “their side.”

For example, one oft-heard argument on the left for why our divides are Republicans’ fault is: “There’s no Democratic Party version of Trump.” They mean: There’s no major Democratic leader who speaks in an aggressive and divisive way as Trump; no one who has promoted distrust of election results like Trump has done (to name a few things).

Because they see no equivalent on the left for these things they see as extreme and dangerous, that leads them to think, “Our toxic divides are the fault of Trump and the Republicans.”

It may be true there is no “Democratic version of Trump,” but there are other, different Democratic things that serve as sources of Republican anger. For example, there are the big swings in Democratic stances in recent years (as Republican stances largely stayed the same).

This difference leads many to conclude it’s the Democrats who have become extreme and unreasonable. Because there’s no mirror-image equivalent of those stance shifts on the right, it can be easy to conclude, “Our toxic divides are the left’s fault.”

Those are just a couple examples, but there are many areas of asymmetry. There are asymmetries in education, in religion, in how the parties think and strategize, and more.

One major area of asymmetry is that liberals dominate major cultural institutions, like academia, news media, and entertainment media. This asymmetry can help explain Republicans feeling misunderstood and frustrated (and maybe helps explain early support for Trump’s aggressive style).

For some Republicans, Trump’s aggressive style is an understandable response to the aggressions and toxicity they perceive on the left. As is standard in conflict, people focus on the threats from the “other side” — meaning any negative things on one’s own side are easily overlooked.

Republicans I’ve talked to emphasize the toxicity they’ve seen and faced from liberals. It’s true there are many pieces of evidence for it. For example, Democrats are more likely to cut off friendships for political reasons. This can be used as another building block for the “this is Democrats’ fault” narrative.

But, on the other hand, one could make the case that this group difference is largely due to Trump’s divisive personality. One could imagine a Democratic version of Trump causing Republicans to be the ones cutting off more friendships.

We have to face the fact that it’s simply easy for us to form defensible narratives of how it’s the “other side” that has gone crazy and is the unreasonable aggressor. And once we’re “in” one dominant narrative or the other, it can be hard to see all the various building blocks our adversaries have used to form their narratives.

We’ll always find it hard to see how anyone can see us as the bad guys.

This dynamic leads us to essentially gaslight each other. We speak as if the “other side” is crazy and irrational. We interpret everything they say in maximally pessimistic ways. Our public discourse becomes a toxic stew of insults and threats, real and perceived: a place where anyone can easily build all sorts of dark narratives about the moral badness of any group.

To be clear: I’m not arguing that anyone should or must think both groups are equally at fault for our toxic divides. But one can think “the other side is more at fault” while seeing that our conflict is complex and there are ways that both sides contribute.

This helps us see that when we frame our divides in simplistic “it’s all their fault” ways, we ourselves will contribute to the toxicity of the conflict.

As I’ve listened to many Americans talk about their fears and anger, it has emphasized to me that understanding each other is more important than ever. I know that sounds like a kumbaya cliche, but I (and many others) believe it’s true.

We need more people to really try to see what the “other side” sees: to be willing to see how rational and compassionate people can see a person's group as the "bad guys."

The truth is that we’ve scarcely tried to understand each other as a nation. We’ve been caught in a decades-long cycle of increasing rage and contempt. And, if we want to get out of it (which we know most Americans do), we’ll need a lot more people to approach our divides with humility and empathy.

To Overcome Our Divides, We Must Try to Understand the Other Side’s Ange r was first published by Independent Voter News, and was republished with permission.

Zachary Elwood works with Builders, a nonpartisan organization equipping people to overcome toxic polarization and solve our toughest problems. He’s the author of “ Defusing American Anger. ”

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift