On January 22, the United States finalized its exit from the World Health Organization. This move did not come as a surprise. The process began more than a year earlier, the day after President Trump took his oath of office for a second term. His dislike for the world body and its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic is well known, as is his deal-making approach in foreign policy.

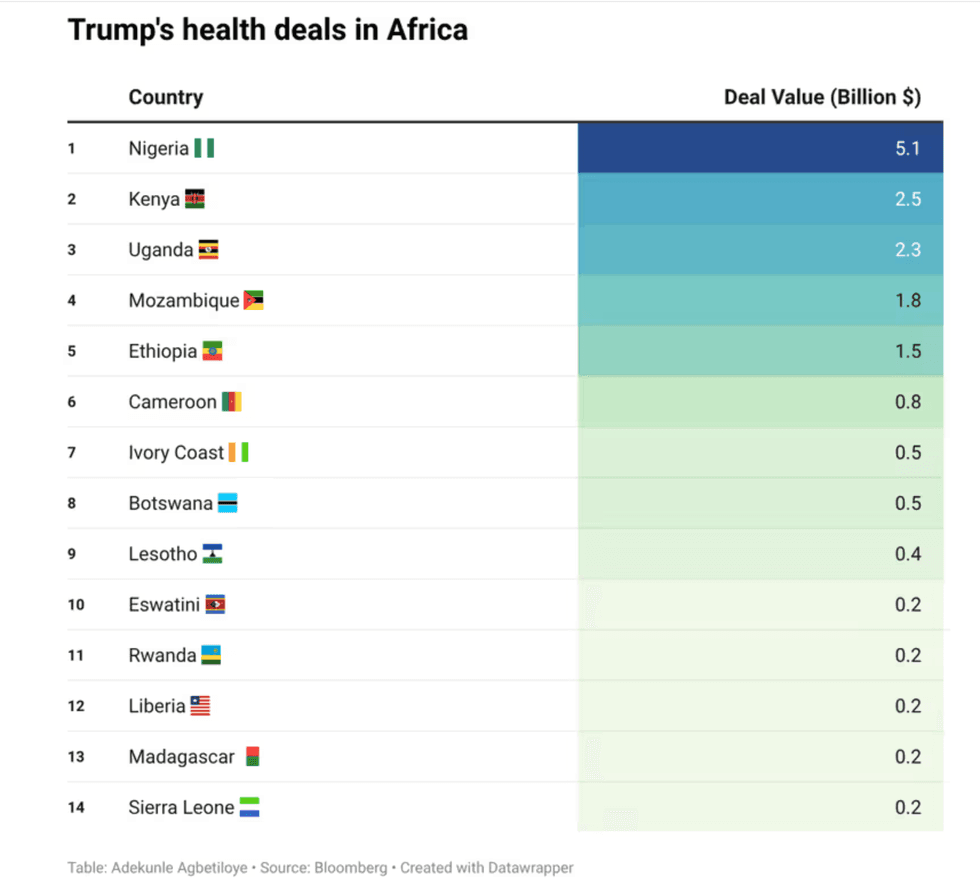

Trump’s logic is driven by self-interest and the notion of “What’s in it for us?” This transactional approach became even more apparent in December, when the U.S. Government signed 14 bilateral health agreements with African nations totaling US$ 16 billion.

The sum is significant, particularly given that all U.S. foreign assistance was abruptly halted in February 2025, when Elon Musk's Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) dismantled the Agency for International Development (USAID). The evisceration of USAID led to an estimated 600,000 deaths in 2025 alone and left many countries scrambling to fill gaps in their health sectors.

These multiyear bilateral agreements, known as health compacts, are central to the America First Global Health Strategy, released by the Trump Administration last September. Though not legally binding, the compacts are described as a “strategic mechanism” to advance “U.S. priorities, make America prosperous, and protect the U.S. economy from infectious disease outbreaks.”

Redefining the terms of engagement in global health is not inherently problematic. But making those terms explicitly transactional risks undermining global cooperation and weakening collective preparedness for future health crises. In an era of artificial intelligence and large language models trained on massive datasets, the bilateral health agreements raise concerns about health data privacy and the potentially extractive nature of arrangements that appear to favor U.S. companies.

“I am not opposed, by definition, to the idea of a compact,” a former USAID official told The Fulcrum, speaking on conditions of anonymity. “It’s true that African countries have not provided for enough of their own health care because they got a lot of support from the U.S. Negotiating with countries and defining their responsibilities as well as ours is not a bad idea. But provisions that give the U.S. access to their data in perpetuity are unacceptable.”

The obligation to share health data, research on pathogens, and even login credentials with the U.S. Government for a period longer than the bilateral agreement itself is indeed a sticking point. In Kenya—the first country to sign such an agreement—the High Court has suspended implementation of parts of the deal pending a hearing on data privacy.

- YouTube youtu.be

Watch a video on the signing of the first health agreement with Kenya, which highlights some of the issues raised re data privacy

Additional concerns include the lack of transparency around country selection and contractual terms—only the first one with Kenya was shared publicly—the co-financing requirement that may strain local health systems, and the significant power imbalance between the U.S. and countries agreeing to sign these deals in exchange for health aid.

Notably absent from the current rounds of agreements are South Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo. South Africa has been in the crosshairs of this Administration for its pro-Palestine stand with the International Criminal Court. In the DRC, health assistance may yet become leverage in negotiations over U.S. access to critical mineral reserves.

“Bilateral MOUs under the America First Global Health Strategy carry both opportunity and risk,” writes Ebere Okereke, an associate fellow with the global health program of Chatham House, London. “African governments should approach these agreements with discipline. National priorities must come first. Co-investment in national systems should be nonnegotiable. Data governance, reciprocity, and multiyear financing need to be explicit. Deals that shift cost without commensurate benefit should be resisted.”

René Lake, a Senegalese political analyst and journalist based in Washington, echoes that caution. “From an African perspective, this approach can offer greater clarity and speed of implementation,” he told The Fulcrum, “But it also raises questions about asymmetry, sustainability, and local ownership.” The central issue, he said, is whether these agreements enhance policy autonomy or reinforce dependency. “The real test will be how much space African governments retain to set their own health agendas.”

As for the U.S. withdrawal from the WHO, the former USAID official believes the move is ultimately temporary. Global coordination, he argues, is indispensable for managing health threats. Since germs don’t respect borders, going at it alone is shortsighted and ineffective at its best. But U.S withdrawal, and its refusal to even pay US$ 260 million, which it owes for 2024-2025, will have ripple effects globally.

Paradoxically, the spending bill recently passed by the Senate includes US$50 billion in foreign assistance and substantial funding for global health, nearly on par with pre-Trump levels. “The question,” the former official said, “is whether the administration feels obligated to spend it.” Traditionally, appropriations were treated as law. “This administration seems to view them as a suggestion.”

Even if some of that funding is released, how it would be channeled remains unclear. “They don’t like traditional implementers, and local capacity is limited,” he said. “They may want to give it to their friends, but they can’t move US$9.5 billion that way. Obligating that scale of funding directly to host governments through bilateral agreements and hoping for the best would be reckless.”

Beatrice Spadacini is a freelance journalist for the Fulcrum. Spadacini writes about social justice and public health.

Native American women face higher rates of death than other demographics. (Oona Zenda/KFF Health News)

Native American women face higher rates of death than other demographics. (Oona Zenda/KFF Health News)

Marco Rubio is the only adult left in the room