Pearl, the author of “ ChatGPT, MD,” teaches at both the Stanford University School of Medicine and the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He is a former CEO of The Permanente Medical Group.

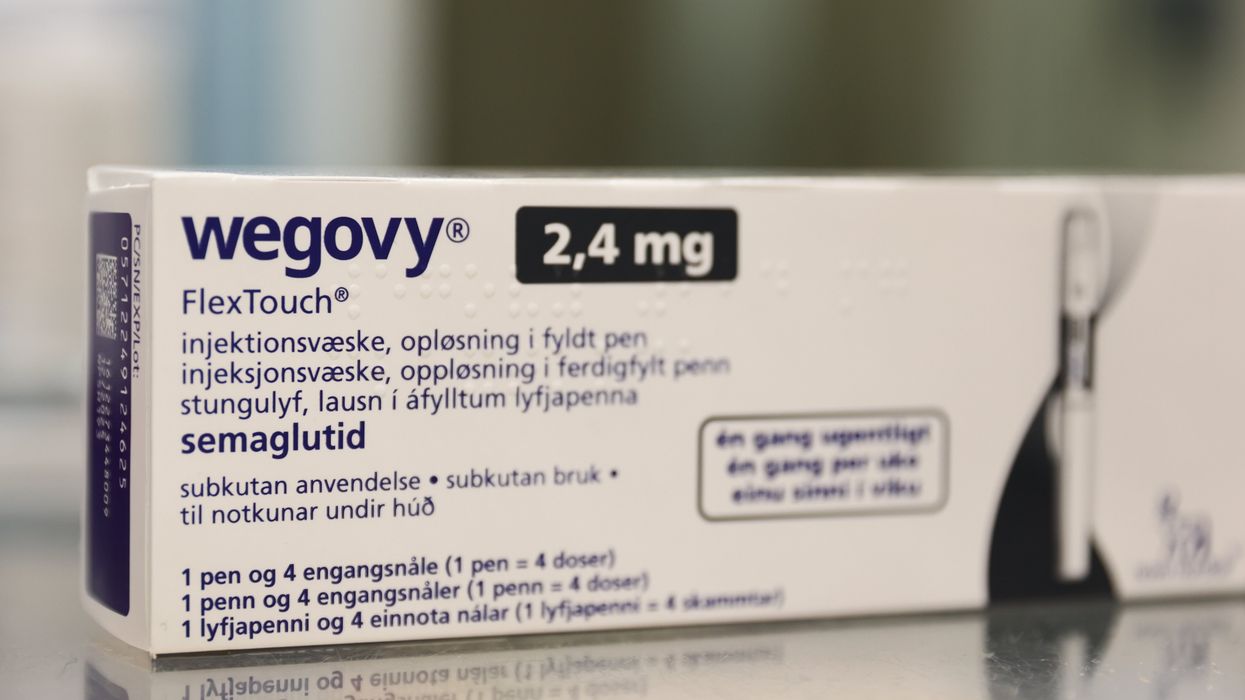

A whopping one in eight U.S. adults have taken GLP-1 drugs like Wegovy and Ozempic for weight loss and related conditions. Their popularity and efficacy have sparked a prescription-writing frenzy in recent years, leaving both medications on the Food and Drug Administration's drug shortage list since May 2023.

But even when the supply rebounds, access to these drugs will remain out of reach for the majority of Americans. That’s because brand-name versions of the drugs range from $11,000 to $16,000 a year, prices that are unaffordable for most people.

Attempts to control prices through legislation face significant hurdles, both in the divided halls of Congress and in the courts, where determined legal challengers await. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, hopes that applying pressure at upcoming hearings will force Novo Nordisk, maker of Wegovy and Ozempic, to lower prices voluntarily. History shows that pharmaceutical companies rarely bend on prices, even in the face of public scrutiny.

Fortunately, Congress can implement a straightforward solution to make these drugs affordable, thereby improving the nation’s financial and physical health. Before explaining that strategy, here’s why our nation needs effective, affordable and available weight-loss medication.

