Healthcare in 2025 was consumed by chaos, conflict and relentless drama. Yet despite unprecedented political turmoil, cultural division and major technological breakthroughs, there was little meaningful improvement in how care is paid for or delivered.

That outcome was not surprising. American medicine is extraordinarily resistant to change. In most years, even when problems are obvious and widely acknowledged, the safest bet is that the care patients experience in January will look much the same in December.

But when meaningful change does occur, it is usually because motivated leaders find themselves in rare political and economic conditions. Think of President Barack Obama in 2009, with unified Democratic control of Congress and widespread voter frustration over healthcare costs and coverage. By contrast, President Bill Clinton’s ambitious reform effort collapsed in 1993 when it collided with powerful industry opposition and a divided political environment.

If most years prove stagnant, why should anyone expect 2026 to be different? In a word: pressure.

Congress, the president, drug manufacturers and insurers are all confronting forces that make inaction increasingly risky. Three external pressures will drive change:

1. Politicians Face Midterm Pressures

For Republicans broadly, and for President Trump personally, the 2026 midterm elections present significant political risk. Even a modest shift in “purple” districts could flip control of the House, reshaping committee leadership and reviving the prospect of Trump’s impeachment.

The “Big Beautiful Bill” passed by Congress in mid-2025 locked in permanent tax cuts with a multitrillion-dollar price tag, narrowing the universe of spending categories large enough to materially reduce the deficit.

With healthcare accounting for nearly 30% of the federal budget (and other categories such as Social Security and defense politically untouchable), medical spending became one of the few remaining fiscal levers. But pulling it also handed Democrats a potent midterm weapon.

The shutdown compounded the problem. By linking government dysfunction to healthcare funding and coverage uncertainty, Democrats spotlighted rising medical costs as a symbol of incumbent political failure.

As healthcare economics worsen in 2026, the pressure will intensify. Premium increases will outpace wage growth. Deductibles will remain high. Tens of millions of Americans face potential Medicaid coverage losses, while 20 million more will see sharply higher exchange premiums.

The likeliest response to pressure: Fearful of losing the House, Trump and congressional Republicans are likely to pursue targeted, high-visibility actions designed to appease voters.

