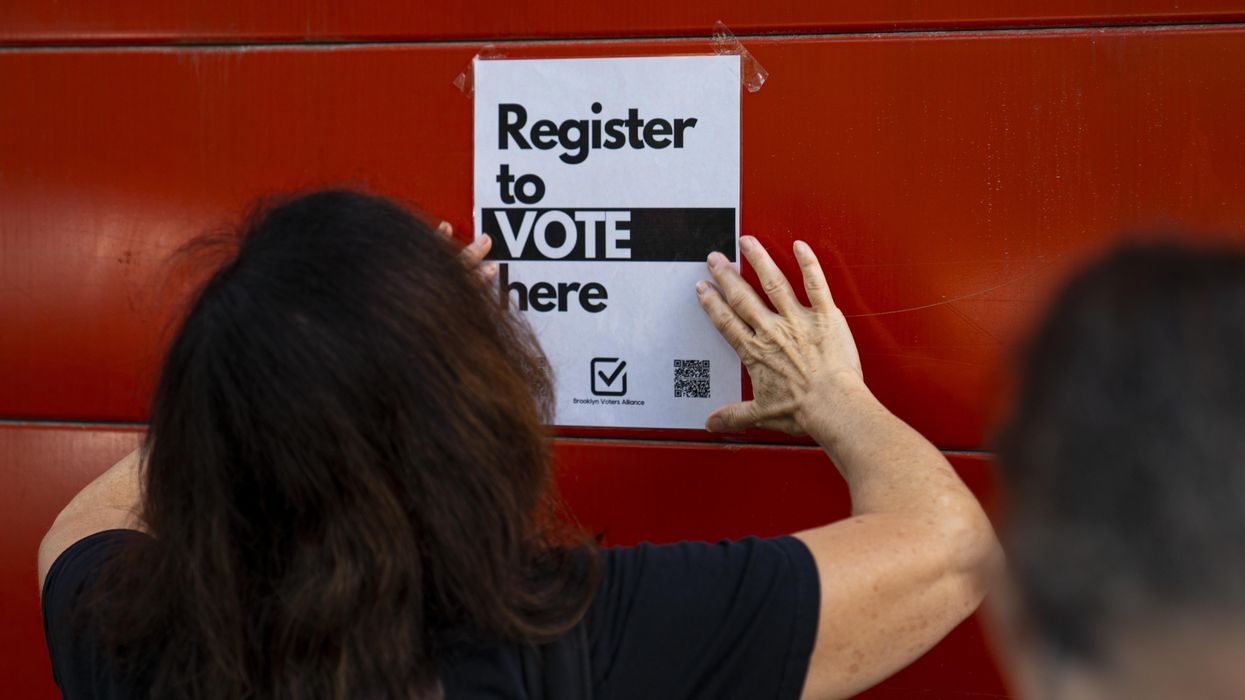

On National Voter Registration Day last September, activists, neighbors and community volunteers across the country took to the streets to help 1.5 million voters get registered in the span of just 24 hours, a historic feat in preparation for the 2020 election. But today, on this year's National Voter Registration Day, those same volunteers are being targeted by extreme, partisan anti-voting measures around the country.

Since 2012, National Voter Registration Day has mobilized thousands of volunteers to help fulfill the promise of our democracy: ensuring that all Americans have access to the ballot. While election officials work tirelessly to expand participation in our elections, many of them have too little funding and resources to reach potential voters, especially those in communities that have been historically underserved and disenfranchised.

Voter registration volunteers fill that gap. They expand the reach of election officials, building trust with their community members and encouraging them to participate in our elections. They regularly reach voters who are missed by government efforts by meeting them where they are, including at grocery stores, schools and community events. These efforts are a necessity for people with disabilities, young people, and Black and Latinx voters, who are up to twice as likely to register at voter registration drives than white voters.

Now, those very acts of civic engagement are being penalized in states across the country. Volunteers and community organizers in states like Texas, Florida and Kansas can face felony charges or hefty fines for helping voters register if they accidentally run afoul of needlessly cumbersome regulations that are often vague and may be enforced unpredictably.

These laws do nothing to strengthen voter registration; on the contrary, they are having immediate, debilitating impacts on efforts to sign up more voters. After Kansas made it a felony offense to give off the appearance of being an election official — a frighteningly ambiguous and subjective law — multiple groups, including the League of Women Voters, were forced to suspend their voter registration drives. As a result, fewer prospective voters will have the opportunity to get the voter registration assistance they need, shutting them out from the electoral process. These attacks on community-centered registration efforts are a severe threat to our democracy and a clear, partisan attempt to make it harder to vote. They must be stopped.

Laws penalizing essential, good-faith efforts to help voters register sow unnecessary distrust between volunteers and their neighbors, with the intent of restricting who gets to vote in our elections and without making elections any fairer.

Overturning extreme voter suppression laws and protecting the rights of the American people will require an all-hands-on-deck effort, including fighting these needless regulations in the courts. That's why my organization filed a lawsuit against Florida's bill SB 90 for requiring volunteers to provide misleading information to potential voters that could make them less likely to register and harder for community groups to build trust with those they help.

As election lawyers and voting rights advocates fight against the extreme, state-level restrictions to accessing the ballot box, the federal government needs to pass protections that remove unnecessary barriers to voter registration. The new Freedom to Vote Act introduced in Congress would make it easier for more people to register, including through same-day voter registration, thus freeing up more time and resources for election officials and community organizations to focus their outreach on communities that need it most.

Whatever their race, background or ZIP code, all eligible Americans deserve access to the ballot. Helping our neighbors and fellow citizens exercise their right to vote is a non-negotiable part of making that right a reality.

Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ranking member Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA) (R) questions witnesses during a hearing in the Russell Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill on February 10, 2026 in Washington, DC. The hearing explored the proposed $3.5 billion acquisition of Tegna Inc. by Nexstar Media Group, which would create the largest regional TV station operator in the United States. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ranking member Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA) (R) questions witnesses during a hearing in the Russell Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill on February 10, 2026 in Washington, DC. The hearing explored the proposed $3.5 billion acquisition of Tegna Inc. by Nexstar Media Group, which would create the largest regional TV station operator in the United States. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)