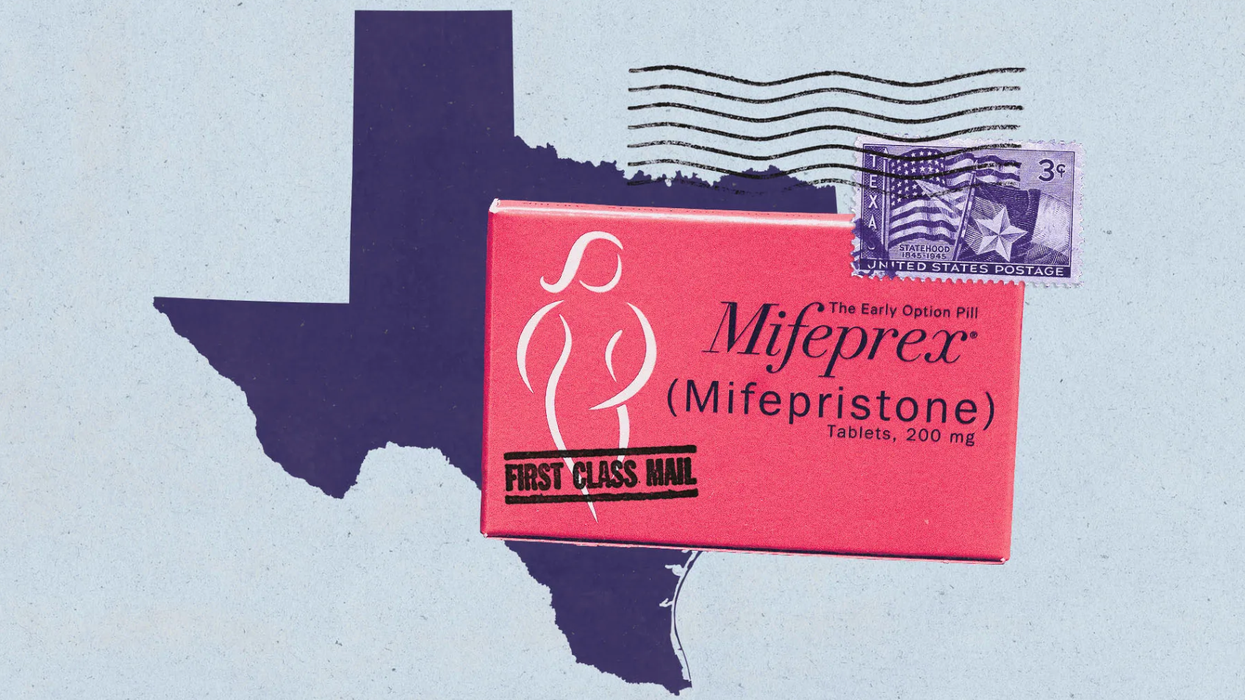

Texas’ massive new abortion law taking effect this week could escalate the national fight over mailing abortion pills.

House Bill 7 represents abortion opponents’ most ambitious effort to halt telehealth abortions, which have helped patients get around strict bans in Texas and other states after Roe v. Wade was overturned. The law, which goes into effect December 4, creates civil penalties for health care providers who make abortion medications available in Texas, allowing any private citizen to sue medical providers for a minimum penalty of $100,000. The bill’s backers have said it would also allow suits against drug manufacturers. It would not enable suits against the people who get abortions.

Though other states have passed legislation targeting abortion medications — classifying them as a controlled substance, for instance — the Texas law is novel in its approach to targeting the people who distribute them and its reliance on civil suits.

Medical providers say the law won’t stop them from providing abortions to people in Texas. Three major telehealth practices confirmed that they intend to keep prescribing and mailing abortion medications to patients in Texas, citing other states’ laws that would shield them from Texas-based suits. Elisa Wells, the access director of Plan C, which lists abortion options for people across the country, said she has not heard from any providers about plans to stop offering telehealth abortions to Texans.

“If anything, the implementation of this law makes people more determined to help folks in Texas access abortion pills,” Wells said.

Pharmaceutical companies have not clarified how they will respond. Danco, one of the principal manufacturers of the abortion medication mifepristone, declined to comment. GenBioPro, which manufactures a generic version of the drug, also declined to comment.

