Serving in Congress during the implementation of President Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act, Republicans embraced the position of “repeal and replace.” Repeal the ACA, but replace it with what? The debate is front-and-center again, though the ground has shifted some. There is more support for the ACA. Even some Republicans are looking to temporarily extend COVID-era subsidies for ACA health plans. Other Republicans want Health Savings Accounts, so more money goes to individuals instead of insurance companies. Democratic leadership seeks an approach temporarily extending the expanded premium subsidies, during which the entire approach to health care can be rethought.

The late economist Martin Feldstein had the fix: Martin Feldstein proposed a voucher system in which everyone could purchase a health insurance plan covering health care expenses exceeding 15% of their income. This could be combined with HSAs if they prove popular with the public.

The variable prices for medical care across common geographic areas help illustrate that greater cost-consciousness in health care could have an impact. “In a well-functioning competitive market, prices for the same service will not vary widely within a given place,” the Brookings Institute summed it up. Brookings offers two examples: “Estimates from the Health Care Cost Institute show that the price for a blood test ranges from $22 (10th percentile) to $37 (90th percentile) in Baltimore, Maryland, but in El Paso, Texas, the same range is $144 to $952. For a C-section delivery, prices vary widely both across and within markets: the 10th to 90th percentile range is 9.3 times larger in the San Francisco, California, metro area than in the Knoxville, Tennessee, metropolitan area. Getting a well-functioning competitive marketplace will drive prices down while still incentivizing quality care.

So, rethinking the health care system has value, but any debate should also consider whether a little more free-market would be beneficial in our mixed-economy health care system. The advantage of the Feldstein proposal rests here: There would be greater price sensitivity in the health care sector, a sensitivity that encourages greater efficiency and cost-lowering, competitive innovation.

Physicians, hospitals, and other health care facilities would gain reputations as being more expensive or less expensive. A doctor might be willing to provide discounts to patients in need, especially if we also generously fund non-profit community health centers for the medically needy. There may be more conversations about the frequency of checkups or the duration of a long-term stay. Fewer tests that are not truly necessary. Lower administrative expenses. Less headaches with insurance in general.

If someone buys insurance to work in conjunction with Feldstein’s proposal, premiums would be lower due to several factors. The insurance policy would not have to cover as much. There would be greater predictability for each insurer about how much risk they are taking on with any one policyholder, and that predictability would encourage more competition within the consumer insurance market.

There was an interim version of the Affordable Care Act from 2014 to 2016, as the bill’s health insurance exchanges were coming into being. Specifically, the Transitional Reinsurance Program in the ACA was a government-provided reinsurance policy that supported insurance plans in the individual market by covering a portion of a plan’s costs, starting in 2014 at 100% of costs between $45,000 and $250,000. The cost of doing so was financed through a fee on plans in both the individual and group marketplaces. Something which reduced health insurance premiums for the individual market by 10-14%. That is the real-world experience of the benefit of reducing risk to any one insurance plan.

Income-related cost sharing, as proposed by Feldstein, could reduce health premiums even further. By one estimate, a whopping 22-34% of overall health expenses. All without jeopardizing patient care.

Feldstein’s article and its ideas never became a significant part of the health care debate. Six months after the publication of the Feldstein proposal, the Affordable Care Act was signed into law by President Obama. After the transition period, the bill created only a complicated set of taxes and subsidies, a kind of Rube Goldberg device – different pieces creating incentives for different directions, not certain to come together in the best way for the American people. The complexity of today's health care system under ACA continues to collide with the complexity of how we pay - or sometimes don't pay - for it. We should have a health care system as good as our current system, and then some. A health care system that can heal itself with the right incentives. All of which means not becoming Canada or Great Britain with their longer wait times; rather, creating a unique American system along the lines of the Feldstein model.

A couple more years of debate over health care could perhaps lead to this bolder approach if part of the political culture embraces it. Even if not, debate over cost-consciousness must occur. Taking care of the sick is a moral imperative for government; red tape, bureaucracy, high health care costs, and narrow provider networks are not.

Scott Miller is a graduate of Widener School of Law, a former chief of staff in Congress, and the author of 'Christianity & Your Neighbor's Liberty.

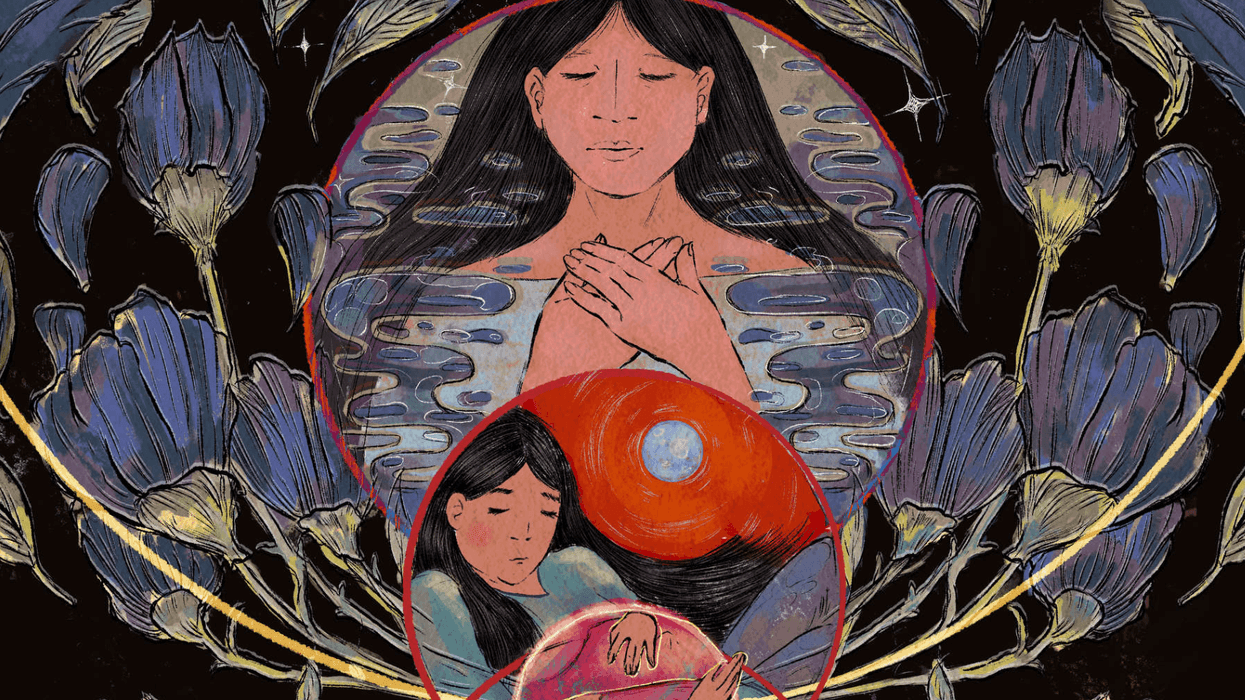

Native American women face higher rates of death than other demographics. (Oona Zenda/KFF Health News)

Native American women face higher rates of death than other demographics. (Oona Zenda/KFF Health News)