Framing the obesity epidemic

Around 42 percent of American adults are obese, putting them at dramatically elevated risk for a host of complications: diabetes, heart disease, kidney failure, leg amputation, cancer and severe musculoskeletal problems. The economic impact of obesity is staggering, with related health care costs estimated to be $260 billion annually.

For decades, health experts have pleaded with Americans to exercise more, eat better, and make lifestyle improvements while urging lawmakers to regulate food and address the “social determinants of health” that lead to excess weight gain. Currently, billions of taxpayer dollars are spent on government-run nutrition and exercise campaigns — on top of the $190 billion Americans spend on weight loss products, programs and supplements.

Despite these extensive efforts and expenditures, obesity rates continue to climb, as do the associated consequences, contributing to as many as 500,000 preventable deaths every year.

The outsized promise of GLP-1 drugs

Studies show that all GLP-1 drugs lead to major weight loss, averaging 15 percent of a user’s body mass. And when obese individuals combine regular exercise with semaglutide, the active ingredient in Wegovy, they shed an average of 34 pounds.

Beyond weight loss, GLP-1 medications have been shown to reduce the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular events, prevent kidney failure and potentially improve cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer’s.

Despite all the known and potential benefits, the high price of weight-loss medications forces insurers and employer health plans to limit coverage, leaving many patients without access to these beneficial solutions.

The current financial burden

The cost of providing 100 percent of obese Americans with GLP-1 medications would surpass $1 trillion a year, even with drug rebates. For perspective, that’s more than twice what Americans spend on all prescription drugs annually. Moreover, that figure dwarfs the $260 billion in projected savings if obesity were eradicated.

And because patients who stop taking the medication regain an average of two-thirds of the weight they’ve lost, that trillion-dollar annual cost would persist indefinitely. From the vantage of the U.S. health care system, this ongoing expense (an estimated 25 percent annual bump in total health care spending) would strain funding for other vital components of care, including hospitals and clinicians. It would also drive insurance premiums and out-of-pocket costs through the roof.

A recent report from Sanders’ office highlighted the stark disparity in global pricing for GLP-1 medications: Americans pay over $1,300 for a 28-day supply of Wegovy while patients pay far less in countries like Denmark ($186), Germany ($137) and the United Kingdom ($92).

This is because nearly all national governments, except for the United States, negotiate the price of prescription medications, rather than allowing drug companies to charge whatever they deem best for their shareholders.

The hidden truth

Contrary to what people might assume, these drugs are not expensive to make. A team of Yale and Harvard scientists determined that semaglutide can be manufactured for less than $5 per month.

In May 2024, telehealth company Hims & Hers began selling a compounded (pharmacist created) version of the GLP-1 drug semaglutide for $199 per month, about 85 percent less than the brand names Wegovy and Ozempic. This reflects a profitable, but more appropriate, price point.

Hims & Hers can sell its version of these patented weight-loss drugs because Congress has authorized the compounding and sale of a patented drug when there is an FDA-determined drug shortage. However, once the GLP-1 shortage is resolved, companies like Hims & Hers will be required to cease production. This will compromise the health of current users and price out many more Americans still struggling to lose weight.

A creative solution for the FDA and Congress

Congress can make these lifesaving weight loss medications affordable for all eligible Americans by expanding the FDA’s definition of “drug shortage.” Whereas “shortage” currently refers only to inadequate supply, a more modern definition would include medications that are unaffordable and therefore inaccessible to millions of people.

By amending the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, this expanded definition would allow compounded versions to remain available at a reasonable price, even when weight-loss drug manufacturers increase production.

The reason drug manufacturers price GLP-1s at $10,000 to $16,000 a year has little to do with research and development, overhead, or manufacturing costs. The reason is simple: greed.

Such pricing strategies might be tolerable in other industries, but when the health of tens of millions of Americans is at risk, Congress has an obligation to act. Expanding the definition of “shortage” would break the monopolistic hold of current manufacturers, improve public health, save lives and incentivize GLP-1 manufacturers to reduce prices. The time for legislative action is now.

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room