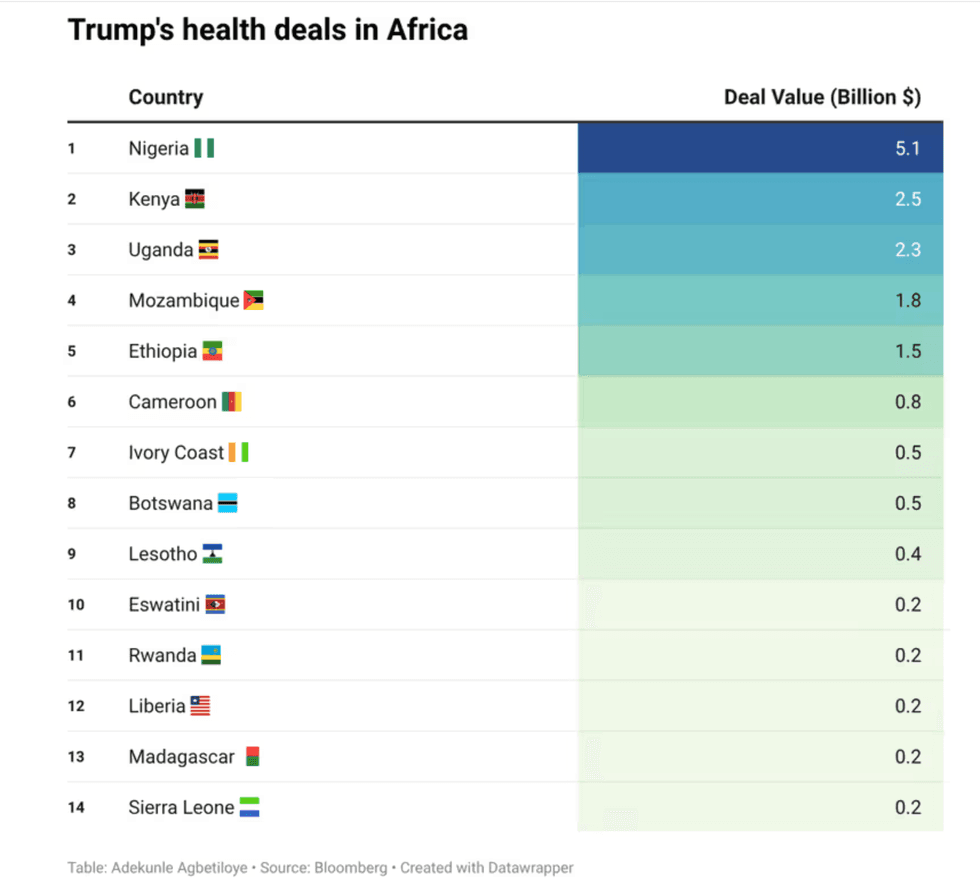

Drug pricing offers a clear example. In November, the White House announced agreements with nine large pharmaceutical companies to lower prices on certain medications under a “most-favored-nation” framework. However, those deals won’t materially lower prices because they apply only to Medicaid and selected drugs, leaving most privately insured patients exposed to persistently high costs.

Other options Congress and the president are likely to pursue include a short-term extension of exchange subsidies paired with familiar proposals such as expanded health savings accounts, “catastrophic” plans and lower limits on premium support.

2. Drugmakers Face Political Pressures

For decades, the pharmaceutical industry has occupied a uniquely protected position in the U.S. economy. Long patent exclusivities, limited competition from generics and biosimilars and sustained lobbying success have shielded it from price regulation. As a result, pharmaceuticals remain among the fastest growing and most profitable U.S. sectors.

Americans currently pay two to four times more for prescription drugs than patients in other wealthy nations, and roughly one in three prescriptions goes unfilled because of cost. Affordability has become a crisis for employers and voters.

The likeliest response to pressure: Given the growing political pressure, drugmakers face a strategic choice. One path is familiar: resist change through lobbying, campaign contributions and legal challenges. The other is more adaptive: accept lower margins on some products in exchange for higher volumes and reduced political risk.

Based on the recent agreements that brought 14 of the 17 largest drugmakers into voluntary pricing arrangements with the administration, most are likely to continue to follow the second path.

By shielding their most profitable products while conceding selectively on pricing, manufacturers can reduce political pressure without materially sacrificing profitability.

3. Insurers Are Trapped In An Unsustainable Business Model

In 2026, employer-sponsored premiums are projected to rise at roughly twice the rate of inflation. The annual cost of coverage for a family of four will be $27,000, with employees paying roughly one-quarter of that total out of pocket.

Patients already delay or forgo care because of cost. Meanwhile, medical bills remain the leading contributor to personal bankruptcy in the United States.

Insurers, who have no control over how medicine is practiced, have relied on tighter prior-authorization requirements, narrower networks and higher rates of claims denial. While these tactics can suppress short-term spending, they have fueled widespread backlash from patients, physicians, employers and lawmakers.

In effect, insurers are being squeezed from both sides: rising costs they cannot fully pass on and a public increasingly hostile to how those costs are managed.

The likeliest response to pressure: When premiums and out-of-pocket costs exceed what payers and patients can bear, the traditional insurance model begins to fracture.

That is where capitation re-enters the conversation. Under capitation, insurers make a fixed, per-patient payment to a physician group or health system to manage most or all care for a defined population. Providers assume responsibility for utilization, coordination and cost control. In return, they gain flexibility in care delivery and the opportunity to share in savings when prevention and chronic disease management succeed.

For insurers, the appeal is straightforward: capitation shifts financial risk downstream and reduces reliance on unpopular utilization controls. But moving from fee-for-service to capitation would require major structural change. As a result, insurers in 2026 are more likely to introduce pilot programs, partial risk arrangements and expanded use of generative AI rather than pursue wholesale transformation.

A new year carries the promise of change. Look for shifting political and economic climates to make 2026 a year of healthcare improvement, especially compared to 2025.

Robert Pearl, the author of “ChatGPT, MD,” teaches at both the Stanford University School of Medicine and the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He is a former CEO of The Permanente Medical Group.

Native American women face higher rates of death than other demographics. (Oona Zenda/KFF Health News)

Native American women face higher rates of death than other demographics. (Oona Zenda/KFF Health News)

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift