In a time of deep polarization and democratic fragility, bridgebuilding has become a go-to approach for fostering civic cohesion in the U.S. Yet questions persist: Does it work? And how do we know?

With declining trust, rising partisanship, and even political violence, many are asking what the role of dialogue might be in meeting democracy’s demands. The urgency is real—and so is the need for more strategic, evidence-based approaches.

Over the last decade, a growing number of organizations have launched bridgebuilding initiatives: efforts designed to reduce division through dialogue, relationship-building, and developing mutual understanding across lines of difference. Some well-known examples include Braver Angels, Millions of Conversations, and BridgeUSA.

Many bridgebuilding initiatives are rooted in contact theory—the idea that positive interaction between groups can reduce prejudice and improve intergroup attitudes. Contact is a powerful and important approach—yet a growing body of research suggests that focusing solely on attitudes may not be enough to drive real small-d democratic change. As a democracy strategist and a program evaluator, we’ve spent the past few months collaboratively consolidating our thinking on what makes bridgebuilding effective and how it can be strengthened.

Here’s what we’ve concluded: if bridgebuilding is to fulfill its highest potential in contributing to a just, cohesive society, we should focus on behavior change, understand the limits of contact theory, and hone our skills for managing unintended effects and scaling up impact.

Behavior as a Building Block of Social Change

There’s no social change without behavior change. While attitudes profoundly shape our thoughts, feelings, and intentions, only behaviors can translate those internal shifts into real-world impact. Yet research shows that attitude change doesn’t always lead to behavior change—especially when social norms, systemic barriers, or privilege get in the way. That’s why tracking behavior matters more than measuring sentiment alone.

We recommend that bridgebuilding evaluations include a focus on observable actions—what participants actually do differently as a result of their experience. This is especially important because the intangible nature of attitude change data can make it challenging to credibly analyze and interpret, particularly if it stands alone without reference to other types of data. On the other hand, behavior data and attitude data together make for a stronger package of evidence.

One behavior-focused evaluation approach we’ve found effective is Outcome Harvesting, which was developed by Ricardo Wilson-Grau. Rather than assessing only pre-defined metrics, Outcome Harvesting identifies real-world behavior changes—intended or unintended—and traces how the program contributed to them. This makes it especially useful in the complex and unpredictable civic environment of today’s United States. Michelle Garred’s firm, Ripple Peace Research & Consulting, has adapted Outcome Harvesting to include shifts in attitude and explore their relationship to behaviors, which matters greatly in bridgebuilding.

Contact Theory: Important, But Not Infallible

Contact theory, first developed by Gordon Allport in the 1950s, proposes that positive interactions between members of different identity groups can reduce prejudice. This idea remains foundational to many bridgebuilding organizations. The popular programs informed by contact theory include “light-touch bridgebuilding”—interventions that aim to improve attitudes across differences (often through brief or one-off dialogues), without seeking specific changes in action. These efforts are necessary as effective tools for reducing bias and polarization and increasing social trust—but cannot do all of the work to repair a tattered social fabric.

Comprehensive research compiled by Pettigrew and Tropp (2013) affirms that contact is typically effective—but it works best under certain conditions:

- Equal status among participants

- Shared goals

- Intergroup cooperation

- Institutional support

- Repeated and sustained interaction

When these conditions aren’t met, contact can fail—or even backfire. In the U.S. context, where there are major disparities in power or privilege, disadvantaged participants may feel dismissed or harmed by the experience, leading to a negative contact experience. Advantaged participants may leave feeling good but unchanged in action, contributing to what researchers call the principle-implementation gap ( Dixon, Durrheim, and Thomae, 2017).

In some cases, “single-identity contact”—where all participants are encouraged to see themselves through the lens of one shared identity—can even reduce disadvantaged groups’ engagement in collective action. This is because emphasizing sameness can mask structural inequities and discourage people from addressing them. In contrast, “dual-identity contact” encourages a shared identity while maintaining subgroup identities—and research shows it’s more likely to produce behavior change and a commitment to equity ( Glasford & Dovidio, 2011; Banfield & Dovidio, 2013).

In short: bridgebuilding in the U.S. should be designed with a clear eye toward power dynamics and evaluated with tools that measure impact beyond sentiment.

Tools for Managing Unintended Consequences and Scaling Impact

Bridgebuilding is not alone in facing unintended consequences and in being necessary yet insufficient to transform society on its own. The same is true of every social impact intervention, and there are strategy and design tools available to help us. Here we recommend two international tools created by CDA Collaborative Learning.

