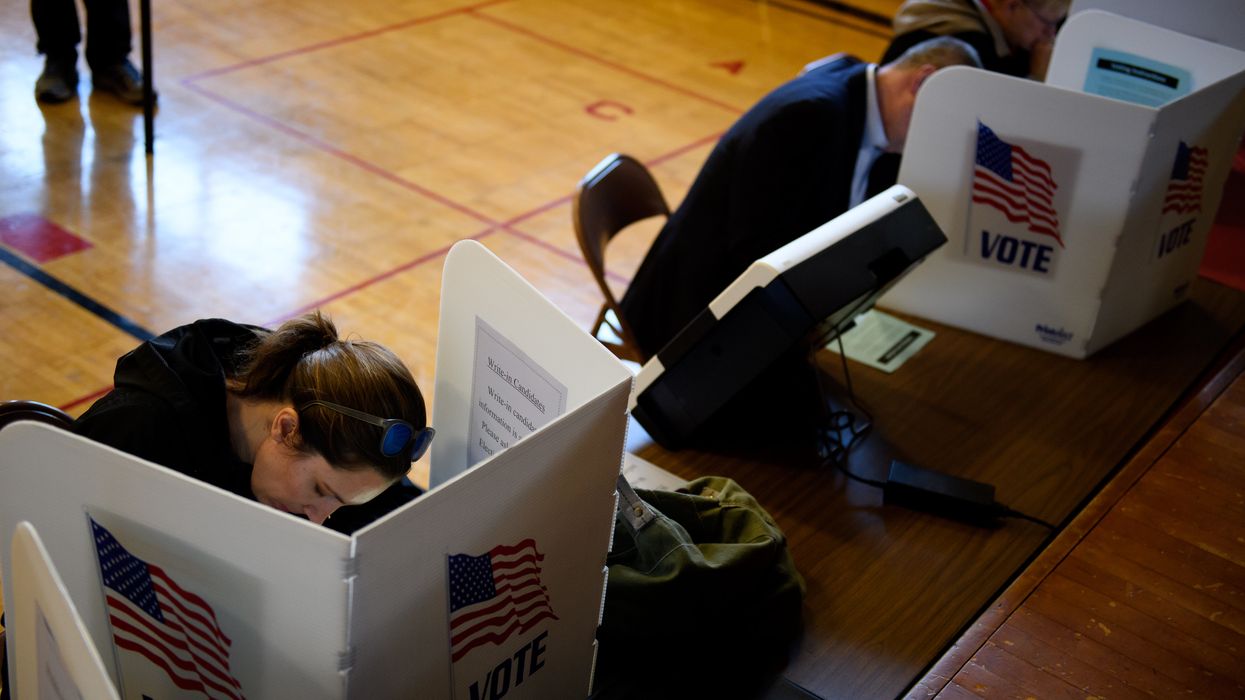

For Black Americans, the polling station has long been a militarized space, "guarded" by the violence and intimidation of white supremacists. After the Civil War when freemen began amassing political power in state legislatures, whites used murder, rape, lynching and other forms of violence to discourage Black voting.

Conservatives are organizing another network of vote intimidators for the November election, which could disenfranchise millions of voters of color. As registration deadlines approach, states must address the potential for intimidation at polling sites to ensure a free, fair and non-discriminatory election.

Voter intimidation — intimidating or threatening someone with the goal of interfering with their right to vote — is illegal under federal law. But it wasn't always so. Whites — both vigilantes and legal authorities — used intimidation to block access to the voting booth. When Union troops began to withdraw from the South after Reconstruction, groups like the Ku Klux Klan and the Knights of the White Camellia used racial terrorism to discourage freemen and their white allies from voting. During the civil rights movement, segregationists like Bull Conner likewise assaulted Black demonstrators calling for integration and voting rights with dogs and fire hoses.

Throughout U.S. history, voter intimidation not only disenfranchised Black Americans, but also cost those who sought the right to vote their very lives.

In 2020, we must also ring the alarm around the coordinated effort to intimidate Black and Latino voters. Conservatives have invested $20 million to mobilize 50,000 volunteers to "guard the vote" during early voting and on Election Day. President Trump has even called for stationing armed guards at the polls while stoking widely debunked myths of in-person voter fraud. It is critical that Black and Latino voters who led national protests against state violence in 2020 are able to cast ballots free from hostility.

What can we do to ensure they can access the polls safely?

One, we must educate them so they can identify and appropriately respond to any voter intimidation they witness or experience. If someone aggressively questions you, harasses you or challenges your eligibility to vote outside of the polls, document and report the incident to an election official at the site. Request any person engaging in this behavior be removed from the polling place. Call the national Election Protection hotline (1-866-OUR-VOTE), which is staffed by voting rights lawyers who can help you in real time.

Second, advocates should work with election officials to limit the role of police at the polls. Election officials should also restrict firearms at polling sites. Police at the polls may intimidate voters who are justice-involved, while the recent killings in Kenosha, Wis., highlight the danger when deadly weapons are brought to contested spaces.

To be sure, it is important police are quickly dispatched to polling locations in an emergency. But state and local officials should recruit enough poll workers to manage social distancing in long lines, control crowd flow and provide assistance to voters with disabilities or language access needs. These roles are inappropriate for law enforcement.

Finally, we must restore the Voting Rights Act. Prior to the Supreme Court's weakening of this law in the Shelby v. Holder case, federal employees would monitor elections in states with a history of racial discrimination. In 2020, it is clear that the Department of Justice won't be saving Black voters from voter intimidation. It is up to the organizers, advocates, and grassroots leaders to continue the fight.

Gilda Daniels is litigation director of the Advancement Project and the former deputy chief in the Voting Section of the Department of Justice's Civil Rights Division. Read more from The Fulcrum's Election Dissection blog or see our full list of contributors.