However, anti-abortion activists who championed the law say they plan to launch civil lawsuits against health care providers who continue to mail medications to Texas. Those private suits could accelerate a clash between state abortion laws that is widely expected to be resolved by the conservative U.S. Supreme Court.

At issue is the conflict between individual state abortion restrictions and shield laws in other states that protect abortion providers from out-of-state prosecutions. Those laws say that state governments will not comply with extraterritorial efforts to punish health care providers for offering services legal in the state where they reside — including abortions. Almost half of all states have some form of shield law, though only eight explicitly protect providers no matter where a patient is located.

Under those laws, medical professionals living in states where abortion is legal have continued to mail medications patients can use to end their pregnancies from home — a method that is well-studied and effective with rare complications. Research suggests that 1 in 4 abortions are now done through telehealth, with about half of those in states with bans or restrictions.

The method’s popularity has made telehealth a top target for abortion opponents. No state has effectively halted the provision of telehealth abortions into states with bans, but HB 7’s implementation introduces a new tool for anti-abortion activists to leverage.

“We are building partnerships, we are educating our friends and other Texans about what the law is and what would be needed — and putting a team in place for if we actually need to bring one of these lawsuits at the end of the year,” said John Seago, head of the anti-abortion group Texas Right to Life, who played a leading role in shepherding HB 7.

That has involved meeting with abortion opponents across the state, including those who run anti-abortion centers, organizations that resemble medical clinics but instead deter people from terminating their pregnancies. Many also market services such as “post-abortion counseling.” Those offerings can put them in touch with people who have used telehealth for an abortion, and who could be sources for potential suits — especially given the dearth of dedicated reproductive health facilities in the state. Anti-abortion centers were a key source of support for HB 7.

“These contacts have the potential to come into contact with someone who had ordered these pills, or these pills were given to them, and they would have firsthand experience of how the pills got into Texas,” Seago said. “Those are the types of individuals we need to partner with to bring these lawsuits most effectively. We are definitely building that network out.”

Already, health professionals mailing abortion pills to Texans have been sued. The state Attorney General Ken Paxton has brought a case against Margaret Carpenter, a physician in New York, for mailing abortion pills to the state. (In New York, state officials have cited the shield law in declining to enforce a Texas court’s ruling that fined Carpenter $113,000.) Jonathan Mitchell, a prominent lawyer who has helped craft many of the state’s anti-abortion laws, has brought wrongful death lawsuits — typically used to sue someone for a death caused by negligence or recklessness — against multiple telehealth providers, arguing an abortion is the death of a person. Those cases are still making their way through court.

The new law could strengthen Texas’ case against telehealth. Mitchell has indicated in court documents that he intends to amend at least one civil case — a wrongful death brought against California-based Dr. Remy Coeytaux — after the law takes effect. He did not respond to a request for an interview.

Health care providers are watching that case closely, with some saying it could provide key insight into whether and how the new law could affect their risk.

“That will give us some information about what this is going to look like and how that moves through the courts,” said Dr. Angel Foster, who founded the Massachusetts Medication Abortion Project, a major telehealth practice. “And again, it’s going to be an opportunity for us to see shield laws in action.”

HB 7 closely resembles a 2021 Texas law that effectively outlawed abortions after six weeks of pregnancies — the majority of abortions — months before the fall of Roe v. Wade. That law pioneered the use of private civil suits to stop the provision of most abortions.

Though the law halted abortion providers from operating in the state, there were no successful lawsuits against health care providers. That reality, coupled with the rise of blue state laws to protect health care providers, has left many who offer telehealth skeptical that the new Texas law will immediately reach them.

“We are confident this is exactly what the Massachusetts shield law is meant to protect us from: civil penalties related to providing legally protected reproductive health care, which is what we’re doing,” Foster said. “I’m not naive that there could easily be suits, and that means our lawyers will have to be involved in handling that. There’s energy involved in ignoring something. But we’re not changing anything about our practice and not anticipating any changes to our practice in regard to HB 7.”

Texas’ New Abortion Ban Aims To Stop Doctors From Sending Abortion Pills to the State was originally published by The 19th and is republished with permission.