Zeiger is president of the Jack Miller Center.

One of my earliest impressions about the importance of citizenship was when I learned about how my great grandpa Ernest Zeiger went to the local city council in Puyallup, Wash., in the 1980s to stop the city from chopping down a giant black walnut tree in his neighborhood. It was a “centennial tree” planted in 1889, the year Washington became a state. Because Ernest and a few other citizens took a stand, that huge, marvelous tree still stands.

My great grandpa was my first example of what a recent report from More in Common terms a “civic role model,” but he was certainly not the last. Drawn as I was towards political life at a young age, I sought out role models wherever I could find them. I checked out biographies of presidents from my school library and, as a teenager, I paid attention to local officeholders and even volunteered on some of their campaigns. Later on, when I was elected to public office myself, I was blessed to have a little group of mentors — current and former officials I admired and who shared their lessons and advice.

The more I immersed myself in the life of my community during a dozen years in state and local public service, the more I came to look up to men and women who held no public title but whose daily lives were profound examples of civic commitment. These were people making a difference outside of politics, like Krista Linden, who is building a dynamic social enterprise serving at-risk moms, or like Bill Bowers, who started a project to get people of faith involved in volunteer service, or like the mighty group of rails-to-trails advocates who have relentlessly pursued their vision for a recreational trail over many years.

They, and many others I encountered, joined my growing roster of civic role models. And though they lacked the fame and celebrity of presidential candidates, TV commentators and social media influencers, they were making an incredible difference in civic life every day.

More in Common’s recent report reminds us of the essential part that civic role models play in American society. For our shared experiment in self-government to work, we need citizens who set the example for their fellow Americans — especially for young people. In a self-governing republic, citizens are meant to model what it means to live a good life for each other.

One of More in Common’s most important findings shows that if respondents had a civic role model, it was likely to be a family member. Engaged parents pass along their good habits to their children, who in turn develop an interest in citizenship. They also play an important role in teaching their children about the country. President Ronald Reagan said it well in his farewell address in 1989: “All great change in America begins at the dinner table. So, tomorrow night in the kitchen I hope the talking begins. And children, if your parents haven't been teaching you what it means to be an American, let 'em know and nail 'em on it. That would be a very American thing to do.”

Sadly, according to the More in Common study, most American adults who were surveyed say that they do not have a civic role model. “No one to look up to in that area,” said one survey respondent.

So how can we encourage, support and celebrate America’s civic role models?

More in Common makes three principal recommendations “for building more civically engaged communities.” First, it says we need to “improve storytelling.” Specifically, More in Common suggests telling more stories about civic role models working to improve their communities. The 250th anniversary of American independence is a particularly powerful moment to do this — America 250 and other civic organizations have an incredible opportunity to tell the inspiring stories of civic role models. The America 250 Commission has already assembled a wonderful collection of “ America’s Stories,” featuring the voices of diverse civic role models from all over the country.

Next, More in Common recommends “building more collective settings.” It is important to cultivate spaces where people can solve problems facing their communities. Sociologists such as Robert Nisbet and Robert Putnam have long warned about the decline of civic associations. Ray Oldenburg has written eloquently on the disappearance of “third places,” between home and work, where citizens can meet together. It is in such places that we are likely to come into contact with civic role models, and where we can each do our part to make a difference and set the example for the next generation. Especially after the pandemic, we need to deliberately work for the restoration of these spaces for shared participation.

Participation is the essence of American citizenship, and it encompasses many parts of our civic life. “The word participation has been used in recent decades chiefly to denote political involvement, as in the phrase participatory democracy,” wrote John W. Gardner. “The voluntary sector of our society offers endless opportunities for such involvement.” Every time someone gets involved in their community, we might say, they offer themselves as a role model to a friend, a family member or a neighbor.

In their book “ Gardens of Democracy,” Eric Liu and Nick Hanauer made a point similar to Gardner’s: “Citizenship isn’t just voting. Nor is it just Good Samaritanism. A 21st-century perspective forces us to acknowledge that citizenship is, quite simply, the work of being in public. It encompasses behaviors like courtesy and civility, the ‘etiquette of freedom,’ to use poet Gary Snyder’s phrase. It encompasses small acts like teaching your children to be honest in their dealing with others. It includes serving on community councils and as soccer coaches. It means leaving a place better than you found it. It means helping others during hard times and being able to ask for help. It means resisting the temptation to call a problem someone else’s.”

It's time we recovered a broader view of civic engagement, and civic role models can lead the way in this recovery.

Finally, More in Common calls for greater investment in civic education. Americans need to know about the national role models who envisioned our experiment in self-government and shaped our institutions — the framers of the Constitution who set forth a model of deliberation, the statesmen and women who navigated great difficulties and pursued needed reforms, the visionaries and pioneers, community-builders and philanthropists who went before us and shaped the nation we inhabit. And we need to be introduced to contemporary civic role models who are doing their part closer to home, and who we can aspire to emulate.

Citizenship is hard work. It requires us to invest scarce time and resources, even when it seems inconvenient. But the return on that investment — a thriving, free, self-governing society — is more than worth that price. As the More in Common survey reveals, there is much work to be done. When it comes to saving America’s civic life, it’s all hands on deck.

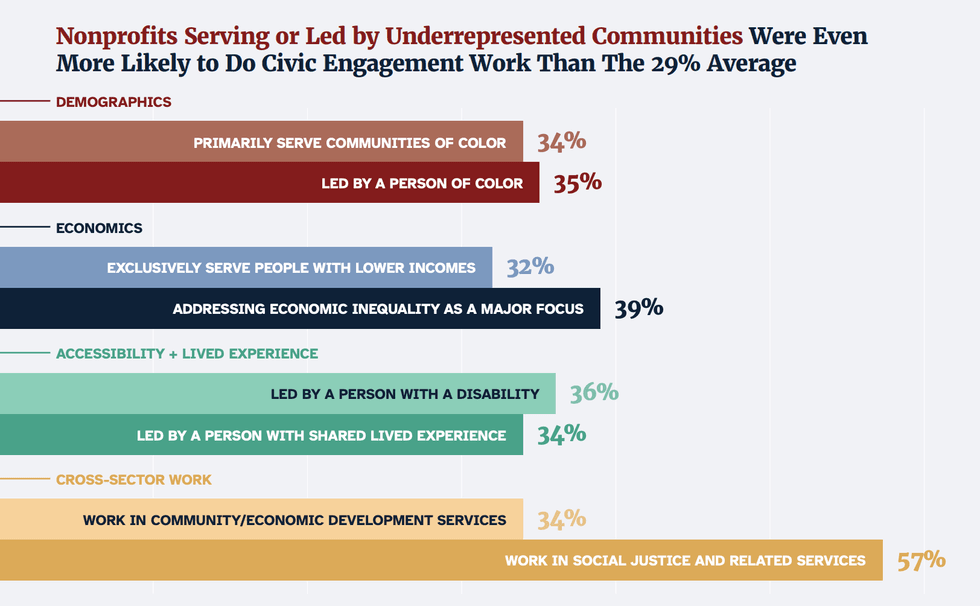

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

"On the Frontlines of Democracy" by Nonprofit Vote,

Trump & Hegseth gave Mark Kelly a huge 2028 gift