The death of Rev.Jesse Jackson is more than the passing of a civil rights leader; it is the closing of a chapter in America’s long, unfinished struggle for justice. For more than six decades, he was a towering figure in the struggle for racial equality, economic justice, and global human rights. His voice—firm, resonant, and morally urgent—became synonymous with the ongoing fight for dignity for marginalized people worldwide.

"Our father was a servant leader — not only to our family, but to the oppressed, the voiceless, and the overlooked around the world,” the Jackson family said in a statement.

Jackson Sr. died on Tuesday at the age of 84. His family announced that he passed peacefully, surrounded by loved ones, after years of declining health linked to progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), a degenerative neurological disorder he had lived with for more than a decade. Jackson had also publicly disclosed a Parkinson’s diagnosis in 2017.

Born in Greenville, South Carolina, Jackson came of age in the segregated South, where he quickly developed a passion for activism. He attended North Carolina A&T State University, earning a degree in sociology before pursuing divinity studies at the Chicago Theological Seminary. It was during this period that he became deeply involved in the civil rights movement, joining demonstrations and organizing student support for the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Jackson participated in the historic 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery march and soon joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), working closely with King. He rose rapidly within the organization, eventually leading Operation Breadbasket, the SCLC’s economic empowerment initiative. King praised Jackson’s leadership, noting that he had “done better than a good job” in advancing the program’s mission.

Jackson was present at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis when King was assassinated in 1968—an event that profoundly shaped the rest of his life’s work.

“He taught me that protest must have purpose, that faith must have feet, and that justice is not seasonal, it is daily work,” fellow civil rights activist the Rev. Al Sharpton wrote in a statement.

What made Jackson different from many of his contemporaries was his instinct for building coalitions. He understood that the fight for civil rights could not be waged solely within the Black community. His founding of People United to Save Humanity (PUSH), later known as the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, in 1971was an attempt—radical for its time—to unite the poor, the marginalized, and the politically alienated across racial and ethnic lines.

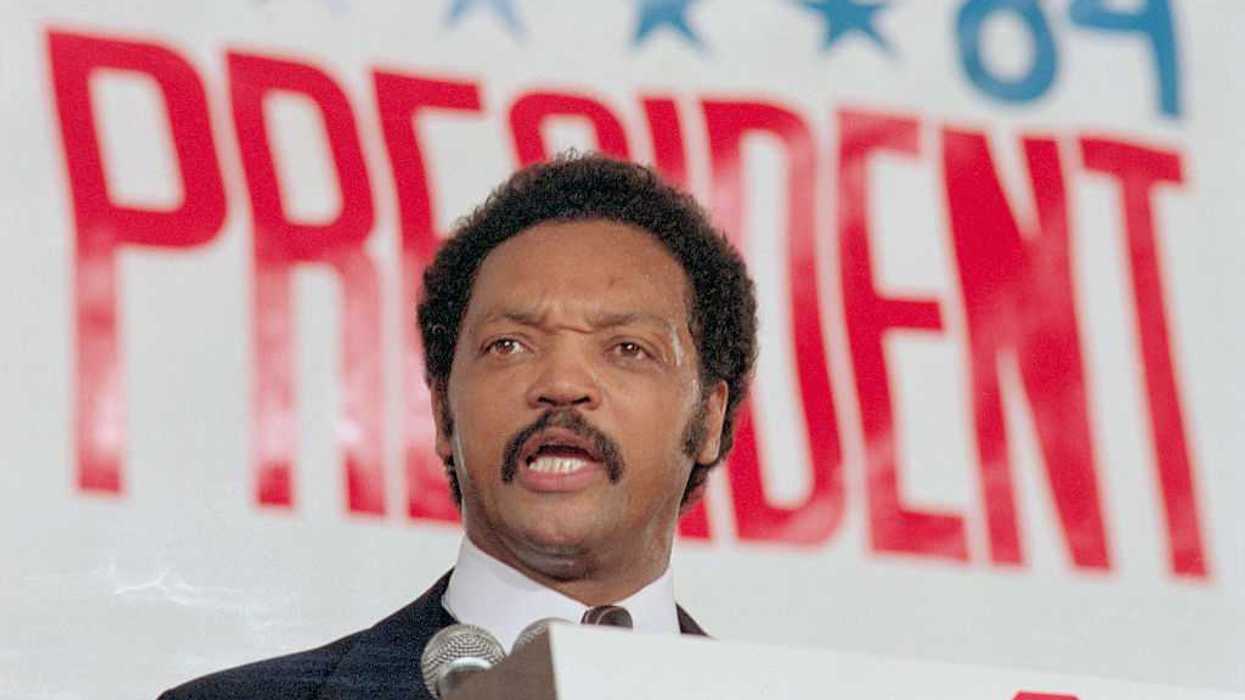

Jackson’s political influence grew further when he launched two groundbreaking presidential campaigns. In 1984, he became the second Black American to mount a national presidential bid, winning more than 18% of the primary vote. Four years later, he expanded his coalition, winning 11 primaries and caucuses and demonstrating the electoral potential of a multiracial, progressive movement.

His campaigns helped reshape the Democratic Party, pushing issues of poverty, racial justice, and foreign policy into the national spotlight. Jackson proved that a multiracial, progressive coalition was not only possible but powerful.

Rev. Jackson secured the release of Americans detained abroad, including U.S. soldiers held in Yugoslavia in 1999, a U.S. Navy pilot captured in Syria in 1984, and hundreds of women and children trapped in Iraq in 1990. President Bill Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2000 for these efforts.

His humanitarian work reinforced his reputation as a global advocate for peace and justice.

In his later years, Jackson remained outspoken on issues ranging from voting rights to economic inequality. He criticized political leaders across the spectrum and continued to champion progressive causes, endorsing Sen. Bernie Sanders during the 2020 presidential campaign.

His health began to decline significantly in the 2010s and 2020s. PSP limited his mobility and speech, and he spent periods hospitalized before transitioning to outpatient care in Chicago. Despite these challenges, he continued to make public appearances and remained engaged with Rainbow PUSH initiatives.

"His longevity is part of the story," said Rashad Robinson, the former president of the seven-million-member online justice organization Color of Change. "This is someone who had so many chances to do something else. And this is what chose to do with his life."

Rev. Jackson's critics often accused him of being too ambitious, too outspoken, too willing to insert himself into the spotlight. But ambition is not a sin in the fight for justice. Outspokenness is not a flaw when silence is complicity. And visibility is not vanity when the issues at stake are life and death for millions.

Jackson’s life was defined by a simple but profound conviction: that America could and must be better. His voice may be gone, but the movement he helped build continues to echo through the ongoing struggle for equality.

Hugo Balta is the executive editor of The Fulcrum and the publisher of the Latino News Network.

U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth speaks during a news conference at the Pentagon on March 2, 2026 in Arlington, Virginia. Secretary Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dan Caine held the news conference to give an update on Operation Epic Fury. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images) (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth speaks during a news conference at the Pentagon on March 2, 2026 in Arlington, Virginia. Secretary Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dan Caine held the news conference to give an update on Operation Epic Fury. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images) (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Trump needs to get ready for the blowback