To address unintended effects, Do No Harm ( DNH) helps programs analyze and modify how their work interacts with “Dividers” (factors that drive groups apart) and “Connectors” (factors that bring them together). The aim is to avoid inadvertently exacerbating Dividers or undermining Connectors while actively working toward improved relationships. DNH promotes adaptive design, helping practitioners prevent or mitigate harm and amplify constructive effects.

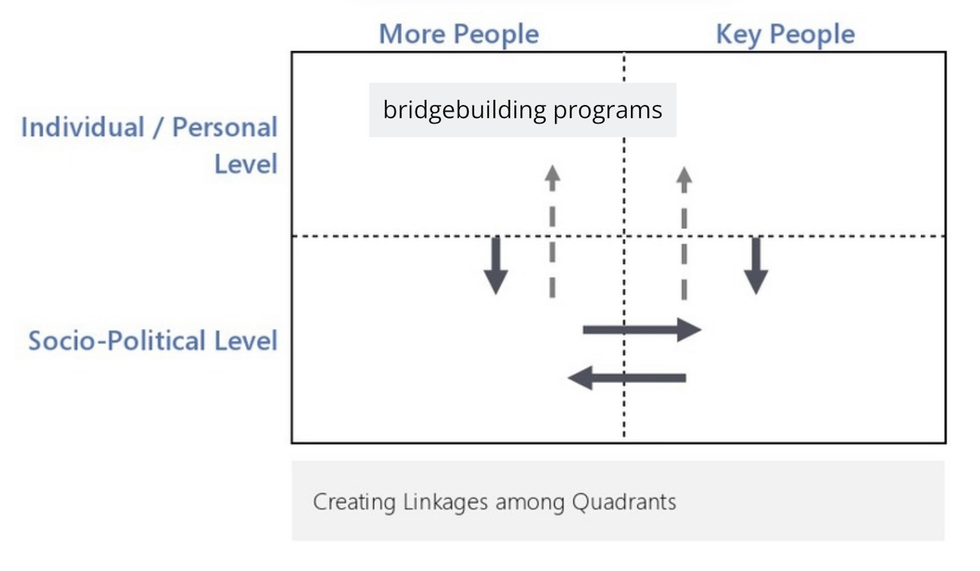

To grapple with the reality of being necessary but not sufficient, we turn to another CDA tool: the Reflecting on Peace Practice (RPP) Matrix. The RPP Matrix, which explores how different types of programs can complement each other, is based on two critical questions:

- Does the program aim to create change at the individual/personal level or the broader socio-political level?

- Does it engage “more people” (the general public) or “key people” (gatekeepers and decision-makers)?

Arranging those two dimensions in rows and columns forms a four-quadrant matrix (adapted from Reflecting on Peace Practice (RPP) Basics. CDA, 2016, p.41).

Most bridgebuilding programs fall into the “ personal change for more people ” quadrant. That’s not a flaw—but it is a limitation. Research from the RPP project shows that no single quadrant is sufficient on its own to drive systemic impact. What’s needed is either strategic expansion or partnerships that connect bridgebuilding to civic engagement, policy change, or institutional reform.

Initiatives like the Needham Resilience Network and Better Together America show how these connections can be built. They bring bridging work into community problem-solving, democratic deliberation, and local coalition-building—amplifying its reach and effectiveness.

A Role for Funders

We have suggested here that bridgebuilding alone will not suffice to repair the American social fabric—but we do believe that bridgebuilding makes a vital contribution to pro-democracy efforts. To best support this work, funders can:

- Fund robust evaluations that include a focus on behavior change

- Support partnerships that link bridgebuilding to broader social transformation and political reform

- Encourage use of evidence-based tools like DNH and the RPP Matrix

If funders and bridgers integrate these considerations, we believe this will strengthen bridgebuilding’s important contribution to our essential civic infrastructure: trust, empathy, and willingness to act in pro-social ways for the common good.

This article is an abridgment of a three-part series of blogs posted on the Cohesion Strategy and Ripple Peace websites.

Allison K. Ralph is a Senior Research Fellow at Kaufman Interfaith Institute at Grand Valley State University and the principal of Cohesion Strategy LLC.

Michelle Garred is the Founder and Principal at Ripple Peace Research & Consulting LLC.